1/15 – The Long and Winding Road: Leadership and Learning Principles That Transform

Brigitte Harris and Niels Agger-Gupta

Our Journey as a School of Leadership Studies

Brigitte Harris and Niels Agger-Gupta

Brigitte Harris

Niels Agger-Gupta

The MA Leadership program was the first offering of the newly created Royal Roads University (RRU) in 1996. The program was designed for mid-career professionals with at least five to ten years of leadership experience. Designed on pioneering, paradigm-changing but rigorously referenced experiential adult learning principles[i], this program has been successful from the beginning, consistently attracting up to 200 students annually from across Canada. The two-year program, involving short residencies at the RRU campus in Victoria, BC, blended with online courses, and a capstone action research project, drew adults from diverse backgrounds together in what became close-knit cohorts.

This experiential and feedback-rich competency-based program attracted faculty as well, who embraced what they saw as a ground-breaking approach to post-secondary graduate education. The program spanned the range of current leadership thinking, and the program was structured in what Short (1998) called, an “inside-out” approach, focusing first on the student’s own personal constructs, mental models, and understandings of relationships and styles of learning and knowing, followed by leading teams and then organizational change. The competency-based program taught:

- leading self – personal leadership, managing own learning;

- leading others – helping others learn, communication, team leadership and group facilitation; and

- leading whole organizations – systems thinking, organization change, and organizational research and inquiry.

Over the next decade or so both the university and the program grew and changed, but the program always managed to retain the ‘magic’ coming from the “strong DNA” of its design principles (M. Hamilton, personal communication, 2010), despite adjustments to the length of residencies and tweaks to the program content. Residencies (one each early in Year 1 and Year 2) in 1996 were five weeks in length, and then shifted to four weeks, then three, and, since 2011, to residential retreats of two weeks in the context of an 11-week blended experience. However, while the program’s popularity continued, and student success was always the major concern of faculty and administration, behind the scenes there were conflicting ideas about the School’s direction, philosophy, and structure. When this was combined with occasionally conflicting personalities, the road became rocky.

Eventually, after several years of divisive management and interpersonal conflict that led to high levels of faculty and staff turnover, the School of Leadership Studies (SoLS) developed a reputation as a “problem child” in the University community. As a result of reorganizations, retirements, and extended sick leaves, only two core (full-time) faculty members remained out of the full complement of seven, and many of the best and brightest of the associate (contract) faculty, who were vital to program delivery, no longer taught for us. The remaining two core faculty members were exhausted and demoralized, struggling to keep the programs running.

In 2010, SoLS started down a road of profound transformation. Changes in the School’s and University’s administration brought an opportunity for renewal. Key associate faculty were invited back to help reshape the MA Leadership program. In 2011, SoLS hired three new core faculty members. One of the new hires became the first director the School had since 2005. (A series of temporary directors in an “acting” role had previously filled the director position.) Significantly, the new director was also the first to have been selected through a newly implemented transparent selection process involving the School’s faculty and staff as the primary decision-makers. In 2012, the Institute of Values-Based Leadership rejoined, and the Centre for Health Leadership Research joined the School. The addition of these two research units added two core faculty members to SoLS. The challenge was to integrate two new units and new faculty into a School with a recent troubled history. In addition, we started to move from a School with two closely related, highly successful programs — the MA Leadership and MA Leadership Health Specialization — to a School with multiple programs. SoLS was changing and we needed to come together as a collaborative and collegial team to create a new entity we called, with tongue in cheek, “School of Leadership Studies 2.0”.

Over the next year, we, SoLS faculty and administrative staff engaged in several retreats, and many discussions to forge the new entity and our new identity. We felt it was essential to understand where the School had come from, and to work through the old conflicts and hurts to enable us to identify future directions. The early meetings were uncomfortable as we struggled to move beyond the old unproductive interpersonal patterns to set the groundwork for a revitalized School that was inclusive of old and new perspectives, and open to taking advantage of the opportunities being presented to our new team. While we identified shared values, we struggled with a mission and vision for the School as a whole. It seemed too early in the process to have a mission and values discussion. We needed to step back and identify what we believed about leadership and our role as leadership educators and researchers.

What follows is a description of the results of the “breakthrough” conversation, in which we identified four principles that underlie all of our leadership education, and research and scholarship activities. We call it a breakthrough because this first agreement on what we believed and held close to our hearts has allowed us to continue to build shared understanding, improved relationships and a more productive and collegial workplace.

The Four Principles[ii]

Leadership as Engagement

Our colleague, Marilyn Taylor (2011) describes the shift in the post-conventional leadership discourse from leaders as serving self to serving the interests of the group, and leaders who are characterized by “personal purpose and responsibility, values-focused, shared leadership and collaboration, authenticity, and transparency” (p.189). Thus, in contrast to the view of leader as all-knowing hero or heroine, we believe that the role of the leader is to influence and listen deeply, to engage others in creating a shared vision, and to harness the hearts and minds of the people in an organization in forging new directions. Leadership as engagement is about leaders working to build organizations to help people grow and thrive. Engaged leaders motivate through inspiring people, encouraging people to experiment and learn from experience, and coaching and mentoring others to help them build competence (Kouzes & Posner, 2007). Leadership is not only about strategy and decision-making; it is also about engaging the people you are leading, respecting what they contribute to an organization, and enabling them to do so (Quinn & Thakor, 2014). As leadership educators who believe that leaders’ purpose is to serve the common good, we work to model and help students build a similar sense of purpose and engagement in their settings. And we are living leadership as engagement as we make our own journey of transformation as faculty and as the School.

Leadership as engagement is about leaders enabling the talents, skills, and aspirations of others in alignment with a community’s or an organization’s purpose. We believe this leadership approach is essential to helping people to work together effectively toward a common purpose and the creation of a high quality of life. At the same time such engagement allows for nimble responses to challenges and turbulence in all the contexts and systems of the local, regional, and global environments. This “social intelligence”, or “humble inquiry” (Schein, 2013), is an essential complement to the technical requirements of leading an organization. We believe that the leadership we teach students is the same one we enact with each other and with our university stakeholders.

For example, every year about 180 students pursue the MA Leadership capstone (culminating project or thesis), leading an inquiry into a potentially beneficial organizational change in a real organization. Since the start of the program, MA Leadership capstones have taken place in organizations in every sector, including business, education, government at the municipal, provincial, and federal levels, policing and the military, healthcare, and non-profit social services agencies. Students work with an organizational sponsor to develop and implement an inquiry into an issue, problem, or opportunity of genuine organizational concern. Topics have ranged from improving leadership training, health systems improvement, succession planning, employee engagement, municipal downtown re-development, and program planning, to name only a few. The fundamental process is to meaningfully engage organizational stakeholders and create opportunities for engagement and group decision-making on next steps (Rowe, Piggot-Irvine, Graf, Agger-Gupta, & Harris, 2013; Raelin & Coghlan, 2006).

The capstone project of Lidia Wesolowska [iii], in co-designing a process for downtown redevelopment with the City of Swift Current, Saskatchewan (Wesolowska, 2013) provides an example of the type of service learning our students do. Lidia developed a process for meeting with different layers of stakeholders within the City, who had not previously been consulted, and invited them back to a group gathering to help her sponsor, the City, develop a strategic plan for the redevelopment process. This was a new approach for the City which routinely made decisions after involving only a few stakeholders. Another student, Laura Zaroski, developed a similar process in her work in developing a leadership training process with Emergency Medical Services in the Calgary Region of Alberta Health Services (Zaroski, 2013). In each case, findings emerged from a process of gathering data within a confidential framework authorized by the RRU Research Ethics Board which required eliminating any power-over coercion or conflicts of interest, and bringing anonymous findings back to the larger organizational group of stakeholders for action planning. In each case, the process involved issues that were highly meaningful and engaging, and typically served to align stakeholder thinking and generate good energy for moving forward. As these examples show, engaged leadership involves giving meaningful voice to those who would be impacted by decisions.

Engaged Scholarship

We believe that our research and that of our students must make a positive difference in the organizations, communities and professional groups within which we conduct it. This is the very essence of the concept of “engaged scholarship”. It is a process by which scholars collaborate with others — including other scholars, stakeholders and practitioners — to co-create knowledge (Barge, Jones, Kensler, Polok, Rianoshek et al., 2008). The process brings together people with “different points of view”… providing us with “a much deeper understanding of a phenomenon than we ever could [gain] by ourselves” (Van de Ven, 2011, p. 43). In other words, through engaged scholarship we can benefit from diverse perspectives that create the opportunity to generate new perspectives and solutions for social benefit. The leaders’ role in our engaged scholarship model is to promote the synergistic and dialectical relationship among scholars, practitioners and stakeholders. In practice terms, this means leaders consistently need to ask who else should be part of the conversation on any topic. Inviting those who are not normally part of the conversation provides opportunities for insight, positive connection and change (Spears, Noble, & Wheatley, 2002).

“Engagement is a relationship that involves negotiation and collaboration between researchers and practitioners in a learning community” (Van de Ven, 2007, p. 7). A learning community is “an environment where people can learn together, for the collective good and for themselves” (Kearney & Zuber-Skerrit, 2012, p. 402). Since the beginning of the MA Leadership, learning communities have been a primary feature of the program’s design. Our students generally enter and complete their program with the same cohort of learners, within which they develop deep relationships that support and enhance their learning. In our experience, these relationships foster an open and trusting environment where students can engage with each other to deepen their understandings, to support and learn from each other, to coach and provide honest feedback and to question each other’s assumptions. This learning approach is one that we apply in our facilitation and which extends naturally to our scholarship.

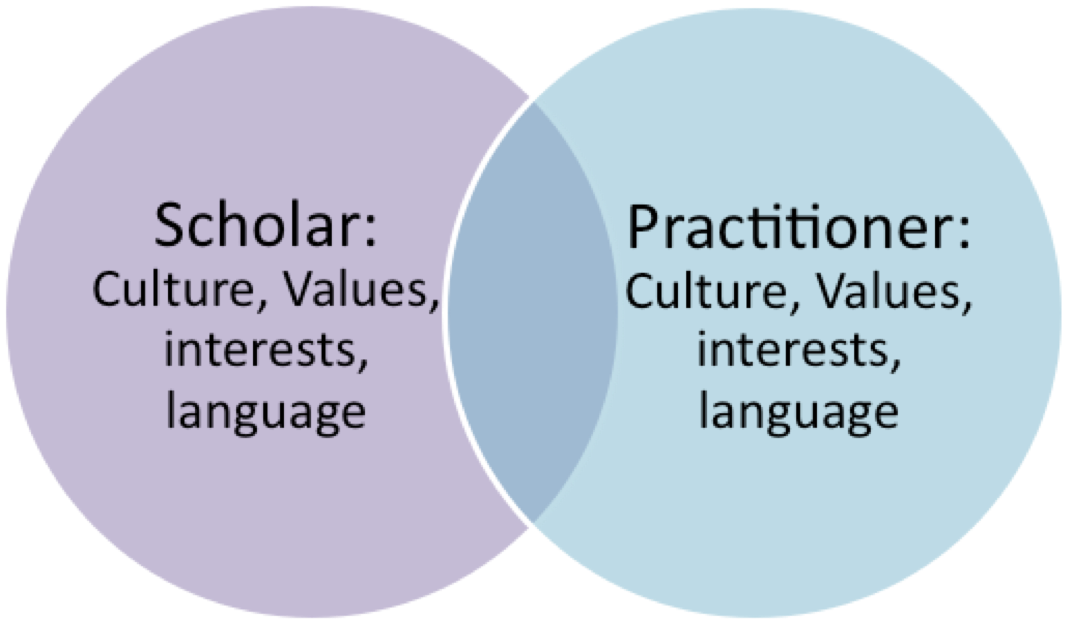

The literature describes a deep divide between scholarship and practice, and what scholars and practitioners know, do and value (Van de Ven, 2007; McKelvey, 2006). In contrast, our faculty are scholar-practitioners; they bring their practitioner experience to their teaching and facilitate learning that students can apply in their workplaces. Therefore, we believe that the great divide between scholarship and practice does not describe our core or contract faculty, or our students, who, as experienced leaders, are practitioners and learning to do applied research in an organization. While scholars and practitioners may have distinct interests and values related to their roles and organizations, those of scholar-practitioners have significant overlap.

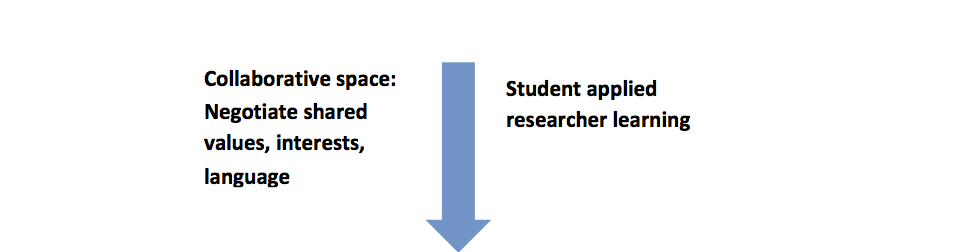

Faculty members’ applied research and scholarship plays a key role in the teaching and learning in our programs. The overlapping space between scholars and practitioners (Figure 1) is where we facilitate students’ learning of applied inquiry skills. Students in our programs learn a process for connecting their practitioner knowledge with inquiry methods, research ethics, and the scholarly literature. We see students as “co-creators of knowledge” (Fretz & Longo, 2010, p. 317) and co-creators of “an engaged academy” (p. 313). In their MA Leadership capstone projects, students plan and carry out an action research project within an organization, often the one in which they work, to address a real world problem or opportunity and to engage stakeholders in creating positive change. By engaging our students as co-creators of knowledge and as engaged scholar-practitioners, the learning experience can become transformational (Fretz & Longo, 2010), which will be discussed in more detail in the section on “Learning for transformation”.

Figure 1: Intersection of scholar-practitioner worlds

The School offers two capstone project options: an Organizational Leadership Project (OLP) or a thesis. Both use an action research approach, but the differences between the two are reflected in Torbert and Taylor’s (2008) concept of first-person, second-person, and third-person research. First-person research, more generally, is about the researcher addressing a personal need for knowledge, while second-person research is about addressing the challenge or opportunity posed by the organization in the practice field. Third-person research is about inquiry that results in findings of broader interest or that lead to policy changes. Frequently third-person research is also thought of as inquiry that leads to new theoretical knowledge. In the case of the OLP, we expect that projects will primarily address first and second-person research matters, although the best of these respond on all three levels. The expectation for theses are that they address all three forms of research, but we particularly expect thesis students to respond to the action purpose of the organizational inquiry and develop new theory about the intersection of scholarship and practice related to the research question. In this way, we partner with students not only in knowledge creation and application but also in working towards the common good.

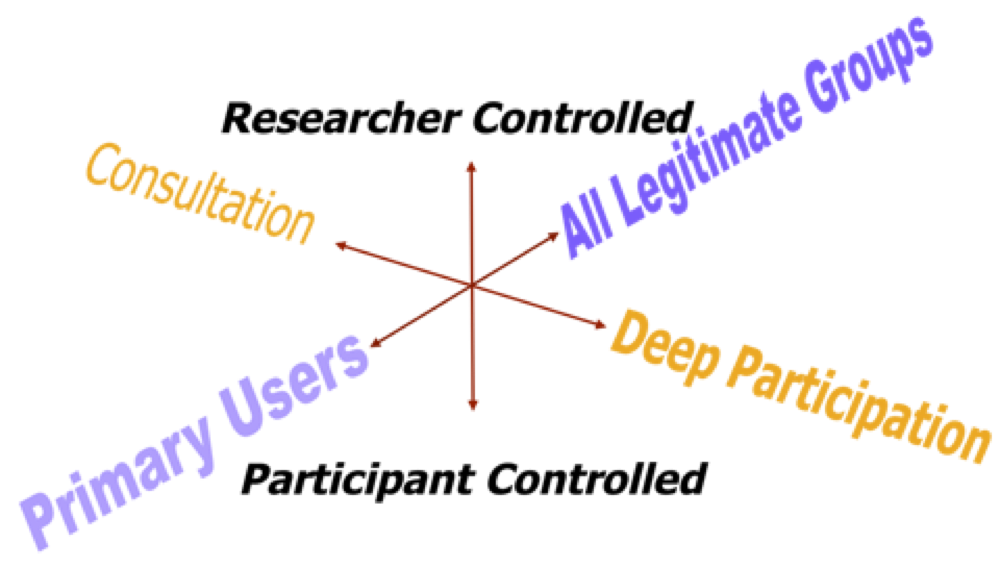

Figure 2 shows three intersecting dimensions of tension in leadership scholarship. Scholarship tends to be located somewhere along each of these continua, and rarely at the poles. The key questions are fundamentally about an epistemology and vision for leadership: who controls the direction, depth, content, process, and outcomes of any inquiry? Does an objective researcher/leader control decisions and outcomes, while employees or community members are simply instrumental to gaining information and knowledge for the leader? Or is the inquiry what the critical theorist Habermas would identify as “emancipatory”, seeking to increase engagement, personal autonomy, and community, and devolve decision-making authority to the lowest possible level in the context of an organization (Park, 1999)? Weisbord (2012) calls for organizational leadership and scholarship in the service of increasing human dignity, meaning, and community. Our school’s focus on this kind of aspirational and positive engagement in leadership mirrors the kind of leadership scholarship we seek to foster.

Figure 2: Polarities of control and devolving decision-making (Adapted from Cousins & Whitmore, 1998)

Since 2012, the infusion of new faculty has dramatically increased the output of scholarship of School faculty in the areas of health leadership and networks, the future of leadership education, nursing research, collaboration, action research, evaluation, community and participatory research, sustainability, global leadership, program design, and appreciative inquiry. This work involves community and organizational engagement and inclusion, and provides aspirational models to support our work with our students.

Orientation to Possibility

Zander and Zander (2002) tell a story about two shoe factory marketing scouts in a region of Africa studying prospects for expanding business. One sends back a telegram saying, “SITUATION HOPELESS STOP NO ONE WEARS SHOES”. The other sends a telegram saying: “GLORIOUS BUSINESS OPPORTUNITY STOP THEY HAVE NO SHOES” (p. 9). Their story illustrates, in a nutshell, the benefits of orientation to possibility and we have used it in our program for years.

The School’s orientation to possibility is about helping students understand the mystery of their organizational context with the perspective of explorer and adventurer, looking for opportunities to increase dignity, meaning, collaboration, and possibility. Such an orientation helps us to focus on the bigger issues of meaning and hope while being pragmatic about the resources, materials, and processes that will help us and our colleagues move toward a desirable future that has not yet been determined. Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros (2008) called this movement the “heliotropic hypothesis”, the concept that sunflowers move their large heads to stay facing the sun. The aspirational aspects of leadership (Quinn & Thakor, 2014) create the possibility of making a productive workplace a centre of dignity, meaning, and community (Weisbord, 2012).

An orientation to possibility is about understanding that perceived or actual barriers can be a motivator for creative thinking. “If we get curious about it, the disruption could lead to breakthroughs” (Holman, 2010. p. 114). Rather than being bogged down by these barriers, and the personal judgements these may have created, this principle is about taking a ‘learner’ perspective on investigating what might be possible under any set of circumstances (Adams, 2008). It also links to taking an appreciative perspective on understanding the stories and drivers of individual success. Both appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987; Holman, 2010), and positive psychology (Seligman, 2011; Snyder & Lopez, 2005) take a similar perspective on the benefits of identifying strengths.

Part of the process of finding these four principles for the School was to create a way to go to potentially dangerous places to actually hear each other before we could understand and integrate different perspectives. We were in the “red zone” where we were “unconsciously avoiding the person or people who would be most important in enabling us to move forward (Taylor, 2011, pp. 139-140). We needed to move to the “green zone”. This transition is based on finding one’s way forward to new learning, a new understanding or, perhaps, a new paradigm. One needs to be willing to let go of the old, and embrace the new, whatever that may be. The “green zone” (Taylor, 2011) is the frame of mind that allows the essential, critical values and relationships that created success and generated motivation in the past to help drive creativity In the new contexts moving toward the future.

School faculty and staff have come through the transition and are now better able to engage with one another with respect to creating new processes and programs, while feeling our individual personalities, perspectives and differences are accepted by others. This shift has allowed School faculty and staff to create new programs and a highly successful Leadership Conference. It has also allowed us to make on-going improvements in the MA Leadership program. It is important to state we are not looking for everyone to have complete agreement, or “make nice”; we are attempting to use our diverse perspectives to promote creativity in the School. Through our on-going attention to our orientation to possibility, we have been creating a respectful space for deep listening and real conversation to co-create our way forward. This is an on-going and living process.

Learning as Transformation

Fullan and Scott (2009) call on universities to develop the kind of leaders who can work effectively with others to create new approaches to resolving the messy and seemingly intractable problems confronting our world this century. This, they point out, requires a complete rethinking of what and how universities teach; universities that fail to do so risk becoming completely irrelevant. As faculty in a School of Leadership Studies, we have already identified our role in educating leaders to make a positive difference in the world. Through our extended community of graduates, we have heard story after story about our graduates using their learning to first transform themselves as leaders and learners and then to bring their new way of being in the world to transform their communities, organizations and society.

Given the challenges of sustained and rapid change, and unprecedented issues that threaten our very existence, we believe that our students, as leaders, need to be inquirers who know “how to construct new knowledge when faced with problems for which there is no known solution or even for which there is no known conceptual lens” (Raelin, 2006, p. 7). People must learn to “accept constant change and uncertainty, to engage constructively with the unfamiliar, and to adapt and learn in a continuously emergent context” (Taylor, 2011, p. 27). This kind of learning is not about learning facts, or what Bateson called “first order learning” (2000), given that anyone can look up “facts” on the Internet. Rather, the learning critical to our students and to future leaders is learning how to learn (second-order learning) and developing their own understandings and values about how they relate to the world (third-order learning). Fostering this type of learning means that we, as educators, must go beyond teaching knowledge and application of skills to creating a learning environment and activities in which students learn to transform themselves and society (UNESCO, 2008).

Taylor (2011) coins the term “emergent learning”, “a process through which we create a shift of mind, a fundamentally new perspective and approach to acting in the world” (Taylor, 2011, p. 2). Similar to Mezirow’s (1990) concept of transformational learning, Taylor extends the theory by emphasizing the embedded and ongoing nature of the learning in response to the uncertain and constantly changing world, and its relationship to action. Leadership, she observes, “flows naturally from emergent learning”, since the transformation “opens us to a different approach to engaging with the world” (p. 180). Like Taylor (2011) and Freire (1986), we believe that personal transformation can lead to social transformation that transforms people’s lives. And like Taylor and Freire, we believe that transformation needs to have a values base resonant with the social good.

Our MA Leadership program aims to develop the kinds of leaders the world needs and does so by promoting transformational learning, and the practice of leadership through emergent learning. Therefore, students of leadership need to learn to reflect critically and leadership educators need to support the development of critical reflection in their students. Taylor (2008) notes that “reflective journaling, classroom dialogue, and critical questioning” support this development (p. 11). Other features that promote critical reflection in students are: an open and safe learning environment, a learner-centred approach, student responsibility for their own learning, collaboration for exposure to other viewpoints, teamwork and shared ownership, and self-assessment and feedback (Taylor, 2000),

All of these features and practices are characteristics of our programs. We foster a positive, supportive and safe learning environment – a learning community that students are part of throughout the program. The learning community provides a supportive environment and a shared experience that enriches the learning and often forges friendships that continue after the program. It also brings together leaders from diverse sectors, of different ages, class, ethnic backgrounds, and experience to become members of a community with richly diverse perspectives. Team assignments throughout the program also support the learning community, creating a sense of shared ownership as well as fostering team skills. While students are members of a learning community, with responsibility for supporting the learning of others, we also see students as responsible for being active learners. For example, through critical reflection, one student realized that he would not succeed if he continued to wait for the professor to tell him the “right answers” as he had learned to do in his previous education; he needed to engage with the learning activities and others to learn. He realized that he would only get out as much as he put into the process (personal communication, June 2013). The learning environment is also feedback-rich, providing feedback from peers, faculty and self-assessment. For example, students work in learning partnerships (triads and dyads) for peer feedback, using a coaching approach. Faculty also use a coaching approach to providing ongoing and formative feedback and competency-based assessment, which allows them to give rich and specific feedback on what students did well and what students might do next time to improve or, what Goldman (2003) called “feedforward”.

The Journey Continues

The School of Leadership Studies’ own journey of transformational learning led us to identifying principles of leadership and learning that ground our practice. These principles allow us to innovate and provide guidance in terms of our shared values and beliefs. We have entered into a period of creativity in the School as a result of clarifying our purpose and improving our ability to listen to each other. We are now extending the conversation to our associate faculty.

We continue to actively engage the wider community in our work. For example, two faculty members engaged in extensive consultation with an international network of scholars, educators, and practitioners in developing a Masters in Global Leadership. Another faculty member used a community consultation model to develop a Bachelor’s degree in Leadership and Sustainability in collaboration with both the School of Environment and Sustainability, and a broad coalition of indigenous elders, educators, and community members. Similarly, as part of a major review of the MA Leadership, we conducted extensive consultations about new and emerging trends in leadership and leadership education while working to retain the elements of our program that make it such a powerful transformative experience for our students. As well, the School’s faculty members are increasingly active in their own engaged scholarship – research, projects, network building, global and community partnerships, publications, and conferences. We have also launched our own Leadership Conference that invites MA Leadership alumni and the broader community to co-create and disseminate new knowledge and innovative practices. In all of these activities, the four of the principles have been vital in helping us discern a way forward.

As members of the School of Leadership Studies, our learning journey, as we have discovered, is never finished, but rather becomes an ever deeper, more engaged renaissance of personal and School development. The four principles are holistic and integrated, acting as guideposts, and helping us to “walk our talk” with our students. Through the principles, we transform espoused theory into practical theory in use (Argyris, 1993). We apply the principles in our daily lives, and in our commitments to our students, to each other as colleagues, and to the School. Of course, the reality is that some days are challenging, while others are truly inspirational. The journey continues.

References

Adams, M. G. (2009). Change your questions, change your life: 10 powerful tools for life and work (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Argyris, C. (1991). Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Harvard Business Review, 69(3), 99–109.

Argyris, C. (1992). On Organizational Learning. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for Action. A guide to overcoming barriers to organizational change. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Argyris, C. (2008). Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press.

Argyris, C., & Schon, D. A. (1992). Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Barge, J.K., Jones, K.E., Kensler, M., Polok, N., Rianoshek, R., Simpson, J.L., & Schockley-Zalabak, P. (2008). A practitioner view toward engaged scholarship. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 36(3), 245-250.

Bateson, G. (2000). Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology (1st ed.). Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Brookfield, S. (1984). Self-directed adult learning: A critical paradigm. Adult Education Quarterly, 35(2), 59–71.

Brookfield, S. D. (1991). Understanding and Facilitating Adult Learning: A Comprehensive Analysis of Principles and Effective Practices. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cooperrider, D., & Srivastva, S. (2001). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In Appreciative Inquiry: An Emerging Direction for Organization Development (D.L Cooperrider, P.F. Sorensen Jr., T.F. Yaeger, & Diana Whitney (Editor) (eds). Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing.

Cooperrider, D. L., Whitney, D., & Stavros, J. M. (2008). Appreciative Inquiry Handbook: For Leaders of Change (2nd ed.). Brunswick, Ohio: Crown Custom Publishing.

Cousins, J.B., & Whitmore, E. (1998). Framing participatory evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation (Special Issue: Understanding and Practicing Participatory Evaluation), 80, 5-23.

Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and Education. New York: Touchstone.

Freire, P. (1986). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Freire, P. (2005). Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Continuum.

Fretz, E.J., & Longo, N.V. (2010). Students co-creating an engaged academy, pp. 313-335. In H. Fitzgerald, C. Burack, & S. D. Seifer (eds.) Transformation in Higher Education: Handbook of Engaged Scholarship (vol. 1). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

Fullan, M. & Scott, G. (2009) Turnaround Leadership for Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Goldman, M. (2003). Try feedforward instead of feedback. Journal for Quality and Participation, 26, 3, 38-40.

Holman, P. (2010). Engaging Emergence: Turning Upheaval into Opportunity. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Horton, M., & Freire, P. (1990). We Make The Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Kearney, J. & Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2012). From learning organization to learning community: Sustainability through lifelong learning. The Learning Organization, 19,5, 400-413.

Kegan, R. (1982). The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Knowles, M. S. (1984). Andragogy in Action: Applying Modern Principles of Adult Learning (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kolb, D. A. (1983). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (1st ed.). London: Prentice-Hall.

Kolb, D. A., & Fry, R. E. (1975). Towards an applied theory of experiential learning. In C.L. Cooper (ed.), Theories of Group Processes. London: Wiley.

Kouzes, J.M. & Posner, B.Z. (2007). The Leadership Challenge (4th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

MacKeracher, D. (2004). Making Sense of Adult Learning (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

McKelvey, B. (2006). Van de Ven and Johnson’s “Engaged Scholarship”: Nice try, but… The Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 822-829.

Mezirow, J. (1990). Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood: A Guide to Transformative and Emancipatory Learning (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000a). Learning to think like an adult: Transformation theory: core concepts. In J. Mezirow and Associates (eds.) Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000b). Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J., & Taylor, E. W. (Eds.). (2009). Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights from Community, Workplace, and Higher Education (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Park, P. (1999). People, knowledge, and change in participatory research. Management Learning, 30(2), 141–157.

Quinn, R. E., & Thakor, A. V. (2014). Chapter 9: Imbue the organization with a higher purpose. In J. E. Dutton & G. M. Spreitzer (Eds.), How to be a Positive Leader: Small Actions, Big Impact. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Raelin, J. A., & Coghlan, D. (2006). Developing managers as learners and researchers: Using action learning and action research. Journal of Management Education, 30(5), 670–689.

Raelin, J.A. (2006). Taking the charisma out: Teaching as facilitation. Organization Management Journal, 3(1), 4-12. Retrieved from www.omj-online.org

Rowe, W., Graf, M., Agger-Gupta, N., Piggot-Irvine, E., & Harris, B. (2013). Action research engagement: Creating the foundation for organizational change. Action Learning, Action Research Association Inc., Monograph Series 5.

Scharmer, C. O. (2009). Theory U: Leading From the future as it emerges. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Schein, E. H. (1995). Process consultation, action research and clinical inquiry: are they the same? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 10(6), 14–19.

Schein, E.H. (2013). Humble Inquiry: The Gentle Art of Asking. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London: Temple Smith

Schön, D.A. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Seligman, M.E.P. (1994). What You Can Change and What You Can’t. New York: Knopf.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press.

Senge, P. M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday.

Short, R. R. (1998). Learning in Relationship: Foundation for Personal and Professional Success. Bellevue, Washington: Learning in Action Technologies.

Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S.J. (2005). Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Spears, L.C., Noble, J. [interviewers], & Wheatley, M. [interviewee] (2002). The Servant -Leader: From Hero to Host: An Interview with Margaret Wheatley. Retrieved from: http://www.margaretwheatley.com/articles/herotohost.html

Taylor, M.M. (2011). Emergent Learning for Wisdom. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Taylor, E.W. (2008). Transformative learning theory. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 119, 5-15.

Torbert, W. R., & Taylor, S. S. (2008). 16 Action Inquiry: Interweaving Multiple Qualities of Attention for Timely Action. In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research (pp. 238–251). London: Sage. Retrieved from http://srmo.sagepub.com/view/the-sage-handbook-of-action-research/d24.xml

UNESCO (2008) Education and the Search for a Sustainable Future, Policy Dialogue 1: ESD and Development Policy. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001791/179121e.pdf.

Van de Ven, A.H. (2007). Engaged Scholarship: A Guide for organizational and Social Research. London: Oxford University Press.

Van de Ven, A.H. (2011). Engaged scholarship: Stepping out. Business Strategy Review, 2, 43-45.

Weisbord, M. R. (2012). Productive Workplaces: Dignity, Meaning, and Community in the 21st Century (3rd Ed.). New York: Pfeiffer.

Zander, R.S. & Zander, B. (2002). The Art of Possibility: Transforming Personal and Professional Life. New York: Penguin.

Endnotes

[i] These adult learning principles were articulated by these leading experts: John Dewey (1997), Kurt Lewin (1997), David Kolb and Ron Fry (1975), David Kolb (1983), Malcolm Knowles (1984), Stephen Brookfield (1984; 1991), Jack Mezirow (1990; 1991; 2000a; 2000b; 2009), Robert Kegan (1982); Paulo Freire (2005); Myles Horton and Paulo Freire (1990), Chris Argyris (1991; 1999; 2008), Donald Schön (1986; 1997), Chris Argyris and Donald Schön (1992), Ron Short (1998), Edgar Schein (1995; 2013), Peter Senge (2006), Dorothy MacKeracher (2004); Otto Scharmer (2009), and Marilyn Taylor (2011)

[ii] The authors wish to acknowledge that these principles are the collaborative work of all SoLS faculty and staff. While we have added the literature to support and explain these concepts, the principles themselves came from our discussions of what we valued and believed about leadership.

[iii] Examples used by permission.

About the Authors

Brigitte Harris is passionate about educating leaders who can make the world a more compassionate and better place. She characterizes her doctoral studies (Ph.D., Ontario Institute for Studies in Education) as a compelling, engaging and ultimately transformational journey. She believes graduate education needs to have those qualities, which is why she loves the work of the School of Leadership Studies at Royal Roads University. Her research interests include qualitative research methods, especially action research, narrative inquiry and arts-based research, learning and teaching in higher education, workplace and professional education, and leadership in healthcare settings. Harris is Associate Professor and the Director of the School of Leadership Studies at Royal Roads University. As a scholar-practitioner, she has led large-scale program evaluations in post-secondary programs, the private sector, and government contexts. She has also used traditional and non-traditional research methods, evaluation, and engagement strategies to lead organizational transformation.

Brigitte.3harris@royalroads.ca

http://www.royalroads.ca/prospective-students/programs/leadership-studies

Niels Agger-Gupta has been a core faculty member in the School of Leadership Studies at the Royal Roads University since 2007, and was the MA-Leadership Program Head between 2010 and 2013. He has been a consultant and researcher specializing in organizational change, program evaluation, action research, world café, and cultural and linguistic competency in health care. Niels edited the LA County Department of Health Services Cultural and Linguistic Competency Standards (2004), and co-authored “Language Barriers in Healthcare Settings: an Annotated Bibliography of the Research Literature,” and “The California Standards for Healthcare Interpreters,” both published by The California Endowment. As Scholar-Practitioner with Fielding Graduate University’s Institute for Social Innovation, Niels designed, implemented, and evaluated Appreciative Inquiries with Santa Barbara non-profit organizations. Dr. Agger-Gupta holds a Ph.D. in Human and Organizational Systems and an M.A. in O.D. from Fielding Graduate University, in Santa Barbara, California.

Thank you for this in depth story of the transformation that developed the Leadership program today. I look forward to sharing my voice and perspectives as I transform my personal leadership skills.

Thank you for sharing this inspiring account of the journey to create an enriching MAL program.

I am inspired and moved with emotion and excitement and look forward to furthering my knowledge, growing and learning more about myself and how to engage the world on a deeper level in order make a positive impact to everyone I encounter.

Sincerely,

Celestine.

Thank you for this! I was struck by the powerful transparency of these insights. It seems like the volume of and quality of meetings here really made the difference. In my experience, it takes vulnerability and time to move from strategic planning as an event to strategic planning as a practice.