Andrew Munro

“Decisions taken today are driven by our visions of tomorrow and based on what we learned yesterday.”

– Professor Bruce Lloyd

Executive Summary

The concept of wisdom is making a comeback (1). Following a period of business folly and fiasco, there is a growing realisation that classic competency frameworks fail to integrate fully the cognitive, affective and motivational dynamics of sustainable leadership. Abandoned some time ago as a quaint but non-scientific construct, wisdom is now regaining recognition as a key component of leadership. This article summarises the “seven pillars” of wisdom (2) and explores one pillar; “time perspective” to provide fresh insights to highlight different manifestations of foolish and wise leadership.

1. Wisdom: an Overview

In her analysis of “bad leadership”, Barbara Kellerman (3) distinguishes between incompetent and unethical leadership. No doubt moral bankruptcy has and will continue to be a factor of destructive leadership. More often, however, bad leadership is foolish leadership, a leadership outlook and operating set of priorities without the essential element of wisdom. Although we can draw on constructs that appear on the surface scientific, like cognitive complexity, emotional intelligence or learning agility, we propose that we access an established tradition and utilise the concept of wisdom for a better understanding of the dynamics of leadership that underpin long-term success and help explain the reasons for derailment and failure.

Wisdom is interpreted in various ways (4) reflecting a range of different perspectives from theorists and researchers, but typically incorporates such themes as: “practical knowledge” and the exercise of an “uncommon degree of common sense”; cognitive mastery and a kind of meta-intelligence that knows how to think; exceptional judgement that identifies and resolves the “wicked problems”; a special type of insight that has the penetration to “see beyond illusion”; or more broadly, a set of values and attitudes about life and how it should be lived.

What is remarkable has been the neglect of wisdom in the academic literature. Intriguingly the research enterprise, beginning in the 1980s, wasn’t triggered by any leadership thinker or practitioner, but by gerontologists looking at the aging process, and their interest in what was positive about aging. More recently the positive psychology movement (5) has raised awareness of the dynamics and outcomes of wisdom as a key domain of “strength”. The research now incorporates three strands (6):

- Folk theories to evaluate what the general public think about wisdom and the attributes they associate with wise individuals

- Wisdom performance and the study of individual performance in tackling wisdom-based problems

- Survey measures to map out a coherent and robust framework for the assessment and development of wisdom

But it still early days in the research enterprise, and relatively little is known about the impact of wisdom on leadership effectiveness and organisational success.

2. The Seven Pillars of Wisdom

“Wisdom hath builded her house, she hath hewn out her seven pillars.”

– Proverbs 9:1

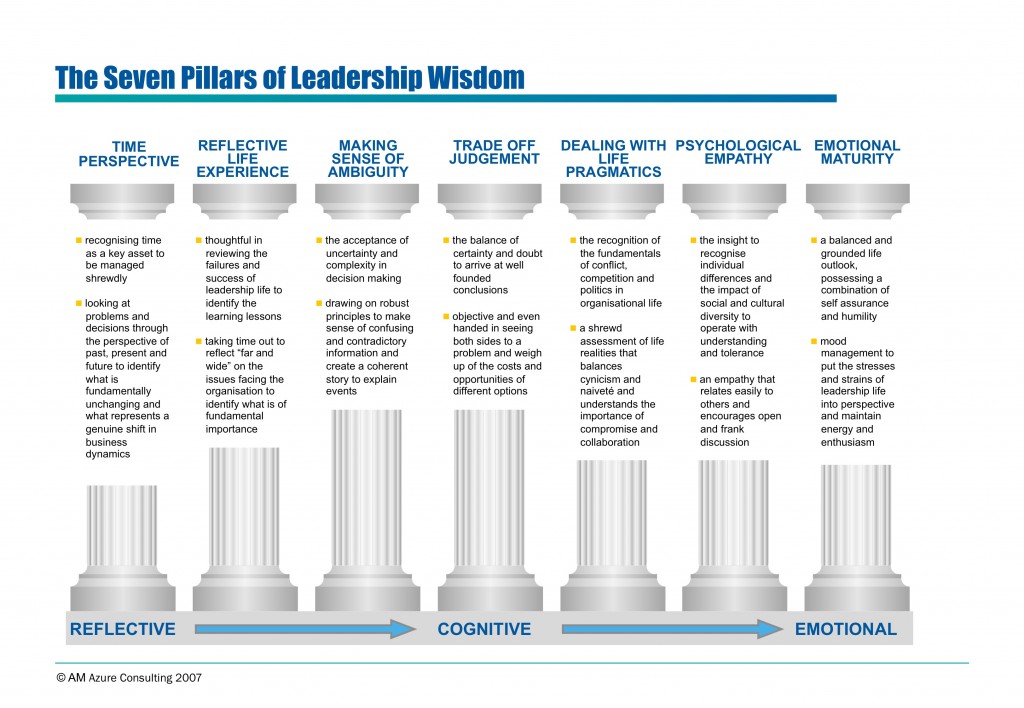

The “Seven Pillars” of wisdom is our attempt to outline a model that incorporates the spectrum of reflective, cognitive and emotional elements that integrate “mind and character” in the development of wisdom. Within this framework wisdom is not a unitary construct but emerges from the interaction of seven components, with all seven factors required for the full and consistent application of wisdom. Specific strengths in any one area do not compensate for a shortcoming within another pillar.

At one level this framework is a blueprint to inform the criteria applied in talent and succession management reviews and appointments decision-making to establish a more discerning evaluation of current and emerging leadership. Here the focus is on encouraging organisations to look beyond the “usual suspects” – often those individuals skilled in self-presentation and upwards management – to identify those individuals with the qualities that underpin executive wisdom. Here it should be noted that wisdom is not always the most valued or popular organisational attribute. It is wisdom that asks awkward questions, expresses doubt and misgivings, looks long-term rather than applies short-term expediency, ignores the trivia, and doesn’t waste energy on self serving, back covering exercises. Wisdom then may not necessarily be the smartest career tactic within some organisations, and wisdom may be a neglected priority for executive development.

At another level this framework can be utilised to create practical tools to support leadership assessment and development (e.g. interview protocols, situational judgement tests, experience maps to guide career progression). We are currently piloting two formats, a self report measure and a 360 feedback application (7), and initial findings are encouraging with, for example, correlates between individual perceptions and line management, peer and team member assessments of capability in managing cultural diversity, a challenge that requires in no small measure, practical wisdom (8).

3. The First Pillar of Wisdom: Time Perspective

“Leadership involves remembering past mistakes, an analysis of today’s achievements, and a well grounded imagination in visualising the problems of the future.”

– Stanley Allyn

If we are constrained by our past, caught up in the pressures of the present, or uncertain about our future, it is difficult to see how we can exercise wise leadership. Time Perspective is that pillar of wisdom which involves maturity of thinking about the past, present and future (9). We can be connected to our past seeing it as a source of valuable experience and learning; or resentful about its impact, or nostalgic for happier times. In the present, we can operate in the current flow optimising our enjoyment of the present; or under siege and avoiding pressing realities, or simply living for the moment. Are we preparing to build a better future; or fearful of what lies ahead, or fantasising about unlikely possibilities?

These stances, towards the past, present and future suggest different leadership outlooks, either operating with maturity and wisdom, or with immaturity and distorted priorities.

Leadership as Connected to the Past

Carly Fiorina, an experienced AT & T and Lucent Technologies executive, entered Hewlett Packard in 1999 with a clear mandate: initiate the kind of change to revive the electronics giant, which despite its stellar track record of engineering innovation and progressive employee practices, was now slumbering. An aggressive push to move jobs overseas with extensive lay-offs was never going to be popular with the workforce. And masterminding the merger with Compaq was always going to meet opposition from the families of the founders who sat on the Board. In 2005 Fiorina was fired.

Maybe it was the replacement of founder Dave Packard’s “11 simple rules” with Carly’s 12 rules of the garage – the outcome of a weekend leadership brainstorming session – however that symbolised the problem. For Fiorina the famous HP Way was an “anachronism of a different and slower time”. Maybe. A connected leader would have been able to understand the fundamental dynamic of trust within the HP Way, and found ways to engage and revitalise that trust.

The mature outlook is that the past may foreshadow the future. This isn’t leadership that looks back with longing to better and happier times. Neither is it a pattern that is battle fatigued and scarred by past failures and now cynical about what is possible. It is the leadership mindset that recognises the importance of continuity from the past to the present and future. This is a leader with judgement who understands the enduring principles of success and failure and is grounded in the realities of business competition, and the dynamics of organisational culture, social interaction and human nature. As Jeff Bezos of Amazon observed: “There’s a question that comes up very commonly: “What’s going to change in the next five to ten years?” But I very rarely get asked, “What’s not going to change in the next five to ten years?”

Of course organisations need to revitalise and renew themselves, but the connected leader is sceptical of “quick rich schemes” and management fads and fashions. The connected leader is attuned to the business fundamentals that don’t change that much, and how to build on these to bridge the past and future.

Leadership as Resentment about the Past

This is the leader who just can’t let go of the setbacks and disappointments of the past. For the resentful leader the past has become a jailor that keeps them in a prison, constraining their flexibility to think and act strategically. The resentful leader can: sulk about perceived wrongs and injustice (think former Prime Minister Ted Heath) or persevere with the sunk costs of a failing decision, determined to prove that they were right.

Even the most successful leaders can sometimes find it difficult to let go of the past. Jack Welch, CEO of General Electric generally didn’t have any problems about the past. In his early years he sold off “sacred industries” ignoring the critics who claimed he was trampling on GE tradition. But he refused to part with Montgomery Ward, the tired department store. Looking to GE for a cash injection of $100 million to reverse its fortunes, Montgomery Ward came back, and back again, for more funding. To protect an initial investment, GE eventually wasted billions. Jack Welch later admitted that it was his ego that got in the way. He just couldn’t let a past investment fail.

Leadership as Nostalgia about the Past

For some leaders the past was a much happier and enjoyable experience than the challenges they face in the present and the future. The past was a time of achievement. Now is proving much tougher. Now it seems difficult to work out what the problems are, never mind what the solutions might be for today and tomorrow. It’s comforting for them, at least in the short-run, to revisit a strategy that once worked and delivered success. Of course as Marshall Goldsmith points out: “what got us here won’t get us there.” But for the nostalgic leader it’s tempting to remind themselves of what got them here and attempt to replicate their past successes again.

Arguably the story of the falling out of Steve Jobs and John Sculley at Apple was the clash between a leader who looked forward with plans for innovative product development and an executive, who looked back to a career where marketing was the key to business success. Sculley, the former Pepsi executive and mastermind of the brilliant Pepsi challenge, was hired to apply his marketing expertise to the Personal Computer market. During Sculley’s tenure at Apple, Jobs was dismissed. As one analyst commented: Sculley didn’t get the reality that “in the world of technology, innovation trumps all other cards”. It isn’t about shaping perceptions of fizzy drinks; it’s about functionality that works.

Later, with Apple’s share price in sharp decline and posting losses, Sculley was then dismissed. On his return to Apple, Jobs “called in the engineers and placed before them a table of the products which had been in development under the old regime. “What do all these products have in common?” When no-one was able to answer he told them: “They are all worthless.” Jobs was getting ready to reinvent Apple around a new future.

Leadership In Flow with the Present

John Akers, former CEO of IBM, remained stuck in the past of mainframe computing. Whilst the rest of the world was moving towards PCs, unsurprisingly IBM struggled (posting a loss of $8 billion in 1992), and Akers had to stand down. His successor, Louis Gerstner, initially resorted to the classic tactics of sell assets and cut costs, a programme for survival. Astutely observing that “the last thing IBM needs right now is a vision”, Gerstner focused initially on execution, decisiveness and speed to break the grid lock of the IBM bureaucracy.

But it wasn’t necessarily a strategy of revitalisation. It was only when Gerstner recognised IBM’s enduring strength – its ability to provide integrated solutions for customers – that IBM was able to reposition itself as a global services business. The key driver of this strategic shift: “listening to and acting on the recommendations of IBM’s 200 top customers”. Gerstner’s great success was to accept IBM’s current predicament whilst establishing a sequence of measures that would shift its business model for a new future.

This leadership outlook of In Flow with the Present is about maturity towards the present to see current challenges as objectively as possible. This cool-headed appraisal is to accept business life “as is” not how it should be: a replay of past strategy from previous success, or a fantasy about what might be possible in the best of all business worlds. This is the opposite of the “ostrich leader” who, reluctant to address pressing problems, denies the reality of the current challenge, or hopes that something will magically turn up to make things better. The in flow leader is alert to the issues as they are, sensitive to the organisational mood, and shrewd in timing the strategic agenda to face and engage with today’s realities. The in flow leader doesn’t promise the impossible. Instead the focus is on: what do we need to do now to make a difference? How will this reposition us for a more resilient future?

Leadership under Siege and Avoiding the Present

For this leader, today is too much. This is the leader who is burdened by the information overload of confusing and complex information and is struggling to juggle the demands of competing stake-holder expectations. Faced with a turbulent world that is moving too much and too fast, the under siege leader adopts any of the following tactics:

- a denial to block out the “brutal facts” of business reality. When Ed Brennan of Sears said “I don’t see any huge problems. I feel very good about how we’re positioned strategically”, presumably he hadn’t reviewed the market data to see the emerging threat of K-Mart and Wal-Mart.

- work harder and smarter to keep up. “Forget strategy, let’s improve execution”. This is the merry-go-round of reorganisation and restructuring that is typically the beginning of the trajectory of decline.

- find a simple strategic narrative that makes sense. This is the one thing mindset, otherwise known as wishful thinking. Rather than grapple with the complexity of the issues, the under siege leader tries to side-step them by focusing on that one aspect of the business they know well and understand (e.g. sales, finance, technology). This tactic may simplify business life; it may also create a lopsided strategy.

Leadership as Impetuosity to Live for the Moment

With a business background in operating motels, Bernie Ebbers’ initial purchase of an obscure telephone carrier and subsequent “17 year acquisition binge” turned WorldCom into the world’s biggest telecoms company, at least for a short time. Admitting “I don’t know technology and engineering. I don’t know accounting” Bernie did think he knew the art of ad-hoc deal-making. When his plan to acquire Sprint Communications for $115 billion was abandoned as the telecoms sector nosedived, WorldCom’s massive debt was exposed along with a series of fraudulent accounting systems. In 2005, Ebbers was convicted of fraud and conspiracy as a result of WorldCom’s false financial reporting.

This leader lives for the moment. This is the enthusiasm to seize the day to get things done quickly. This is leadership which generates “six impossible things before breakfast” in breakneck speed to move the business forward. It’s all go for the impetuous leader.

In the short-run it’s an exhilarating business experience for the leadership team. For businesses that have sunk into complacent lethargy, this leadership stance can inject much needed energy to catalyse an action orientation. In the medium term it becomes exhausting. Caught up in another interesting idea, executives have no time to stop, think and reflect on what is and isn’t working. Initiatives are begun, stopped and restarted; eventually the business begins to second-guess leadership motives: “is this one for real?”

And in the long run it becomes a strategic cul de sac. Without an overarching purpose that coordinates a coherent set of priorities, effort is dissipated in unproductive activity and unprofitable endeavours.

Leadership as Far Sighted about the Future

The final mature attitude identifies that leader who looks to the future. This isn’t the dismissal of the past or the neglect of present priorities; it is the recognition of changing times that demand a shift in thinking to respond to new challenges.

Dan Quayle, in a famous Quaylism, said “the future will be better tomorrow” to much laughter. The far sighted leader sets out a plan for a better tomorrow that establishes credibility and respect, not ridicule. The far sighted leader has the courage and confidence to balance two key dynamics of organisational life – fear (we might fail) and fantasy (things can only get better) – to formulate an inspirational message of future aims with the credibility of a plan to move from today’s realities.

This was the mindset of Andy Grove and Gordon Moore of Intel who astonished the world by abandoning memory chips – the core of their business – to switch to microprocessors. Grove and Moore sat down and asked the tough question: “if we got kicked out and the board brought in a new CEO what do you think that person would do?”

Courage no doubt helped their decision. But key to repositioning Intel for a different future was clear thinking and a willingness to communicate a vision that engaged others’ commitment

Leadership as Fear of the Future

The future is an intimidating and scary place for this leader. Tomorrow is a place with unknown and uncertain challenges, with the threat of current, emerging and unknown competitors, changing customer expectations, and the arrival of new technology. At best this leader displays the kind of caution that is sensitive to risk and avoids the grandiose “bet your company” schemes that might jeopardise the organisation’s future. But more typically, this leadership stance is played out in:

- the stifling of challenging debate about change within the marketplace and the need for a strategic rethink

- the centralisation of decision making to maintain tight control, which managers and the work force find disempowering

- a culture of blame that drives out the risk taking of creativity and innovation

When “fear is in the driving seat” of the leadership team, the organisational dynamics shift to trigger the process of decline. What else but fear could explain the bankruptcy of an organisation like Polaroid, for example? With a proud record in innovation, by the 1970s Polaroid held a monopoly in the instant photography market. And it wasn’t that it didn’t recognise the impact of digital technology; as far back as the early 80s Polaroid were filing patents. Part of the reason for Polaroid’s decline was its assumption that customers would always want a hard copy print. And part was its leadership culture of “chemistry and media first”. They had a considerable amount of fear from the chemical and film people about what their job would be if we got into electronics.” Polaroid’s manoeuvres in the months before its bankruptcy indicate a leadership team without confidence in the business, more concerned to protect its own personal financial position than secure the future for the firms’ investors and workforce.

Leadership as Fantasy about the Future

For this leader, anything is possible. Maybe this leader has done the Tony Robbins fire-walk, because they look to “awaken the giant within” to dream big dreams and think big thoughts. The fantasist can often be the charismatic leader with an electrifying vision of the future and a strategy of radical rethink to prepare for a very different tomorrow. At best the fantasist leader engages with the “hearts and minds” of a demoralised work force to communicate a bright strategic horizon based on a compelling business logic.

More often than not however the fantasist leader – think John DeLorean, Robert Maxwell – is a “Walter Mitty” figure whose dreams are less about strategic realities to formulate a coherent business plan and more a projection of their personal hopes and aspirations. In this fantasy world, the tough reality of financial well-being, competitor threat or customer experience – is blocked. For the fantasist leader, the strategic future is a canvas on to which they paint their personal motives (typically, a variation of greed, ego and status). Unlike the Mafia boss: “It’s not personal, it’s just business”, for the fantasist the opposite applies: “It’s personal.” And it’s rarely good business.

Gerald Levin oversaw the integration of an old time media content company and an exciting internet firm. This was the mega-merger between Time Warner and a vastly overvalued AOL in a $200 billion deal that is now established as “the worst transaction in business history.” A deal “motivated not by logic or strategy but by egos.” A shrewd observer of leadership psychology might have spotted the beginnings of Levin’s fantasy outlook: a preference to discuss books than review the balance sheet; his explanation to oust a long-term colleague as “I’m a strange guy”; spending entire weekends watching movies back to back. “I never feared failure going into the AOL merger.” said Gerry Levin. Maybe a degree of anxiety would have avoided a business fiasco. As one analyst noted: “a fearless CEO should scare every shareholder.” The fantasy continues. Levin now is a director at Moonview Sanctuary, a secluded California facility with “neuro-scientific technology” and “ancient wisdom,” for prices starting at a mere $175,000 a year.

Leadership Wisdom to Connect the Past, Present and Future

During Terry Leahy’s 14 year tenure at Tesco, profits, dividends and earnings per share doubled, delivering a compound annual growth rate of 10%. Tesco is now the world’s third largest retailer. How does Leahy think about time?

On the Past

Tesco’s business heritage lay in a “pile them high, sell them cheap” philosophy, an approach which Leahy’s predecessor Ian McLauren had repositioned and evolved into a winning strategy that was making serious inroads into the market share of the competition. Leahy respected Tesco’s history but he wasn’t in awe of it, a trap into which one of his competitors, Marks & Spencer, almost vanished. Leahy kept asking the question: “what do you think Tesco stands for and what do you wish it stood for?” This is leadership that understands how to build on the past to maintain momentum for growth.

On the Present

Leahy’s business philosophy is simple. “The best place to find the truth is to listen to your customer. They’ll tell you what is good about your business and what’s wrong. And if you keep listening they’ll give you a strategy.” This is leadership not guided by any ideology of what should be; it’s the willingness to face current realities and respond. For Leahy there are no short fixes; it takes many years to build a culture of sustainable success.

On the Future

At the beginning of his time as CEO, Leahy shaped some big goals for Tesco’s future. These weren’t unrealistic promises designed to impress. “All of them were audacious but the company achieved them because they were appropriate and just dramatic enough to motivate everyone. They tapped into what the people in Tesco wanted to achieve.” And Leahy knows the importance of building leadership bench strength for the future. It’s significant that Leahy is only the fifth individual to run Tesco since its founding in the 1920s. In standing down for insider Philip Clarke in a well orchestrated succession plan, Leahy passed on the baton for another chapter in the Tesco book.

Theodore Roosevelt said, “Nine tenths of wisdom consists in being wise in time.” Wise leadership is alert to the productive use of time. It also recognises the power of timing. Wise leadership hinges on the maturity with which we view the past, present and future. Above all, wise leadership realises that the distinction between past, present and future is made in peoples’ minds, and that the three are intimately connected.

References:

1. Kilburg, R. (2006). Executive Wisdom. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

2. “The Seven Pillars of Wisdom” http://www.amazureconsulting.com/files/1/91276339/SevenPillarsofWisdom.pdf

3. Kellerman, B. (2004). Bad Leadership: What It Is, How It Happens, Why It Matters. Cambridge: Harvard Business Review Press.

4. Richard Trowbridge’s summary of the literature is a superb overview of a range of frameworks and definitions. http://www.wisdompage.com/WisdomResearchers/RichardTrowbridge.html

5. Peterson, C. and Seligman, M. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

6. Sternberg, R. and Jordan, H. (2005). A Handbook of Wisdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

7. Anyone interested in accessing these pilot materials should contact Andrew@amazureconsulting.com for further details.

8. “Cultural Competence and the Art of Wisdom”

http://www.amazureconsulting.com/files/1/25898004/CulturalCompetenceAndTheArtofWisdom.pdf

9. Building on the work of Zimbardo (Zimbardo P & Boyd J (1999), “Putting Time in Perspective”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77), we developed a short on line assessment: TimeFrames. Its premise was very simple; how we think about time, our past, present and future, says much about us an individuals and our leadership outlook and priorities. On line resource is also available at www.now-itsabouttime.com.

9. Building on the work of Zimbardo (Zimbardo P & Boyd J (1999), “Putting Time in Perspective”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77), we developed a short on line assessment: TimeFrames. Its premise was very simple; how we think about time, our past, present and future, says much about us an individuals and our leadership outlook and priorities. On line resource is also available at www.now-itsabouttime.com.

About the Author

Andrew Munro (MA, C Psychol) is a Director of AM Azure Consulting, a consultancy specialising in the design of on line applications for talent management, career development and succession. Author of “Practical Succession Management” and “Now It’s About Time” he is a regular speaker and contributor to professional debate.

hi

being involved in research on practical wisdom, I really liked this inspiring article about the proto-integral qualities of wisdom and its links to temporality.

Some questions emerged, for example to learn more about what happens if these interconnected pillars of wisdom get into tensions with each other.

I found the links very helpful to understand the background of this fascinating concept!

looking forward to hear/read more and get into dialogue about these most relevant ideas

kindest regards

wendelin