Exploring the Pathways to Postconventional Personality Development

Angela H. Pfaffenberger

Angela H. Pfaffenberger

Angela Pfaffenberger

Abstract

Abraham Maslow originated the notion of self-actualization over 50 years ago. However, very little research has emerged addressing the question of how individuals can progress to advanced stages of development. Past research has shown that the majority of adults fail to achieve the most advanced stages of personality development and that such development remains rare in contemporary cultures. This article presents the results of a grounded theory study that enrolled 22 international participants who had reached the highest stages of personality development as defined in Loevinger’s (1976) theory of ego development. The guiding question for our research was what factors facilitate such exceptional development in adulthood. Written narratives and semi-structured interviews formed the basis for a grounded theory analysis. The findings support the conclusion that persons at postconventional stages of development define development and view their growth paths in significantly different ways than persons in the conventional tier of development. A development model based on an interaction of diverse factors, such as cognitive complexity, inner awareness, and intention to grow with concomitant commitment offers the most parsimonious explanation for advanced development. Understanding the complexity of high stage development may offer a pathway to fostering such development and appraising correctly what type of person is most likely to progress.

Abraham Maslow’s theory of self-actualization was operationalized in subsequent decades by the structural-developmental theories of Kohlberg (1969) and Loevinger (1957). Maslow’s theory of self-actualization delineated how individuals progress through a series of invariant, hierarchical stages towards increasing maturity. Consistent research has shown that the overwhelming majority of adults in contemporary culture fail to progress to advanced development, which could potentially bring significant personal and professional rewards. Our empirical research intends to increase our understanding of the developmental processes that lead to the highest stages. We identified 22 high stage individuals and focused on the participants’ interpretations of important activities and facilitative life events, as well as the nature of the identities they created for themselves, and the social contexts that promoted advanced development. A better understanding of the interaction of person, process, and context variables will hopefully lead to successful interventions and educational efforts that facilitate such development.

Loevinger’s (1976) theory of ego development presented the conceptual framework for the study. Of all the stage theorists, only Loevinger focused on personality as a whole, combining aspects of conscious preoccupations, motivation, impulse control, and interpersonal attitudes into a complex matrix of personal and social integration. Loevinger delineated nine progressive stages that are sorted into three tiers, Pre-conventional, up to stage 3, Conventional, stage 4 to 6, and Postconventional stage 7 and above. Pre-conventional development is marked by low impulse control and fear of punishment, whereas conventional development is characterized by social conformity and respect for rules. Self-Aware, stage 5 of development, is the modal stage of development for adults in industrialized societies. As an individual moves from Pre-conventional development towards conventional development they need to understand personal differences and become more tolerant in order to achieve Self-Aware.

With the help of a college education, individuals frequently interiorize ethical standards and learn to value long-term goals, the hallmarks of stage 6, Conscientious, the final stage of the conventional development. It appears that about 80% of the population functions consistently at the preconventional and conventional levels. Development to Postconventional stages does not appear to be easy. The following stage 7, Individualistic, requires significantly greater sophistication and psychological mindedness. A person needs to understand that behavior is situated and that individual differences make it hard to proscribe rules and judgments. At the stage 8, Autonomous, individuals embrace postmaterial values and become orientated towards self-expression and authenticity. This stage corresponds approximately to Maslow’s (1954/1970) notion of self-actualization. Loevinger remained vague about even more advanced stages of development, pointing out that the available pool of participants at the highest stages was extremely limited in all known studies. Cook-Greuter (1999) and Hewlett (2004) explored Post-autonomous development. According to Cook-Greuter, stage 9, Construct-aware, is marked by an interest in the process of meaning making, as well as the way in which we arrived at our sense of self and outer reality. At stage 10, Unitive, individuals maintain a present-centered flow of awareness and tolerate ambiguity with ease.

A few studies have explored variables that are associated with stage progression (Helson & Srivastava, 2001; Pfaffenberger, 2005; Westenberg & Block, 1993). These studies pointed to a diversity of factors that are associated with developmental advances, including meditation, psychotherapy, formal education, complexity of work, and dispositional factors, such as giftedness, ego resilience as well as openness to experience. However, most of this research neglected to take into consideration that development to the postconventional tier appears to be discontinuous, because it is not normative and social supports are absent in the normative culture. Very few research projects have completed a separate data analysis for participants at the Postconventional tier (Helson, Mitchell, & Hart, 1985; Hewlett, 2004; Stitz, 2004; Vaillant & McCullough, 1987). Previous researchers have explored what persons at postconventional stages are like, with regard to their meaning making strategies and relational capabilities, but none of the previous researchers had attempted to understand how and why such development may unfold. In short, practical applications of the developmental model at higher stages have been difficult, because an interested practitioner is looking at independent factors that can hardly be coordinated in a meaningful manner. Our research is aspiring to move from variables to interactions and processes that will allow more meaningful interventions in educational, therapeutic, or corporate settings.

Our Research Project

Grounded theory as a method is ideal when we seek to move from individual, subjective perspectives to a more generalized understanding of human processes.

We set out to hear the perspectives of persons at higher stages about their personal journeys and what facilitated them, and use that data to develop a theory of how development to higher stages unfolds. We recruited participants through online invitations that asked them to complete Loevinger’s Sentence Completion Test. We attempted to obtain a sample that showed diversity in terms of nationalities, ethnicities, religious and political orientations, educational achievements, gender and age. However, due to the difficulties of finding a sufficient number of participants, all high-scoring individuals who were interested, became participants. Regrettably, all participants were Caucasians from industrialized nations. In total we identified 22 postconventional participants with 8 nationalities, between the age of 25 and 74; 12 were male and 10 female. The demographics of the postconventional participants are shown below.

Table 1

Postconventional Participants’ Ego Stage Scores

|

7/ |

8/ |

9/ |

10/ |

|

|

Number of |

5 |

13 |

3 |

1 |

Table 2

Postconventional Participants’ Ages

|

20-29 |

30-39 |

40-49 |

50-59 |

60-69 |

70-79 |

|

|

Number of |

2 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

Table 3

Postconventional Participants’ Levels of Education

|

Less than BA |

BA |

MA/MS |

Ph.D. |

|

|

Number of participants |

5 |

3 |

10 |

4 |

Table 4

Postconventional Participants’ Nationalities

|

U.S./Canada |

Europe |

Australia |

|

|

Number of participants |

15 |

6 |

1 |

Preliminary data analysis suggested that it would be helpful to interview a closely matched sample. In addition to the 22 postconventional participants, 6 conventional participants were subsequently chosen as a control group. All participants were asked to write narratives or participate in interviews that were completed in-person or on the phone. The interviews were semi-structured. Emphasis was placed on gaining an understanding of what the participants thought helped them grow as a person, what were their values and goals, and what was their experience of the growth process. The participants were encouraged to choose their own subject matter and talk about what appeared most relevant to them. Follow-up probes clarified a few specific issues. The interviews were transcribed and combined with the written narratives; about 800 pages of text were obtained in this manner over a period of two years. Following the data analysis, we performed so-called member-checks, whereby we solicited commentary from the participants about our interpretation.

Findings

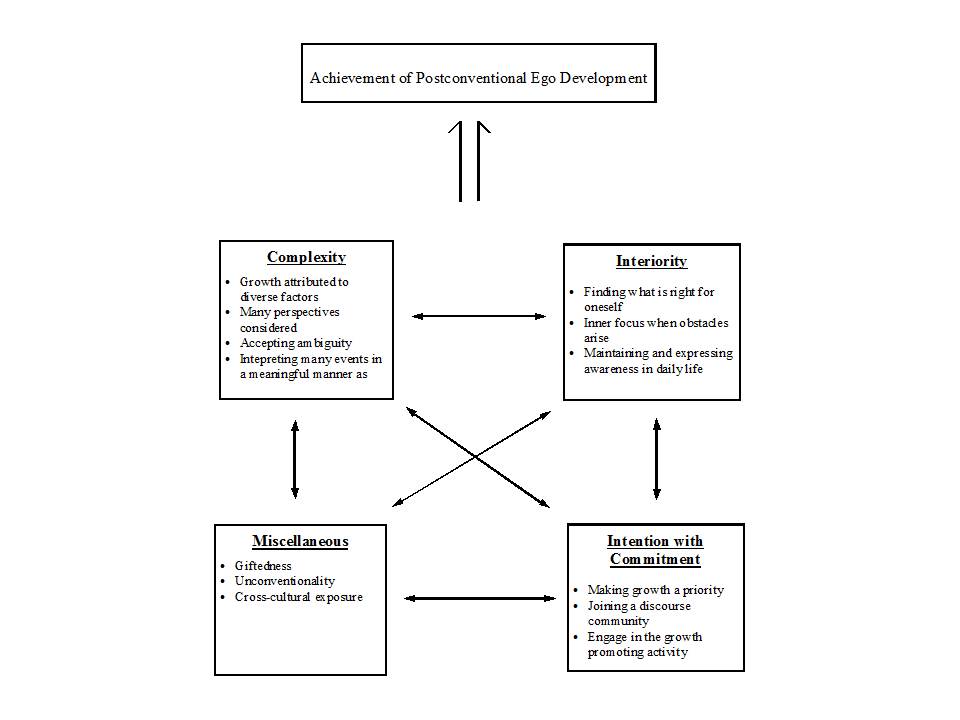

Persons at postconventional stages of development defined development and talked about their growth in significantly different ways than persons in the conventional tier of development. A number of different aspects distinguished reliably between postconventional and conventional participants’ narration of growth stories. Three major themes emerged: complexity of narrative, interiority, and intention with commitment. Minor elements, meaning those that were not as universally true but still robust in the data analysis included giftedness, unconventionality, and cross-cultural exposure. Below each one of these aspects will be discussed in detail, and the way they interrelate will be considered. A schematic representation of the findings is given in the Appendix.

Complexity. The most noticeable aspect in the narratives and interview materials was that as the ego stage increases, the complexity of the story increases. The complexity of the story appears to be linked to the complexity of cognitive-emotional integration. Conventionally scoring participants told stories that had significantly fewer elements and the aspects that were included showed less variety. For example, one conventional participant focused in the interview almost exclusively on his struggle with maintaining sobriety and the positive changes that resulted from that experience. In contrast, postconventional participants told complex stories that integrated many different aspects. The diverse elements were linked coherently to the growth process and are interpreted in this manner. For example, Liam (participant names have been changed to respect their privacy), aged 25, a Stage 9 participant, talked about joining a men’s group where he learned about group processes, about growing up without formal schooling in an artists commune in California, and about living on a farm in New Zealand, where he connected with the land and acquired skills in farming. In addition to the complexity of the narrative itself, postconventional participants also expressed their views in a significantly more complex ways, meaning any given experience was seen as having multiple perspectives that needed to be taken into consideration. Within the postconventional tier of development, complexity increased with every stage.

The finding about complexity was the most robust in the study and was indeed one of the leading indicators that discriminated reliably between conventional and postconventional narratives and interviews. Higher development appears to be linked to a willingness to fully participate in a wide variety of activities, the ability to see those activities and events as beneficial opportunities for growth, and an ability to make finely shaded differentiations in one’s experience. Postconventional participants exhibited a willingness to accept the complexity and the often-accompanying ambiguity in their lives. Fiona, a 39-year-old lawyer from Britain concluded her written narrative:

I went through a period where I adopted values, they became my own and then later I realized the limitations of values (and especially values statements) and now prefer to talk about what makes sense for me. I don’t have many answers any more – the world is such a complex place. I seem to be increasingly thin skinned and often filled with great sadness. Compassion for others is often what makes most sense. My relationships are important to me, and maintaining my integrity at work. I would like to do more, change more, but the opportunity to do so has not come yet, and I am not sure what I would stand up for any more.

Interiority. In addition to complexity of the growth story, the main element that reliably distinguished between conventional and postconventional participants was interiority. The narratives of postconventional participants showed a high degree of introspection and inner awareness. An inner orientation was often expressed in vivid descriptions of lived experience. Two different aspects will be discussed separately, (1) the need to attune to what is right for oneself and express that consistently in one’s life, and (2) the way external obstacles were approached.

The majority of the postconventional participants talked about exploring what was right for themselves and living a life where their inner awareness was expressed. A frequently emerging theme was that finding this inner congruence between whom a participant was and what the environment demands, was more important than material gains or other conventional achievements. Liz, a 37-year-old graduate student from Britain wrote:

The next experience that shaped me was a voice that told me to return to study – quite specifically nutrition and psychology. I was on the cusp between sleep and consciousness. The voice could have been a dream, an inner suggestion. Whatever it was it brought me out in goose-bumps and I followed it. I completed a postgraduate diploma in psychology and I’m now in my final year of an MSc. I work as a coach and counselor. The significance of this event was the conviction that I had to do something new, to move forward in my life. It is also significant in that I am doing something that I really enjoy, can make sense of my past, and help others to move forward and make the most of their lives.

The participants differed in regard to how much difficulty this search entailed for them. In the stories of postconventional participants existential themes often surfaced, such as understanding that life is finite and that you need to make a choice about what to do in order to create meaning. The majority of postconventional participants conveyed directly or indirectly that they felt that meaning in life arose from the fact that they explored who they were and what their contribution consisted of. The stories of conventional participants showed an entire absence of themes in regard to finding one’s inner self and attempting to express that consistently.

A somewhat separate aspect is how the participants talked about external difficulties in their lives. Stories that had no mention of external difficulty were rare underscoring the importance of obstacles in the perceived growth paths of individuals. However, a significant difference between the groups was that conventional participants described almost all their growth as prompted by obstacles, whereas postconventional participants showed more diversity, and often slight incidences could lead to introspection and self-knowledge. Many postconventional participants described specific growth episodes that had no element of external difficulty but instead they talked about choosing to stay with an inner sense of unclarity or discomfort. It appears from the data analysis that a willingness and ability to take an interest in one’s inner process and to sustain this inquiry is what actually increases a persons complexity and leads to a better integration of the self.

When external difficulties arose, conventional participants conceptualized and described the growth as a change in behavior whereas postconventional participants placed greater emphasis on the increase of inner awareness. An example is how one conventional participant described her decision to leave an abusive relationship and become more self-sufficient. In contrast, postconventional participants saw growth as a change in perspective, in self-identity, or in increased awareness. Several postconventional participants also mentioned being prompted by difficulties with their intimate relationships, but they placed impetus for growth on becoming more willing to experiment with previously unfamiliar values and emotions. It appears that personal growth is closely linked to an ability to remain focused on one’s inner experience and to sustain this inner awareness, even when the innermost values and assumptions were questioned. Jackie, a 27-year-old stay at home mother without college degree said:

It feels like the practice that led up to it was really just being willing to ask questions that I don’t find other people ask a lot and to be able to question yourself, question, literally like the basis of all of your thinking and question like, well, why do I react this way… why do I think this way… why do I feel this way… and then retrospectively, looking back… and kind of making the connections to understand at what point those concepts were embedded in me… so that… I then kind of felt that I had a grip on the process and was able to kind of look above, or stand above and look down on myself objectively, somehow.

In regard to inner awareness, an additional aspect that emerged and was representative of only stage 8, Autonomous, and higher was an emphasis on how inner awareness alone is not sufficient, it also needs to be expressed in one’s beingness, integrated in one’s conduct and behavior, and embodied in ones presence. Scott, a 60-year-old management consultant said:

…but where it really shows up is when you go to work. I’m very interested in how you integrate that consciousness into your work life, because there are so many people who don’t. You know, they have some kind of meditative experience, and they use it as a kind of soothing mechanism or method of stress reduction. When you do that it doesn’t really integrate very well… you just say, I have this nice environment where I can still my mind, and then I can always go there when things get tough. The question is, how can you have those qualities available to you when things are tough and you are in the middle of it?

In sum, postconventional participants have well differentiated inner lives. They explore what is right for themselves and strive to express that in their lives. When obstacles arise they maintain an inner focus and interpret the obstacle as a means of increasing their awareness and insight. However, growth was frequently attributed to aspects that were not related to external obstacles. As ego stage increases, individuals seem to place more emphasis on how the awareness is brought to bear on their daily lives.

Intentionality. A consistent theme throughout the postconventional narratives was the expressed valuing of growth, the desire to grow, and the commitment to act on this desire through efforts that often involved persistence, discomfort, and exertion. Simultaneously, there appeared to be a departure from more external, culturally formed values, such as financial success and professional achievement. The intentionality has several aspects that usually occurred in combination, and it appears to be one of the key aspects of understanding higher development.

Postconventional participants value growth and seek it intentionally. To this end, they use a variety of means, such as (1) join a community of likeminded individuals, which is termed here a discourse community, (2) they adopt a consistent theory of growth, and (3) they maintain specific practices that enhance their inner awareness and carry them out consistently for many decades. The community itself appears to fulfill several powerful functions. Although talking about growth has become trendy in the pop-culture and on certain TV shows, our contemporary culture does not encourage and facilitate a deeper exploration of congruence and inner experience. Many postconventional participants talked about difficulties with finding likeminded people and being uninterested in party talk. Joining a discourse community offers a shared value system, as well as opportunity for dialogue and cognitive learning about growth, in addition to emotional support and social engagement. The majority of postconventional participants had well thought out theories about how and why growth occurs, and this question was clearly not something they started to contemplate during or in preparation for the interview. Almost all participants talked about having read specific books about growth and their self-knowledge was often well balanced with theoretical perspectives.

A pointed finding that emerged was that very literal adherence to a specific growth philosophy and practice was typical for Stage 7 participants, meaning the early stages of postconventional development, and it was not at all to be found among the higher stage participants. At Stage 8, Autonomous, and higher, participants still talked about their studies and practices within certain schools of thought, but their views were more differentiated, and there was no unequivocal endorsement of any given group or world view.

The findings suggest that joining and participating in a growth community appears to be instrumental in progressing from Conventional to Postconventional development, but rigid, unquestionable adherence appears to act as an obstacle to further development. Several, but not all, Stage 7 participants held their discourse community to be superior, and saw those views as the only correct ones, such as “growth means understanding egolessness” and “unless you meditate and understand egolessness you have not really progressed in development.” A number of Conventional participants who were on the cusp of the postconventional tier phrased their narrative entirely in the language of their discourse community.

Postconventional participants showed a strong tendency to increase their inner awareness through specific practices and activities. Meditation was the most frequently mentioned activity in this regard, closely followed by psychotherapy, coaching, and the practice of martial arts. The aspect of maintaining a spiritual practice that promoted growth and increased the inner awareness was almost universal, and several participants spoke about the difficulties and the perseverance required. Although participants had often devoted a great deal of energy to their paths and endured sacrifices, they voiced appreciation for those experiences and clearly derived meaning from them. Meditation was a pronounced theme in many interviews, even among those participants who responded to invitations on management listserves, but it was not a universal theme.

To sum up, postconventional participants expressed a great deal of intention about their growth and described a plethora of activities they engaged in to achieve that growth. The most widely shared themes were the joining of a discourse community of persons with similar interests, becoming informed about the growth process, and carrying out practices that they believed to be growth enhancing.

Miscellaneous element. In addition to the three main aspects of complexity, inner awareness, and intentionality, several aspects emerged in the data analysis. Subject matter by itself was not a good indicator of ego stage and did not differentiate reliably between conventional and postconventional participants. The most frequently mentioned theme without prompting was the participants’ intimate relationships, with emphasis on the benefits of close engagement and threatened dissolution of the relationship being equally likely to be discussed. Conventional and postconventional participants were equally likely to mention their relationships. Although themes were not a good indicator of higher development, some exceptions emerged, including giftedness, self-employment, unconventionality, and cross-cultural experiences, with the latter two often interwoven. Idiosyncratic aspects that emerged in the interviews will be discussed last in this section.

A very significant number of participants mentioned early academic interests, significant achievements in academia, such as awards, and Mensa memberships. Although the fact that the group of conventional participants is rather small, the evidence in the data is tentative, but statements about early intellectual interests were unusually frequent among the postconventional participants. Considering the predominance of signs of giftedness, it was a surprise that only two of the postconventional participants mentioned creative interests or any aspect of the creative process contributing to their growth.

Regardless of educational attainment, postconventional participants seem to be inclined towards self-employment. They appeared highly motivated and took their livelihood seriously. They often stated that the disadvantages of self-employment, such lack of benefits and less security were outpaced by the prospect of being one’s own boss and not needing to accommodate constraints. Although management professionals were frequent among the postconventional participants, not a single one of them maintained a regular position in a corporation. Several of them mentioned that the importance of appropriate livelihood needs to be balanced with other aspects in life, such as attending retreats and spending time with their families.

The subject area of traveling or working abroad, of reflecting on the constructed nature of consensual social reality was prominent. Many participants seemed to be educated about social construction and critical theory. Cross-cultural experiences seem to present an opportunity to ground this knowledge in a personal, lived experience. Furthermore, it appears that postconventional participants had unusually rich and often unconventional lives. Unconventional choices were often tied to cross-cultural experiences. The participants viewed their diverse experiences in terms of how they provided growth for them. Examples abound. Scott, a Stage 10 participant, talked about living in an ashram with an Indian teacher for 12 years. Upon the encouragement of his spiritual teacher he entered into an arranged marriage with a woman he had met only four days earlier. 33 years later he was clearly enthusiastic about this relationship although he talked about having worked through significant emotional issues in order to sustain his marriage. Liam # 531, age 25, a stage 9 participant, talked about entering a 90-day meditation retreat in Myanmar.

I had to wear robes all the time and so a sense of identifying with the person I know myself to be was kind of challenged with that, surrounded by people that looked the same, with the idea of doing the things I was doing, not speaking, and getting lots of gifts and support from people that are very poor. They would give their food, we would have to go beg for our food, and they would give us their food, which they don’t have very much of, so it was an enormous privilege and it was put in that light, that it was a precious opportunity.

A final element that emerged, particularly from the narrative analysis, was that many themes were highly idiosyncratic, meaning they were only mentioned once and did not fit any category without pushing the boundary of the interpretation. For example, Roger talked about a sense of fulfilling his destiny. David, a 60-year-old professional healer, wrote about experiencing a sense of protection when he assisted comrades during combat in Vietnam. Liam mentioned a near death experience in childhood and also discussed not receiving formal schooling and consequently having being unable to read and write until he was 10 years old. The diversity of choices, life paths, and experiences described was striking. In short, it is important to keep in mind that clear aspects emerged that showed commonalities, but at the same time many participants also included elements that could not be sorted into any category. Postconventional growth emerges from this study as a highly individualized process.

Several themes were hard to interpret because of the small sample. An example is that two women, 20% of the postconventional females, talked about positive aspects of serving in the armed forces. This came as a surprise because postconventional individuals tend to reject environments with strong demands for conformity. Both women mentioned that it offered them an opportunity to develop leadership qualities. However, it is hard to know if this is a chance finding or if there is a developmental benefit to military service for females that would be worth exploring further.

Most participants mentioned their childhoods without being prompted. However, no themes emerged. Conventional childhoods, good attachment, and social privilege seem to be mentioned about as frequently as unstable childhoods, incomplete families, unconventional parenting, or difficult emotional experiences. Significant trauma was infrequent. It was usually mentioned in the context of how the participant had been able to work through it later in therapy and gained insight.

A theme that was difficult to interpret was the role of peak experiences. The term peak experience is used here as an umbrella including all experiences of non-ordinary awareness and knowing. Wilber (2006), Marko (2006), and Maslow (1954/1970) all point to peak experiences and altered states as growth inducing and a hall mark of higher development. However, in this study no clear data interpretation emerged. When asked about experiences that were growth promoting, the majority of the postconventional participants nor any of the conventional participants mentioned peak experiences. In a follow-up probe, they were specifically about peak experiences. The postconventional and conventional participants readily described them. The postconventionals were more likely to offer detailed descriptions and made growth attributions for those experiences. The most frequently mentioned peak experience was spontaneous, profound meditative stabilization. However, for a minority of postconventional participants who did mention altered states, this was clearly an important aspect of their developmental paths, and it was accorded significance. It is possible that within the overall group of self-actualizers there are subgroups, and persons who experience peak experiences as especially important and growth promoting form such a subgroup. An alternate explanation is that peak experiences are especially important at the beginning of the growth process, when a person first understands that consensual reality is just one version of interpreting reality, but those experiences may diminish as the individual gets used to the process of growth.

Dissonance with cultural values was not a pronounced theme. None of the conventional participants mentioned it, nor did a significant percentage of postconventionals mention it.. It appears that when a person first departs from conventional norms which focus on achievement and success, and start to embrace a more inner, self-directed form of meaning making, they experience being out of sorts with the dominant culture, but over time they get used to that feeling and it no longer penetrates into their conscious awareness. Joining a discourse community seems to help individuals to normalize the experience of having different perspectives and adhering to beliefs that are not shared universally.

What role does spiritual development and practice play in the progression towards postconventional stages of development? It appears that inner directedness and intention to grow are the predominant aspects. In our contemporary culture, there are limited means and ways for intentional psychological growth available, especially outside of urban centers in California. Spiritual communities and the practices they offer present venues which a person may use to further their development. However, we cannot conclude that they are necessary or superior because we have not compared them to other hypothetical tools.

An interesting point of consideration is why certain growth devices appeared to work for some individuals but not for others. It appears that no specific aspect is in itself sufficient. The above discussed points, complexity, inner directedness, and intention with commitment, do not exist independently of each other or in an additive manner. Rather, it appears that those aspects need to be present and interact with each other in a beneficial manner. Choosing membership in a growth community clearly interacts with the aspect of inner awareness. Within the group of the conventionally scoring participants, the author intentionally interviewed members of discourse communities, including her own community, to differentiate between acquired growth talk and genuine development. Conventionally scoring individuals in this group had also studied growth philosophies and engaged in long-term meditation; however they expressed very little inner awareness. Apparently, a person can value growth and practice meditation with a community for many years and not progress to higher stages of development. Other aspects need to also be present, and most paramount seemed to be inner awareness and cognitive complexity expressed as a well-differentiated attitude towards the practice, and towards one’s own growth and beliefs.

A final question for us was: What themes are absent, what was not talked about? Although participants mentioned hardship, it was the kind of hardship that was workable for them, suggesting that challenges are beneficial if they are within the person’s coping ability. Among the postconventional participants, overwhelming trauma, such as becoming disabled, being a crime victim, severe poverty, having an ongoing addiction, or mental illness was not mentioned, neither was any deviant, negatively sanction behavior, such as being convicted of a crime. Postconventional participants did not have charmed lives, but they displayed positive emotional and mental skills and appeared free from regret, resentment, cynicism, and anger. The principal researcher was struck throughout the process of how genuinely helpful and likeable the participants were. Many had a wonderful sense of humor, as they came across as interpersonally warm and possessing great social skills. It was rare that everyone responded to requests from the researcher.

The limitations of the study are related to: (1) the research design that was used, (2) the sampling procedure, and (3) instrumentation. The research strategy and design of the study were based on the assumption that individuals have insight into what helps them grow, which may not necessarily be the case. However, no claims were made that this inquiry was exhaustive and covers all aspects of growth. This study was exploratory and the design was chosen in part because few other alternatives were feasible. The number of available postconventional participants remained too small to consider a quantitative evaluation based on questionnaires. Qualitative research usually engages a small number of participants, which limits generalizations that can be made to the population at large. Limitations were also created by the sampling procedure. Most or all participants belonged to the dominant Anglo-Saxon culture and had a middle class or better upbringing. Persons with more social advantages and advanced educational degrees were overrepresented. Additional limitations were imposed by the choice of test. In light of the fact that hundreds of individuals were tested in order to find a few high scoring ones, Loevinger’s SCT was one of a very few available instruments that fit our requirements. The SCT does not measure adjustment, mental health, or subjective well-being. As other authors (Helson & Srivastava, 2001) have pointed out it might be a specific interpretation of what is desirable in adulthood.

Opportunities for new directions for research abound, and just a few will be mentioned. Hewlett (2004) and Marko (2006) have suggested that there might be different pathways to higher development for different types of personalities. Our project is mostly supportive of this assumption, and this subject would be worth exploring if we wanted to succeed in designing interventions that promote development.

Another question concerns the longitudinal stability of postconventional development. It appears entirely possible that a significant percentage of the population experiences episodes of Postconventional functioning, but we cannot perceive this occurrence we usually only test participants once and then conclude if this is a Conventional or Postconventional person. Studies that demonstrated the longitudinal stability of ego stages usually involved a high percentage of conventional participants, and we do not know if these findings apply to a postconventional sample. The idea of temporary postconventional functioning has a strong intuitive appeal to the principal researcher. Temporary postconventional functioning would most likely take place when challenges and complexity increase, and support is available, such as while being in graduate school, after assuming a new work position with greater demands, or during time spend abroad. It is possible that individuals function at the advanced level temporarily but then settle back into a more comfortable conventional tier because no environmental supports are available. It would be interesting to explore why some persons maintain their advanced stage long term and others do not.

So far, no study has explored the role of generativity in higher development and the social contributions of high stage individuals. Postconventional individuals may have a different understanding of what generativity actually is, and how they feel it is relevant to them. Maslow (1954/1970) suggested that self-actualizers have a project beyond their personal gain that they work towards tirelessly. It seems intuitively correct to assume that they are dedicated because of their advanced development, but it is also possible that the challenges of the project promote their development, meaning because they care profoundly about a given cause they have to explore many venues to achieve their goals.

The exploration of generative understanding and expression in higher development appears as an extremely promising and rewarding project. Our study suggests that generative concerns were common, but generative engagement in terms of activism was not. At one point the principal researcher intentionally tried to recruit social activists who scored at Postconventional level and was unable to do so, which suggests that Postconventional individuals are not drawn to social and political engagement in its current form. This gives rise to the question of what would be Postconventional social engagement.

The current study suggests that higher development is not without its challenges. Hewlett (2004) offered some rudimentary ideas about the problems persons at the highest stages encounter, but by and large this is also an unexplored area of research. Postconventional development, and the contributions individuals at that stage of development can make on a societal and cultural level clearly is a promising and wide-open field.

References

Cohn, L. D. (1998). Age trends in personality development: A qualitative review. In P. M. Westenberg, A. Blasi, & L. D. Lawrence (Eds.), Personality development. Theoretical, empirical, and clinical investigations of Loevinger’s conception of ego development (pp. 133-144). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cook-Greuter, S. (1999). Postautonomous ego development: A study of its nature and measurement. Dissertation Abstracts International, 60/06B. (Pub. No. AAT 9933122). Full text retrieved from Proquest/UMI database on 11/08/03.

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 215-229.

Helson, R., Mitchell, V., & Hart, B. (1985). Lives of women who became autonomous. Journal of Personality, 53(2), 258-285.

Helson, R., & Srivastava, S. (2001). Three paths to adult development: Conservers, seekers, and achievers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(6), 995-1010.

Hewlett, D. C. (2004). A qualitative study of postautonomous ego development: The bridge between postconventional and transcendent ways of being. Dissertation Abstracts International, 65/02B. (Pub. No. AAT 3120900). Full text retrieved from Proquest/UMI database on 05/05/04.

Hy, L. X., & Loevinger, J. (1996). Measuring ego development (2nded.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive developmental approach to socialization. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp.348-480). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Loevinger, J. (1998). Reliability and validity of the SCT. In J. Loevinger (Ed.), Technical foundations of measuring ego development (pp. 29-41). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Manners, J. & Durkin, K. (2000). Processes involved in adult ego development: A conceptual framework. Developmental Review, 20, 475-513.

Manners, J. & Durkin, K. (2001). A critical review of the validity of ego development theory and its measurement. Journal of Personality Assessment, 77(3), 541- 567.

Manners, J. Durkin, K., & Nesdale, A. (2004). Promoting advanced ego development among adults. Journal of Adult Development, 11(1), 19-28.

Marko, P. W. (2006). Exploring facilitative agents that allow ego development to occur. Dissertation Abstracts International, 60/06B. (Pub No. AAT 3217527). Retrieved December 28, 2006, from ProQuest/UMI Dissertations and Theses Database.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper and Row. (Original work published in 1954.)

Pfaffenberger, A. (2005). Optimal adult development: An inquiry into the dynamics of growth. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 45 (3), 279-301.

Stitz, J. (2004). Intimacy and differentiation in couples at postconventional levels of ego development. Dissertation Abstracts International, 65/02B. (Pub. No. AAT 3153925 ). Full text retrieved from Proquest/UMI database on 03/05/06.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vaillant, G. E., & McCullough, L. (1987). The Washington University Sentence Completion Test compared with other measures of adult ego development. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1189-1194.

Westenberg, P. M., & Block, J. (1993). Ego development and individual differences in personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 792-800.

Wilber, K. (2006). Integral spirituality. Boston: Shambhala.

About the Author

Angela Pfaffenberger, Ph.D. has a professional back ground as an acupuncturist and psychotherapist. She also has research interests in personality theory, humanistic psychology, and integral theory. She has been engaged in the study of self-actualization and optimal adult development and has repeatedly published her findings in peer reviewed journals. In her spare time she contributes to dog rescue efforts and works as a glass artist. Currently maintains a private practice in Salem, Oregon. Angela enjoys discussion and dialogue about adult development and can be contacted at angelapfa@comcast.net

Appendix

A Model of Adult Development to Postconventional Stages

A Model of Adult Development to Postconventional Stages

Table 1: Postconventional Participants’ Ego Stage Scores

|

7/ |

8/ |

9/ |

10/ |

|

|

Number of |

5 |

13 |

3 |

1 |

Table 2: Postconventional Participants’ Age

|

20-29 |

30-39 |

40-49 |

50-59 |

60-69 |

70-79 |

|

|

Number of |

2 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

Table 3: Postconventional Participants’ Levels of Education

|

Less than BA |

BA |

MA/MS |

Ph.D. |

|

|

Number of participants |

5 |

3 |

10 |

4 |

Table 4: Postconventional Participants’ Nationalities

|

U.S./Canada |

Europe |

Australia |

|

|

Number of participants |

15 |

6 |

1 |