Edward J. Kelly

Edward J. Kelly

Abstract

Despite the intuitive feel of constructive-developmental theory (Kegan, 1980; 1994; McCauley et al., 2006; Torbert, 1987, 1994, 2004), it has had very little impact on the mainstream literature in leadership development. One reason for this maybe a lack of exemplars to tell the developmental story. The findings from this research may help to change that. My study of Warren Buffett concludes that Buffett’s development has gone through ‘seven transformations in meaning-making’ and that these transformations have impacted his success as a leader. It is no exaggeration to say that without his development Buffett could not have created the current leadership culture at Berkshire, which is seen by many, including Buffett, as the key to the future sustainability of Berkshire. What is relevant from a developmental perspective however is that the patterns in Buffett’s development can now be explained by a theory of development that has nothing to do with Buffett. In other words Buffett’s development is not unique to Buffett. This has interesting consequences for the rest of us. If Buffett’s development can be explained by an existing theory of development, then what does that theory have to say about how we may develop as well? That question is the focus of this article.

Introduction

This is the second of three articles in which I summarise my developmental research on Warren Buffett. In the first article I dealt with the question, ‘what was the research about, what methods of inquiry were used and what were the results’? In other words what were the objective third-person findings of the research? In this second article I want to consider, from a second-person perspective, ‘what can we learn from the research and what does it cause us to do, if anything’? The third article will then address my first-person reflections on the research, ‘what did I think and feel about the research and what impact did it have on me’?

As described in the first article, the subject of my research was ‘development’ and the object of my research was thirty-two examples from Warren Buffett’s life. I choose Warren Buffett because he was of interest to me. I had followed him for years, taught courses on his investment approach (called “Bend it like Buffett”), had become a Berkshire shareholder and had attended a number of Berkshire AGM’s. Over a ten-year period I became immersed in the Buffett and Berkshire culture. Thus, when I was ready to start the study I felt I knew something about Buffett and I had built up a community of others around me who would help keep me on track.

To move forward with the study I had to create a new developmental lens or method to analyse the ‘developmental depth’ in Buffett’s actions. This was inspired by constructive-developmental theory (Cook-Greuter, 1999; 2000; 2005; Kegan, 1980, 1982; 1994; Torbert, 1976, 1987, 1991, 1992; 1994; 2004; McCauley et al., 2006) and consisted of applying four developmental variables, ‘perspectives, timeframe, feedback and use of power’ to analyse the ‘action’ in each example. This framework was ‘consistently’ applied across the thirty-two examples. The four developmental depth questions were;

- What perspective(s) was he operating from in this action?

- What timeframe was he aware of?

- How open was he to feedback from himself, others and the world, and

- How did he use his power in action?

In order that this developmental framework provides a consistent reading of the patterns of development over time, it has to be ‘content free’ and ‘context neutral’. It was clear however that Buffett’s development wasn’t the only factor influencing his actions and in some cases it wasn’t even the most important factor. Hence I also asked a number of other ‘non-developmental’ questions such as, ‘what other first-, second- and third-person factors were influencing his actions in each example’? (Torbert & Ass., 2004; Wilber, 2002; 2006). His developmental depth was nonetheless relatively important in nearly all examples and particularly important in respect of his changing approach to leadership.

Buffett’s logical mathematical intelligence and rational temperament (his pre-dispositions) coupled with his early adoption of Ben Graham’s investment method go along way to explaining his early success as an investor, but something else is required to explain his later success as a leader. What became clear from this study was that that ‘something else’ was Buffett’s development. This is the story less told about Buffett, how the development in his character influenced his success as a leader. I will go further later and show why I think that without Buffett’s development he would have been unable to create the kind of leadership culture we see at Berkshire to-day and which is now considered so important to the future sustainability of Berkshire.

That Buffett has developed over his long career and that his development has impacted his leadership was not a new insight. The many biographies of Buffett’s life had already described his unique development (Kilpatrick, 2004; Lowenstein, 1997; O’Loughlin, 2002; Schroeder, 2008). What was new about my research however was that Buffett’s development could now be understood from the perspective of an existing theory of development that had nothing to do with Buffett. What became clear from the study was that Buffett’s development matched the description of development at each of the action-logic stages of development (Torbert, 1976, 1987, 1991, 2004). Like many others before him, his development followed the predicted order of development already described by adult developmental theory. It seems his development was not unique to him after all.

This raises interesting questions that are addressed in this article. Firstly, if Buffett’s development can be understood from the perspective of an existing theory of development, then what does that theory have to say about how others may develop as well? Secondly, if Buffett’s development is a necessary precursor to his success as a leader, what does this say about the importance of development to the field of leadership development? Both questions are considered from the perspective of Buffett’s use of power, how it changed and what impact it had on the leadership culture at Berkshire.

Seven Transformations in Leadership

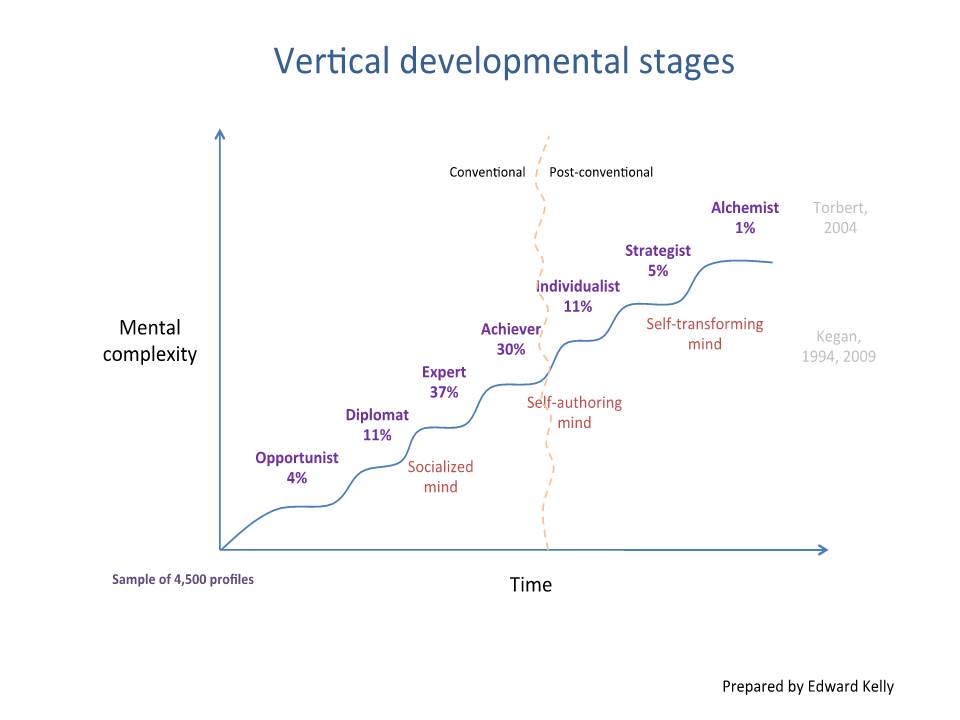

It was evident from my study that Buffett had gone through “Seven Transformations in his meaning-making” (Rooke & Torbert, 2005). By transformation here I mean a fundamental change is his overall meaning-making as understood by adult developmental theory and in particular by Torbert’s developmental action-logics. Each such transformation is felt like a ‘making the mind anew’ and is experienced as a complete upgrade in the individual’s internal organising system. With each new transformation the individual’s whole field of attention; their thinking, feeling and doing, change. In Torbert’s model these developmental stages are called action-logics and are named; Opportunist, Diplomat, Expert, Achiever, Individualist, Strategist and Alchemist with the last five action-logics (Expert, Achiever, Individualist, Strategist and Alchemist) being the adult stages.

Of the thirty-two examples in my study, two examples matched at the Opportunist action-logic (examples 1 and 2), three examples at the Diplomat action-logic (examples 3, 6 and 22), eleven examples at the Expert action-logic (examples 4, 5, 7, 8, 9&10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 18), five examples at the Achiever action-logic (examples 15, 16, 17, 19 and 21), four examples at the Individualist action-logic (examples 20, 23, 28 and 29), five at the Strategist action-logic (examples 24, 25, 26, 27 and 30) and two at the Alchemist action-logic (examples 31 and 32). From this we can say that Buffett has gone through seven transformations in his meaning-making. Interestingly and perhaps not surprisingly, these transformations are correlated with Buffett’s age. It seems that at least in Buffett’s case, that as he has gotten older he has also gotten wiser.

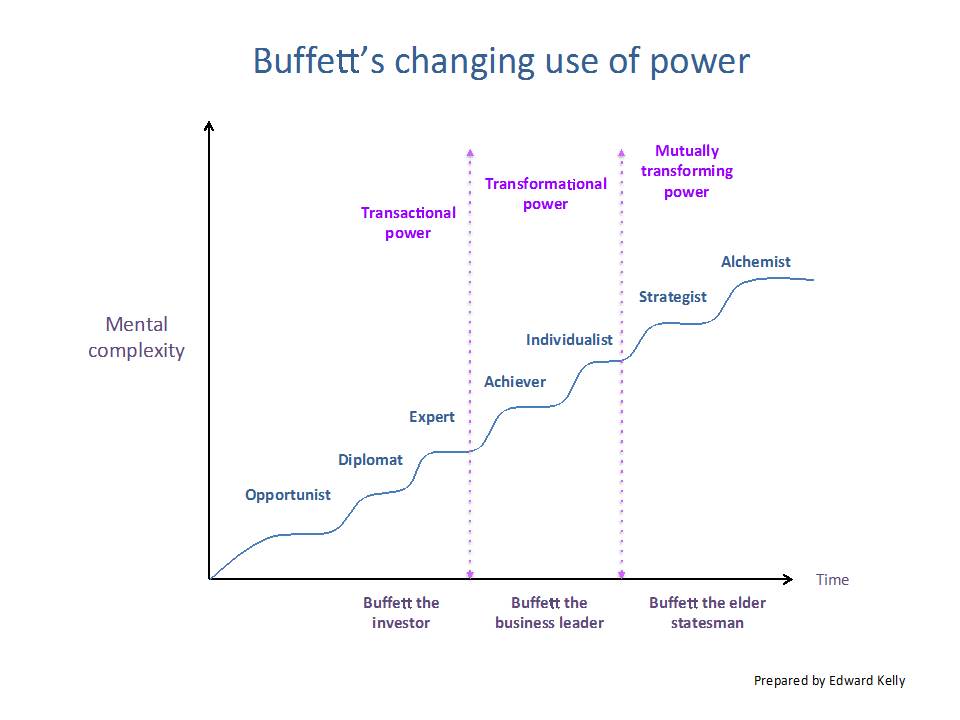

In order to give you a flavour of these different action-logics, there follows a short description of how the ‘perspectives, timeframe, openness to feedback and use of power’ change with each action-logic (see also figure 1). This in turn is followed with three examples which highlight Buffett’s changing ‘use of power’ from ‘transactional, to transformational to mutually transforming’ power. This is central to understanding Buffett’s changing approach to leadership.

- Opportunist. At the Opportunist action-logic, the self is subject to its own will and desire (a limited first-person perspective). There is no conscious awareness of time. Time-frame is limited to weeks or months. There is no openness to feedback and feedback that is given is treated as an attack or a threat. Blame is externalised. Use of power is based on the moral of authority “might is right”. Power is exercised coercively and unilaterally and is motivated by one’s own needs.

- Diplomat. At the Diplomat action-logic the self’s centre-of-gravity shifts to a reliance on the perspective of others; peer group, family, culture or society (a second-person perspective). There is no change in any conscious awareness of time although time-frame may extend from months to a year. There is still no openness to feedback and feedback that is given is felt as a criticism and as disapproval. Diplomatic power is based on the morality of association, thy will not mine and where social norms take precedence over personal needs.

- Expert. At the Expert action-logic the self is immersed in the logic of its own beliefs (a primarily third-person perspective). There is a beginning self awareness of durational time, 1-2 years. There is also an openness to feedback but this tends to be limited to experts in the field of their primary interest. The expert’s use of power is based on the morality of principle, “the method or process is right” and thus their craft-logic or favourite logic rules over social norms and personal needs.

- Achiever. At the Achiever action-logic the self begins to operate from an expanded third-person perspective. This allows for a more inclusive approach. The self is now consciously thinking in durational time (past to future). Timeframe may extend out 2-5 years, past and future. It also adopts a pragmatic openness to feedback provided it can serve the overall goal. This may be experienced as a form of single-loop learning that can result in a first-order change in behaviour. Power is now based on the morality of authority and principle. The overall system effectiveness and goals are considered more important than any one system. This is a more ‘independent’ and systematic use of power as opposed to the more ‘dependent’ type of power at the Opportunist (on personal needs) at the Diplomat (on the will of others) and at the Expert ( on whatever the method says).

- Individualist. At the Individualist action-logic there is a noticeable separation as the self begins to explore the subjectivity behind objectivity. For some this can be experienced as a real existential crisis. In the process the self sees the relative and constructed nature of reality including one’s own (a fourth-person perspective). As the self turns inwards it has a beginning awareness of present time as well. Timeframe also expands out 5-10 years. The self now welcomes feedback as being necessary to self-knowledge and to uncover hidden aspects of own behaviour. Use of power is now balanced with earlier forms of Coercive, Diplomatic, Logistical and Systematic power. The self is drawn to adapt, explore and create new rules were appropriate. No one approach or use of power is preferred. Relativism rules Systematic effectiveness of any single system (independent)

- Strategist. At the Strategist action-logic the self returns reinvigorated with a new ‘post-objective-synthetic theory’ (an expanded fourth-person perspective). The self can now add an awareness of present time to thinking in durational time, past to future. Timeframe may also extend over 10-20 years. The self also invites feedback for self-actualisation. Reflecting a kind of double-loop feedback which may lead to a second-order change in over all strategy or action-logic as well as behaviour. Power is directed outwards towards optimizing interaction of people and systems. Concerned with reframing and reinterpreting situations so that decisions support overall principle. Most valuable principles rule the relativism of any one system (inter-independent).

- Alchemist. At the Alchemist action-logic the self begins to see the limitations of all representational maps, including maps of development such as this one. The construction of the ego and its influences over one’s life becomes more transparent and is seen as a limitation to further growth (a fifth-nth-person perspective). ‘Knowing’ is experienced in the more direct sense of experience. The self can now also experience a three dimensional awareness of time (durational time, non-durational present time and seeing oneself living in the present among others intentionally influencing one anothers’ futures). Time-frame may extend over 100 years. The self views feedback as a natural part of living systems. Open to a kind of Triple-loop feedback which can lead to a third-order change in overall goal or mission (as well as behaviour and strategy) and which changes and dissolves into a sense of connectedness to a ‘whole’, (Starr & Torbert, 2005). The self may also practice a type of mutually-transforming power which looks to create transformational opportunities for self and others. Deep processes and inter-systemic evolution rule earlier principles (inter-independent).

Figure 1. Constructive developmental theory

Buffett’s Changing Use of Power

In the earlier examples from Buffett’s life, i.e., those that match with the Opportunist, Diplomat, Expert and Achiever action-logics, Buffett exercises a kind of ‘unilateral power’ which ensures that he gets what he wants. In the later examples from Buffett’s life, i.e., those that match with the Individualist, Strategist and Alchemist, he exercises a kind of ‘mutual’ power that ensures that others get what they want as well. This shift from a ‘unilateral’ to ‘mutual’ use of power lies at the heart of the main transformation in Buffett’s life and is key to appreciating the leadership culture he and Munger have created at Berkshire.

Three examples from my study help to illustrate this development; Example 13. Dempster Mill (from the ‘Buffett the investor’ period in the early years up and until the end of The Buffett Partnership in 1969), Example 21. See’s Candy (from ‘Buffett the business leader’ period in the mid years and beyond, i.e., from when he took over as Chairman of Berkshire in 1970) and Example 32. Buffett acquires Burlington Northern (from the ‘Buffett the elder statesman’ period in more recent years and particularly since the death of his first wife in 2004). (See Table 1)

| Example | Period in Buffett’s career | Use of power |

| Eg 13. Dempster Mill | Buffett the investor | Transactional |

| Eg 21. National Furniture Market | Buffett the business leader | Transformational |

| Eg. 32 Burlington Northern Railway | Buffett the elder statesman | Mutually transforming |

Table 1. Buffett’s changing use of power

Dempster Mill

In 1956 Buffett took a controlling interest in Dempster Mill, a manufacturer of farm equipment and water systems. Buffett was more interested in the finances rather than the operations of the business and when things started to go wrong he framed the problem in those terms. In conversation with his partner, Charlie Munger, he noted “I’ve got this jerk running Dempster Mill and his inventories keep going up and up” (Schroeder, 2008, p.243). Buffett reacted defensively; he fired the CEO, laid off 100 staff, stripped the business of non-core assets, coerced the board into agreeing to a restructuring plan, and within two years had put the business up for sale. The plan worked. He made a handsome return on investment. But in the process a whole town rose up against Buffett and encouraged the previous owner to buy the business back. Buffett was a hated figure and was left wondering “were did it all go wrong”?

Perspectives. Buffett appears ‘subject to’ his third-person method. His investment method determined what he would buy, when he would buy and sell and how he would deal with management and staff. Buffett’s interest in the business does not extend beyond its financial gain and does not include the interests of employees, their families or the local community. From a pure investment perspective, Dempster Mill was an inefficient company that he was making ‘efficient’ and from which he would make a profit.

Timeframe. His timeframe is dictated by his method, i.e., sell when the price recovers or if it does not recover wait and sell off the assets of the business in a liquidation (zero to one dimensional time).

Feedback. Buffett accepts a form of single-loop feedback, but this is only from those pre-qualified to speak such as Charlie Munger and Harry Bottle (the new CEO), people he sees as having some relevant expertise (limited single-loop). He is not yet able to accept feedback from himself or from other outsiders including family and friends.

Use of Power. Buffett abrogates his power to his method and thus becomes dependent on it. In this case he takes a blunt approach; he replaces the CEO, fires many of the staff, uses the cash from the business to invest outside the business and then sells off the business at a profit. In the process he coerces the board, the business and the staff and while ultimately successful, he is still left wondering ‘where did it all go wrong’? Buffett became a hated figure among local people, something he appears both surprised and displeased at. This suggests that it was not his intention but rather the consequence of his action of which he was unaware.

Nebraska Furniture Market

Contrast Buffett’s behavior in Dempster Mill with his acquisition of Nebraska Furniture Market (NFM) (Example 21). In 1983 Buffett purchased 80% of NFM from Mrs. Rose Blumkin for €60 million. When the Blumkins indicated the price at which they were willing to sell, Buffett immediately agreed and without checking the stock inventory of the company. Buffett trusted the Blumkins. He even allowed Mrs. Blumkin a ‘cooling-off period’ should she decide to change her mind. Also, while the sale was being discussed, Buffett coached Mrs. Blumkin’s son as he considered an alternative offer (which incidentally was higher than Berkshire’s). As part of Berkshire’s offer, Buffett guaranteed that the family and current management would stay on running the business as before, which is still the case today.

Perspectives. In analysing NFM as an investment Buffett integrates multiple perspectives. He was aware of his own need for long-term business partners, the needs of the Blumkin family to stay on running the business as before and Berkshire’s needs for businesses with a sustainable competitive advantage. Such an integration of perspectives suggests Buffett was operating from an expanded fourth-person perspective.

Timeframe. Buffett’s timeframe is long-term, past to future (one dimensional linear time). Buffett however also sees timeless qualities in NFM which is suggestive of a two dimensional non-linear awareness of ‘present’ time as well.

Feedback. Buffett’s openness to feedback incorporates multiple sources, his own needs, those of Berkshire and those of the Blumkin family. Buffett’s gentle coaching of Louie and his sons is both masterful and full of integrity.

Use of power. Buffett’s use of power in dealing with the Blumkins, in talking about future partnership, being respectful of Rose Blumkin, accepting her word on figures, allowing her a cooling off period, is all suggestive of a type of Inter-Independent mutual and transformational type of power that seeks win-win outcomes.

Burlington Northern Railway

Fast forward another 25 years to 2009 and Buffett is making the largest investment of his career, i.e., a $33 billion acquisition of Burlington Northern Railway (Example 32). Buffett paid full price, i.e., 18 times BNSF’s earnings and said the acquisition was “an all-in-wager on the economic future of the United States” to which he added “I love these bets” (Berkshire Hathaway press release, Nov 3, 2009). Later in an interview with Charlie Rose on the PBS Network (13 Nov 2009), Buffett said that, “I felt it was an opportunity to buy a business that is going to be around for 100 or 200 years”.

Perspectives. Buffett incorporates multiple perspectives in his action. For instance, applying the four pillars of his investment approach (Buffett, 1977), BNSF is a business he knows and understands (Berkshire already owns 23%) and is within his circle of competence to evaluate. He knows and trusts the management and he believes the business has a sustainable future. In this case the margin of safety doesn’t lie in a percentage figure but in Buffett knowing and understanding the risk. Integrating these perspectives in his action suggest Buffett is make-meaning from an expanded fourth-person perspective.

Timeframe. Perhaps reflecting a three-dimensional view of time, Buffett is aware of time past, present and future (100 years), plus an ability to see himself actively shaping Berkshire’s future now. There was no other transaction in Berkshire’s history where he openly considered a 100 year timeframe. It is ironic that the less time Buffett has left with Berkshire the longer is his time horizon for the business.

Feedback. His acquisition of BNSF is perhaps both “transformational, strategic, structural” (double-loop) and “continual, visionary, spiritual” (triple-loop). The mission, the strategy and the behaviour all change as Buffett positions Berkshire for the post-Buffett era.

Use of power. His use of power is directed towards “mutually transforming” himself and Berkshire. The transaction is also transformative for Berkshire’s shareholders in that Berkshire is becoming a more stable conglomerate index of businesses rather than the more volatile mix of insurance and trading activities associated with Berkshire in the past. It is also transformative for Buffett. In the same way that giving away his money to society challenged his overall mission in life to accumulate money, the BNSF acquisition represent a similar challenge to his overall vision for Berkshire.

What is clear from these examples is how Buffett changed from a ‘transactional to transformational to mutually transforming’ use of power (see figure 2). In the case of Dempster Mill, his use of power was coercive and manipulative where, in the absence of agreement, he relied on the transactional power of his shareholding in the company. He exercised ‘power over’ the others involved. In the case of his acquisition of Nebraska Furniture Market his use of power was inclusive and mutual and no action was taken without collaboration with others. In this case he exercised ‘power with’ others. By the time he gets to Burlington Northern, Buffett exercises a kind of mutually transforming power as he prepares Berkshire for the post-Buffett era. His leadership may now be described as ‘leading so others can develop’ rather than follow. It is not an understatement to say that the future of Berkshire relies on Berkshire’s managers continuing to be leaders rather than followers. The compelling vision for the future is now theirs and is no longer limited to Buffett and Munger.

Figure 2. Buffett’s Changing Use of Power

From a development perspective, a mindset that ordinarily uses unilateral power to get what they want could not have created the kind of mutual leadership culture that we now see at Berkshire. There is no doubt that Buffett’s changing circumstances demanded a change in his leadership approach but it still required that he change his mind as well. Just because we need to change does not mean we will. We may also observe that while we can temporarily change our behavior, we need to change our minds before it can be made permanent. Recall the big shifts in Buffett’s thinking and behavior from owning lots of small stocks for the short-term (during the Buffett the investor period) to owning few businesses for the long-term (starting with the Buffett the business leader period). These weren’t short-term behavioral changes, rather they represented a fundamental change in his mindset which was then reflected in what interested him.

The change in his timeframe, from short-term to long-term, also had consequences for his engagement with management. Buffett had previously shown little interest in the affairs of management. His attention was primarily on the finances. Thus as he acquired new businesses he was not bringing management experience and so could not rely on the power of his management expertise. He could have relied on the transactional power of his ownership (unilateral power) but he knew that given his strengths and weaknesses that would not have encouraged the kind of leadership behaviour Berkshire required. His main challenge was to ensure that the managers of the businesses he acquired would stay on running their businesses as before, free from his intervention. This in turn required creating the conditions under which the managers could thrive and develop themselves.

In the process Buffett and his business partner Charlie Munger have created an unusual leadership culture at Berkshire, a company that now incorporates 80 or so separate operating businesses employing 250,000 people and with only 24 people in head office. In other words, there are no managers to manage the managers. To paraphrase Charlie Munger, Berkshire has delegated authority almost to the point of abdication. To which he adds “If your system is to decentralize, …… what difference does it make how many we have” (Berkshire AGM Notes, 1013)? Think for a moment just how unusual that is. How can such an extreme form of decentralisation work so well? Underpinning their approach is something even more unusual in to-day’s hyper competitive business enviroment, i.e., trust. Buffett and Munger say that the Berkshire’s leadership culture is based on a “a seamless web of trust” (Berkshire AGM notes, 2009). And there is plenty of evidence of this. Berkshire’s senior managers don’t have contracts. They aren’t required to submit annual budgets. They don’t have to implement any ‘the way we do it around here kind of thinking’; there are no requirements for annual get-togethers, no ‘senior team building’, no forced socialising and no expectations of any centralised branding.

Surely that sort of approach can’t work though? Where are the checks and balances? Who is making sure the managers are being trustworthy? And of course if you are asking those questions you don’t understand how a seamless web of trust works. The kind of ‘power over’ you see with the use of unilateral power is primarily based on fear, whereas the kind of ‘power with’ that you see with the use of mutual power is primarily based on love. Consider what Buffett has to say on the difference between love and fear and how love underpins the leadership culture at Berkshire;

“I don’t believe in fear as a manager………I don’t operate like that. I don’t like this life. Probably certain circumstances call for it: operate this way for a policeman. I believe the most powerful force is love and that is the most effective way of dealing with people. I would not want to live a life where people are afraid of me. People don’t operate well under fear. Some circumstances where mutually assured destruction is the end result, fear is good. But not at Berkshire Hathaway, love is way better to operate. By the way, how did Machiavelli do? There is no religion of Machiavelli 500 years later, is there”? (Gad, 2007).

The Paradox of Development

In their review of the literature on constructive-developmental theory, McCauley et al (2006) note what little impact the developmental research has had on the mainstream literature in leadership. This is indeed curious. From a developmental perspective, we can see that that the kinds of capacities we associate with leadership success; capacity to take multiple perspectives and come to a clear and decisive action, capacity to create a compelling long-term vision with others while also being able to deal with present realities, a capacity for openness to feedback from self, others and the world and a capacity to use power that is mutually transforming of self, others and the circumstances, all emerge with development. What we also see is that much of the effort in leadership development focuses on leadership ‘competencies’, i.e., the skills, knowledge and experience associated with being effective in a role. These of course are important as are the energy and passion a leader brings. Capacity for leadership however is something different – capacity is associated with a vertical development in one’s internal meaning-making which affects all aspect of our lives including our leadership.

Buffett says that he looks for three qualities in a manager, “integrity, intelligence, and energy” and to which he adds “and if you don’t have the first, the other two will kill you. You think about it; it’s true. If you hire somebody without [integrity], you really want them to be dumb and lazy.” Unlike intelligence we are not born with an integrity quotient, and this applies for Buffett as well. It is worth recalling that Buffett regularly stole from Sears department store as a teenager and there are many examples from his biographies of him acting ‘un-consciously’. Integrity on the other hand is associated with acting consciously – knowing yourself and knowing why you are doing something. As Buffett says, you can have all the intelligence, skills, passion, energy and experience you like (i.e., all the competencies), but if you don’t have the character and integrity to go with it, then these attributes can be a weakness as much as a strength.

This emphasis on ‘integrity’ seems like ‘common sense’ and yet the mainstream literature on leadership does not focus on it? Are they perhaps missing the paradox of leadership development? Viktor Frankl, in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, described the ‘paradox of happiness’ and how we can’t pursue the benefits of happiness; rather the benefits of happiness ensue from engagement in meaningful relationships and activities. And so perhaps it is with leadership. We can’t pursue the benefits of leadership, rather the benefits of leadership ensue from our development. From this perspective, it is not all curious that the mainstream literature would focus on the competencies of leadership and largely ignore the capacities. As the research indicates, less than 5% of managers/leaders to-day get beyond the Dependent and Independent leadership action-logics where competencies are the main focus. The dependent leadership action-logics are associated with the Opportunist and Diplomat, the Independent with the Expert, Achiever and Individualist and the Inter-Independent with the Strategist and Alchemist. And, according to developmental theory, it is only at these later action-logics (Strategist and Alchemist) that leaders can reliably transform their organisations to which I should add, they need the competencies associated with effective leadership in their particular field as well.

Operating from one of these early paradigms, there is an assumption that leadership can be known, i.e., that there is a way of leading and of being a successful leader that requires the necessary skills, attributes and experience associated with decisive leaders, ones that operate within command-and-control type, top-down leadership structures, and where there are leaders and followers. Such an approach works well with ‘things’ but not so well with ‘people’. Recall the example of Buffett and Dempster Mill. He thought he was doing a good job sorting out the company’s inventories and making the business more efficient, and yet it all blew up in his face. He never considered the people involved. Reflecting on this Buffett realized that not only did he need to understand how ‘things’ worked but if he was to be a successful leader, he also need to understand how ‘people’ worked as well, including himself.

Operating from a later paradigm, leadership is not something that can known by the leader himself, rather it is something that emerges through collaboration with others dealing with the real issues at hand. In Berkshire’s case, Buffett didn’t have to know how the Berkshire businesses could be managed. He just had to figure out how he could create the conditions under which the managers of those businesses were guaranteed their autonomy. To this he added his encouragement and support. In other words, Buffett had to learn to trust his managers (the seamless web of trust) and let them get on with it, including making their own mistakes. Sometimes this has gone wrong for Berkshire, but most of the time it has worked out spectacularly well. “As Buffett noted, “I have 40 CEO’s working for companies owned by Berkshire. Since 1965, not one of them has left Berkshire Hathaway” (Gad, 2007).

All things are interrelated and so perhaps it is unwise to isolate one factor, such as Buffett’s development, and say that is the primary factor in explaining his success as a leader. That was never the conclusion from my study. Non-developmental factors were considered equally as important and in some cases more important. And yet it is through the development in Buffett’s meaning-making that Buffett was able to create the kind of leadership culture that now exists at Berkshire and which is fundamental to Berkshire future success in the post-Buffett era. Over his long career, Buffett has developed his capacity to engage with himself – to know himself – and with this a development in his awareness and integrity. In addition, Buffett has developed his capacity to engage with others as reflected in his ability to create mutuality with those around him. These were not capacities Buffett exhibited earlier in his career and they weren’t characteristics that he inherited at Berkshire. Both of these central leadership capacities have emerged with his development.

Conclusions

Adult developmental theory is an acquired taste and is currently limited to a small group of scholars, who, as noted earlier, have had little impact on the mainstream literature in leadership studies. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that, until now, adult developmental theory has lacked an exemplar, someone such as Buffett, whose development has gone through the predicted order of development as described by the theory. Most of us would assume that Buffett’s development is unique to Buffett. When we look through a developmental lens however, we can see that Buffett has gone through at least seven transformations in his meaning-making that can be mapped to developmental theory. The content and context of his life are unique to Buffett but the generalised patterns of development are not.

You may choose to ignore this conclusion as not fitting your view of how his development occurred or you can decide that such a conclusion may be worthy of further exploration. If the latter is the case, then you may find yourself also wondering, ‘what has this developmental theory got to say to me about how I may develop’? My sense is that it merely raises the question of the importance of development. Studying Buffett’s development is unlikely to have any impact on your own development. Writing a developmental autobiography of your own life, and referencing it back to the action-logics in the theory, may however provide some real insights, as it did for me. (Torbert & Fisher, 1992). It was only when I had this immediate experience of development that I was open to both seeing how development occurred in others, such as Buffett, and reflecting on how development may occur in my life.

Perhaps highlighting Buffett’s development and the impact it had on his success as a leader will also help to pry open the leadership field to a new understanding of the ‘paradox of leadership development’ and how you can’t pursue the benefits of leadership, rather the benefits of leadership ensue from your development. In taking this approach however, the developmental community need to acknowledge that when it comes to effective leadership, it is not just about the developmental ‘capacities’ but also about the skills, knowledge, intelligence, experience and energy (the competencies) in a particular field. This was certainly the case for Buffett where the non-developmental factors were equally important to the developmental factors. Where the competencies are already in place however or can be easily acquired, the big difference in leadership effectiveness will come from a development in one’s ‘capacity’ to lead in whatever leadership circumstances we find ourselves, as a parent, a teacher, a community worker or workplace manager. What we can learn from Buffett then is not to try and copy him but to know that he developed his character and that his character development impacted the success of his leadership.

There are some questions that have not been addressed in this article which are directly related to what ‘we’ can learn from this study. For instance, if I decide I want to develop myself further, ‘what sort of developmental interventions are most likely to help me’? The research on this equivocal (Borders, 1998; McCauley et al., 2006). Some interventions are said to aide developmental movement, others not. In both cases the interventions have little to do with the theory. It seems that while developmental theory is good at explaining how development has occurred it is not so good at helping you to develop. This is another paradox, that you can’t pursue the benefits of development, rather the benefits of development ensue from engagement with the real issues and relationships in your life. Like a cool breeze that comes in when you leave the window open, you cannot invite your own development. All you can do is leave the window open. In fact the more you try and attain the benefits of development, the less likely it is to occur, but more of that from my personal reflections in article 3….

References

Cook-Greuter, S. (1999). Postautonomous ego development: A study of its nature and measurement. Dissertation Abstracts International, 60, 06B. (UMI No. 993312).

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2000). Mature ego development: A gateway to ego transcendence? Journal of Adult Development, 7(4).

Cook-Greuter, S. (2005). Ego Development: Nine Levels of Increasing Embrace. Adapted and expanded from S. Cook-Greuter (1985) A Detailed Description of the successive stages of ego-development. Unpublished manuscript.

Berkshire Hathaway press release (2009). Berkshire Hathaway To Acquire Burlington Northern Santa Fe Corporation. Downloaded from ‘News Releases’. www.berskhirehathaway.com , January 2010.

Borders, (1998). Referenced in, Supervision Experience and Ego Development Of Counseling Interns, PhD Thesis, Sara Meghan Walter, Spring 2009.

Gad, S. (2007). Study visit to Berkshire Hathaway by MBA students from Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia. Downloaded from http://www.intelligentinvestorclub.com/downloads/Warren-Buffett-University-Georgia.pdf

J. V. Bruni and Company. Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting May 2, 2009 Complete Notes. 1528 North Tejon Street Colorado Springs, Colorado 80907 (719) 575-9880 or (800) 748-3409. Downloaded May 2013.

Kegan, R. (1980). Making meaning: The constructive-developmental approach to persons and practice. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 58, 373 −380.

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R. & Lahey, L. (2009). Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock potential in yourself and your organization. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Press.

Kilpatrick, A. (2004). Of permanent value: the story of Warren Buffett. AKPE, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Lowenstein, R. (1997). Buffett: The making of an American capitalist (2nd ed.). London: Orion Books.

O’Loughlin, J. (2002). The Real Warren Buffett. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London, UK.

Rooke D. & Torbert W. (2005a). Seven Transformations of Leadership. Harvard Business Review, 83(4), 66 −76.

Schroeder, A (2008). The Snowball. Warren Buffett and the Business of Life. Bantam Books, September 2008.

Starr, A. & Torbert, B., (2005). Timely and Transforming Leadership Inquiry and Action: Towards Triple-loop Awareness. Integral Review 1.

Torbert, W. (1976). On the possibility of revolution within the boundaries of propriety. Humanitas. 12, 1, 111-148.

Torbert, W. R. (1987). Managing the corporate dream: Restructuring for long-term success. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin.

Torbert, W. R. (1991). The power of balance: Transforming self, society, and scientific inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Torbert, W. & Fisher, D. (1992). Autobiographical awareness as a catalyst for managerial and organizational development. Management Education and Development, 23, 184-198.

Torbert, W. (1994). Cultivating postformal adult development: Higher stages and contrasting interventions. In M. E. Miller & S. R. Cook-Greuter (Eds.), Transcendence and mature thought in adulthood (pp. 181−203). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Torbert, W. R., Cook-Greuter, S. R., Fisher, D., Foldy, E., Gauthier, A., Keeley, J., et al. (2004). Action inquiry: The secret of timely and transformational leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Warren Buffett quotes. http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/76790-somebody-once-said-that-in-looking-for-people-to-hire

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Boston: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2003). Introduction to excerpts from volume 2 of the Kosmos Trilogy. Excerpt A: An integral age at the leading edge. Excerpt B: The many ways we touch: Three principles helpful for any integrative approach. Excerpt C: The ways we are in this together: Intersubjectivity and interobjectivity in the holonic kosmos. Excerpt D: The look of a feeling: The importance of post/structuralism. Available in full at http://wilber.shambhala.com/.

Wilber, K. (2006). Integral spirituality: A startling new role for religion in the modern and postmodern world. Boston, MA: Integral Books.

About the Author

Edward J. Kelly (BA, MBA, Ph.D) is aged 53 and lives in Dublin Ireland. Over the years he has been an adventurer, a businessman and a researcher. As an adventurer, he entered the Guinness Book of Records in 1990 having organised and participated in the longest most expensive taxi ride in history from London to Sydney. As a businessman he founded and managed his own company in the telecoms sector and as a researcher (last eight years) he has explored various approaches to leadership development and completed a PhD on one of the world’s most successful investors and business leaders, Warren Buffett. He now works as a facilitator helping individuals, teams and organisations transform themselves, their networks and their businesses.

Buffet is indeed a leader leader. I which that he will live long to continue to impact us the young generation.