Patrick Breslin

Difference of Opinion

Coke versus Pepsi. Ford versus Chevy. Conservative versus Liberal. The first set of choices matters little in the grand scheme of things except for those who manufacture, market, sell, and drink carbonated beverages. The second set of choices is more significant since the products are machines containing live human beings moving at high velocity who must be kept safe. The third set reflects the way people want to be led and governed, and the kinds of freedom they desire. For this, we have to consider things other than merely candidates, politics, and policies.

Opinions and decisions about politicians and their actions, along with opinions on any subject that human beings can ponder, arise within the brain. But the role of the brain in politics seldom occurs to most people as they make their political choices. The culture in which people live and their own personal growth within that culture influence how the brain develops and by extension how people think about everything, including the decision of who to vote for. Few people think about the brain’s relationship to that either, but these considerations carry enormous impact in politics. We will look at two experts’ opinions on the brain, personal development, and politics. We’ll also examine the dynamics of communication between people whose partisan views may tend to clash.

Cognitive Science

George Lakoff, Emeritus Professor of Linguistics and Cognitive Science at the University of California at Berkeley, has written several books analyzing brain function with regard to persuasion and political disagreement. He notes that people live their lives according to narratives that define how they see themselves and the world around them. According to Lakoff (2014), the roles and contexts within which we characterize ourselves are frames. Inside of your own frame, you might define yourself as Parent, Spouse, Professional, Sibling, Student, Christian, Jew, Republican, Democrat, Hero, Victim, or any number of labels. The frame “Hero” may be projected onto a soldier, a celebrity, a frontline worker during a pandemic, and so on. Depending on the situation and context, the frame “Victim” might apply equally to these same individuals. Meanings and labels shift when context changes.

We create connections in our brains that construct the components that determine how our framed concepts apply to people or circumstances. We view the world and our place in it according to many conceptual metaphors supported by frames. For example, the notion of a left-to-right scale in American politics is a metaphor (Lakoff, 2009).

When we think about our roles and the roles of others—what it means to be a parent, spouse, hero, etc.—, we forge physical links between the brain cells that sustain the concepts themselves. This is called neural binding (Lakoff, 2009).We create brain structures that support and then become our worldview. Neurons that fire together wire together. The more time and energy we devote to thinking about the connections we understand, the more deeply ingrained those thinking patterns become because we strengthen their links every time we contemplate them.

Suppose I strongly believe that, as a member of my political party, I should support a certain stance on an issue. When I think about the issue, if my thinking is reinforced by input from like-minded members of my party, I embed those opinions into my mind. If I think about them so often that my brain self-wires around a belief supporting a specific side of a controversy, my perspectives will become strongly entrenched within that particular view. In the process I may mentally construct a neural framework so tightly wound that it actually blocks rational rebuttal. If I am then presented with a factual and statistically uncontestable counterargument disproving what I’ve believed, I may be genuinely unable to process it or recognize any validity in it and may immediately toss it aside as nonsense or, to use a more recently popular label, fake news.

If the data don’t support concepts I already trust, I may see them as worthless. Lakoff (2014) states that

Concepts are not things that can be changed just by someone telling us a fact. We may be presented with facts, but for us to make sense of them, they have to fit what is already in the synapses of the brain. Otherwise facts go in and then they go right back out. They are not heard, or they are not accepted as facts, or they mystify us: Why would anyone have said that? Then we label the fact as irrational, crazy, or stupid.

A person’s automatic rejection of a fact that doesn’t line up with an existing worldview would fit Lakoff’s definition of what constitutes a reflexive response—a knee jerk reaction—rather than a reflective response that involves setting aside one’s biases to look deeper into the subject and to consider a different perspective (Lakoff, 2009).

This inability to cognize or consider the value of others’ view crops up in the minds of those who occupy the far left and the far right on the political scale. Most of those afflicted with polarized vision don’t even know that they suffer from it. Dismissing partisanized information that they regard as nonsense feels like a perfectly normal thing to do.

One of the first frame structures we come to understand, according to Lakoff, is family: the combined concepts of parents, siblings, and one’s own role as a child. As we grow up and our view of life expands, we may come to project the family metaphor onto a larger group. We often see our nation as a family, and the government, or our President, as the parent (Lakoff, 2009). In his studies on how this framing of government-as-parent might relate to partisan views, Lakoff determined after extensive research that one’s perspective often reflects an individual’s own family, or their concept of what a family is supposed to look like: The nation is the family, the government is the parent, and the citizens are family members (Lakoff, 2009). In 1970, upon the death of the longtime and well-loved former President of France, Charles de Gaulle, his successor, Georges Pompidou, announced, “Charles de Gaulle is dead. France is a widow” (“France Mourns De Gaulle,” 1970, 1). This is a powerful example of the family metaphor applied to government.

In examining people’s values, Lakoff analyzed political differences with regard to the nation-as-family metaphor, and he discovered that people adhere to one of two basic frames. One is the Strict Father model. This is based on the concept that the father must protect the family—because the mother cannot—, so he works hard to take care of them and imposes strict authority to keep everyone safe. To learn to properly navigate and prosper within our competitive world, potentially wayward children must obey first the father, and then the mother, and adhere to family rules. For the child’s own good, punishment is administered when rules are not followed.

The other model is the Nurturant Parent. In this approach, both parents equally support the children with guidance and empathy, teaching self-responsibility and caring for others. The father and mother are equal partners; one person does not dominate the other. In this model, both parents empower and protect their progeny, and teach them the value of empathy.

According to Lakoff’s detailed research, conservatives project the Strict Father model onto official authority. The government, or the President, becomes the Decider who issues the rules. (In a 2006 interview, George W. Bush famously referred to himself as “the Decider,” and it stuck [Stolberg, 2006].) Citizens comply with authority in order to uphold the security of the nation. Obedience is mandatory, and disobedience is punished. Liberals, on the other hand, project the Nurturant Parent model onto government, envisioning an administration that provides protection, empowerment, and community, and requiring those who disobey to redirect their energy to the support of the community.

Lakoff notes that this is not his opinion of how things ought to be. Years of research and analysis on his part indicate that this is how things are.

The essential difference between the two camps is this: conservatism emphasizes authority and obedience to rules, while liberalism emphasizes empathy and self-responsibility. The concept of empathy is a necessary precursor to the ideal presented in the Declaration of Independence, “All men are created equal,” though even today the desired outcome of that ideal has not been fully achieved (ask any Black American).

Discussing the metaphor of moral order referenced above, Lakoff observes an emergence of power hierarchies in history. These align with the Strict Father model, and lead to attitudes such as “Western Culture above Non-Western culture, America above other nations, Men above Women, Whites above non-Whites, Straights above Gays, Christians above non-Christians,” and so on (Lakoff, 2009). These are dominator hierarchies: one group attempts to rule, control, or suppress another.

Interestingly, Lakoff’s research on these polarized perspectives and hierarchical views of human behavior and government/family metaphors aligns perfectly well with, and is fully substantiated by, the work of another researcher who focuses on something completely different.

Levels of Development

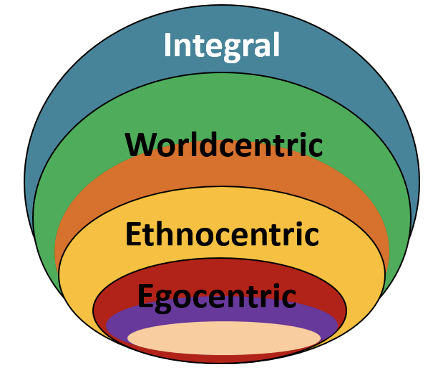

Philosopher Ken Wilber has written more than two dozen books on the study of the phenomenon of consciousness. He has created a format of understanding to provide a context for all human experience. He calls it “AQAL,” an acronymical contraction of “All Quadrants, All Levels, All Lines, All States, All Types” (Wilber, 2001).Each of these perspectival categories is well worth learning about and provides enormous insight into everyday experience. But for this article, we will look at just one of them: the Levels. Wilber has extensively reviewed the studies of developmentalists who research the stages of growth that individuals and societies pass through. This has taken place in the context of psychology, linguistics, ethics, history, anthropology, and religion, all synthesized by Wilber into a comprehensive and overarching framework. Whether you look at individual or societal evolution, the stages remain the same and run mostly parallel from one field of study to the next. Researchers commonly identify seven to nine levels of development, and these can be grouped into three primary categories: Egocentric, Ethnocentric, and Worldcentric.

Egocentric: From early infancy until around the age of seven, most children’s awareness occupies the level known as Egocentric. For youngsters, the world is all about me and my things: “I’m a superhero; I’m a princess; I’m a dinosaur; here are my toys, my bike, my family, my friends,” and so on. The child’s perspective is largely unidirectional, seeing the world primarily from one point of view. Usually, children have not yet learned how to see the world as others see it; they are not “other-oriented.” (Occasionally, some children fail to outgrow this Egocentric perspective. These are often the individuals who later become bullies, and, perhaps much later, criminals.)

Ethnocentric: Beginning roughly around the age of seven, and continuing through the teen years and beyond, most people occupy another stage: Ethnocentric, the belief or conviction that the group to which they belong is the best and most desirable. This is an expansion of compassion, in which the child’s awareness shifts from me to us. “Our family, our friends, our school, our team, our religion, our race, our nation.” Oftentimes this view takes on an exclusivist stance: “Our group is the best in the world, better than all the others.” Wilbur (2019) claims that the majority of adults—70% of the world’s population—function within this perspective from adolescence to the grave.

Worldcentric: Some people at the Ethnocentric stage experience yet another growth of compassion that lets them transcend their own group, and shift to a more inclusive level known as Worldcentric, in which an individual’s perspective evolves from “me” to “us” to “all of us.” A person looking at humanity from the Worldcentric perspective sees commonality between all the peoples of Earth—“We all bleed red”—, and empathically acquires a more pronounced other-oriented perspective.

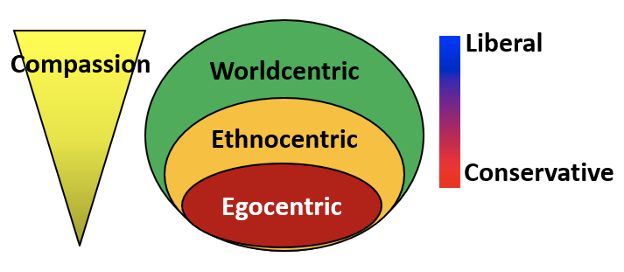

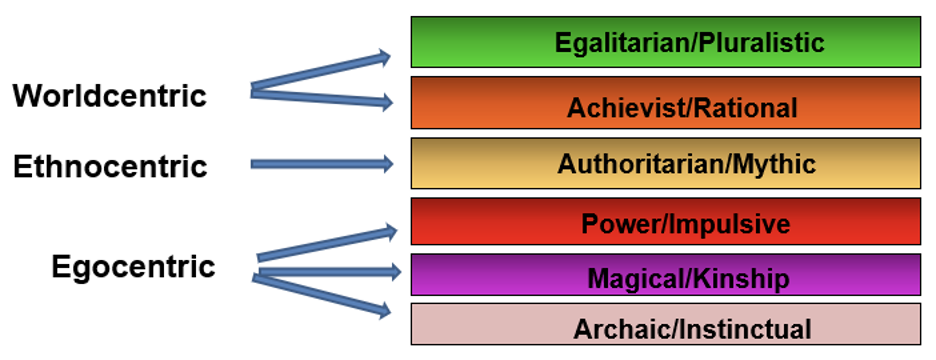

Different terms have been coined by developmentalists to refer to these three levels (Wilber, 2007):

—pre-rational, rational, trans-rational

—pre-conventional, conventional, post-conventional

—selfish, care, universal care

Note that each level in the above image grows into the next one as an elevation and expansion of compassion. We may also state that each level transcends and includes those that precede it. These are regarded as nested hierarchies.

Hierarchies take two forms. One, noted above in Lakoff’s example, is a dominator hierarchy: Men above Women, Whites above non-Whites, Straights above Gays, Christians above non-Christians, and so on. The other is a growth hierarchy, as seen in everyday transformations: caterpillar to butterfly, acorn to oak, fetus to baby to child to teen to adult, and—culturally and psychologically—, Egocentric to Ethnocentric to Worldcentric. One hierarchy oppresses; the other evolves. For now we will examine the top two developmental levels, and return to the lowest one later.

Wilber says that people in the Ethnocentric category see the world in terms of authority and purpose. They believe in an authoritarian entity, such as a king, a God, or a controlling government, which wields power and decrees that rules be followed and laws be obeyed for the good of society. Historically, this perspective dominated human culture from approximately 5,000 years ago (Wilber, 2008) until the dawn of the European Enlightenment in the 1700s (Wilber, 2000).

Lakoff and Wilber both note that the Enlightenment gave birth to Liberalism (Lakoff, 2009; Wilber, 2000). This came about as a reaction to dominator hierarchies. The Enlightenment rebellion was supposed to free us from the dictates of religions and kings, and also to recognize the importance of reason as the guiding force of human affairs. Reason was destined to make us all equal and free, allowing for the creation of government based on “the rational interests of all citizens (Lakoff, 2009);” it would allow government to follow the luminous guidance of science and to structure itself in democracy. Lakoff (2009) states that “Our Constitution is in large part based on the intellectual tools and ideas inherited by its framers from Enlightenment thinkers”. We’ll revisit this shortly.

The characteristics of Wilber’s Ethnocentric level match up with Lakoff’s Strict Father/Conservative Government model. Pre-Enlightenment government functioned under the control of a king, who in turn was nominally ruled by God; this was a nearly universal metaphor for a monarchical hierarchy. Most people living in this environment would not have entertained the thought of any alternative parental model to the Strict Father, or the system of government that it reflects. They were accustomed to the dominator hierarchy.

The Strict Father/Conservative Government model fits into the Ethnocentric framework like a door into a wall. The latter fully supports the dominator hierarchy that the former promotes.

Post-Enlightenment Compassion

Liberalism born of the Enlightenment gave people the initiative to think in terms of reason, to employ logic and science, and to seek answers rationally rather than emotionally or under kingly command. It also gave them societal permission and impetus to fight injustice because they felt compassion for those oppressed, for those held down by dominator hierarchies. If this expansion of compassion were to be mapped alongside Wilber’s levels, and if we were to add the customary left-to-right political metaphor rotated 90 degrees clockwise to reflect the levels of compassion within it, we would get this:

Please note that the placement of “Conservative” at the lower end of the spectrum on the right is not meant to be an insult. It is a measurement of available compassion, historically and psychologically proven to be in short supply at that stage. Like vocabulary, it increases over time. We don’t start out in life with a surplus of words or compassion. We all begin at the lowest end, the Egocentric level, where “Everything is all about me.” Attaining the next level up, identifying with “people who are like me,” requires that you first acquire compassion for those people, which comes naturally to most of us. Within that level, people may try to ensure an ongoing supply of compassion for themselves by distrusting outsiders who might take it away—a less than mature view of emotion, but basic survival supersedes the understanding of feelings.

To take the next step up, to cultivate global compassion for those outside of one’s group, requires immersion in or exposure to an environment that provides multiple perspectives on life, an environment that teaches and promotes the notion that differentness is acceptable and even desirable. You become Worldcentric only when those around you are already there; otherwise, you remain embedded in the Ethnocentric worldview of your contemporaries. (Rare exceptions occur; Jesus comes to mind.)

These are all stages of growth, and we attain them sequentially. In the process, we see that those who occupy the lower stages that we’ve outgrown may need nurturing and support. You wouldn’t belittle a small child for being a small child, and you wouldn’t berate a 20 year old for not having the same life experiences as a 40 year old. If the small child is misbehaving, an adult would hopefully step up and humanely correct the problem. However, if an adult maligns or mistreats specific groups of people solely because they’re outsiders, and does so within a community that doesn’t think mistreatment of outsiders is a proper approach, conflicts will arise. This is where Ethnocentric and Worldcentric clash.

If you haven’t already suspected it, the levels don’t understand each other, and therefore don’t get along well. Egocentric individuals regard Ethnocentrics as fools for not solely looking out for number one and for focusing on the wellbeing of others in their own group instead. Moreover, they see Worldcentrics as tree-hugging hippies. Ethnocentric individuals disdain Egocentrics as selfish brutes, and Worldcentrics as, again, tree-hugging hippies. Egocentrics are seen as selfish brutes by Worldcentrics, who also regard Ethnocentrics as discriminatory and oppressive.

But there is a place where the latter two groups overlap, in what amounts to Worldcentric Part One. Before the current egalitarian version of Worldcentrism—the tree-hugging hippie level—made its debut, a preliminary component took the stage for a couple of centuries. (A developmental timeline on this will be provided shortly.)

The description of levels noted above was interpolated from the Psychological Map of Dr. Clare Graves, adapted by Don Beck and Christopher Cowan, creators of the Spiral Dynamics(R) program. They used colors as a type of visual shorthand. Wilber followed suit, assigning red to the Egocentric level, amberto the Ethnocentric level, and green to the broader category of the next level up. However, this latter stage, prior to blossoming into its current form, was presaged by a slightly different incarnation that could be called Achievist, with orange as its assigned hue. For the moment, we’ll refer to the phase that grew out of that level as Egalitarian or green. To clarify, Achievist and Egalitarian are the two levels within the Worldcentric domain, which is one step up from Ethnocentric.

With the rise of the European Enlightenment came the idea that people could do things differently than before. They could cast off the yoke of oppression and explore new possibilities in work and personal attainments. This was the Achievist level. Empowering and empowered by the oncoming industrial revolution, with the scientific revolution thrown in for good measure, many members of society flourished in a newly discovered mechanistic universe that promised material gain. Laws of science were applied to the economy, politics, and other human activities (Wilber, 2000). Those who worked smarter in this domain succeeded. The falling away of Ethnocentric oppressions freed many to reach for new horizons.

The authoritarian Ethnocentric level had created mighty civilizations during the preceding centuries, and its members are defined by more than their occasional repression or rejection of outsiders. They were also highly industrious. For this reason, Ethnocentrics had good reason to celebrate this new Enlightenment-based impetus to thrive. The idea that hard work will produce success for oneself and hence for the family that one supports is a perfect moral frame for the Achievist level of consciousness. Lakoff (2009) states that “the strict father model links morality with prosperity. The same discipline you need to be moral is what allows you to prosper. The link is individual responsibility and the pursuit of self-interest.” Here within the Achievist stage, the controlling self-discipline of the Strict Father/Ethnocentric level and the freedom-from-oppression mindset of the Nurturing Parent/Egalitarian level found common ground for a long time.

But not forever. As the decades passed and empathic people saw that oppression still existed, most notably against women and people of African descent (though many other groups suffered as well), changes seeped into Western society. Beginning in the mid-1800s, abolitionists and women suffragists made their voices heard in a gradually ascending howl. Newly emerging Egalitarianism was gearing up for a fight.

Interiors

Lakoff (2009) discusses the Enlightenment view of reason: “conscious, literal, logical, universal, unemotional, disembodied, and [it] serves self-interest.” Many of these characteristics have been internalized by liberals as indispensable guidelines for making decisions and for justifying behaviors. But cognitive science shows that the brain doesn’t automatically follow such guidelines. Lakoff’s (2009) research indicates that 98% of thought is unconscious, much of it embedded as metaphor, and based upon frames, all tied into feelings. To put it another way, ideas converted to feelings cease to be abstract thought; they become visceral, and hence cannot be consciously manipulated.The type of thinking by which people decide what’s important doesn’t happen on the surface of awareness, though we like to pretend otherwise. Because of their commitment to reason, many liberals, and especially liberal politicians, try to employ logic structures as tools of influence, but because the brain isn’t particularly reasonable, many don’t succeed at it. A liberal himself, Lakoff is frustrated with the lack of understanding on the part of most liberals as to how this works, or fails to work. He is disappointed that his cohorts are unskilled at the art of persuasion, especially when contrasted with the effective way political conservatives manage to pull it off.

He notes that during the second half of the 20th Century, conservatives began joining forces for their common benefit. Setting aside their differences, they became well-organized, and over the years they created conservative think tanks, funded university professorships, established foundations, trained conservative spokespeople, and generated entire bodies of literature explaining and justifying conservative values. They stumbled upon and then ultimately mastered the science of structuring vocabulary around the values that hit home with large numbers of people (Lakoff, 2014). Many Americans on the receiving end of conservative messages have embraced those values, which often refer to patriotism, authority, freedom, and family, ideas all laden with emotion—embedded within frames—, which are inescapably interior. Right-wing American citizens, in the process of absorbing and aligning themselves with this, have developed a unified identity whose burgeoning solidarity has caused the national metric of partisanship to shift toward the right for the last few decades. Lakoff feels that what used to be moderate is now seen as leftist, and what used to be somewhat conservative is now centrist (Williams, 2014).

In contrast, most liberal politicians did not link their ideas to emotions, or even think about doing so. Even though their primary motivation has always been compassion—an interior emotional trait—, they’ve tended to be well-educated logical thinkers who prefer to employ tools of reason—exterior attributes—to get their points across. But they didn’t relate those points to people’s feelings or to the metaphorical images that make up the foundations of people’s worldviews. They assumed that stating ideas logically was enough. It wasn’t. Liberals have been largely ignorant of ways to connect their platforms to value-framed emotions, which lie at the core of decision making. Focusing on exterior concepts and ignoring interior feelings, they didn’t know how to bind lofty thoughts to people’s hearts.

Authoritarianism

During the last few decades while conservative politicians cunningly swayed people’s perspectives with framed emotions dressed as political narrative, and liberal politicians were wondering why more people weren’t listening to them, our country was evolving its way through a cultural revolution. Years of simmering discontent beginning in the mid-1800s led up to the culture wars of the 1960s, where protests were fueled with revolutionary zeal. Women’s liberation, black power, gay rights, and other initiatives came to a boil, with liberal green Egalitarianism turning up the heat. Laws were passed, obstructions removed, and justice established in places that had not known it before. Women’s rights were expanded to include greater access to equal pay and reproductive options, African-Americans achieved desegregation in businesses, gay Americans advanced anti-discrimination legislation, and other marginalized citizens experienced new degrees of inclusiveness.

Recall that these changes reflect and are driven by the growth of compassion, which focuses initially on oneself, then one’s group, then the world. In order to manifest this in society, compassion had to be converted into policy and law. But in the moment compassion is legislated into legal directives and sent forth to transform the world, it becomes an exteriorized feature that is unmindful of the significant interior factors that generated it in the first place.

Liberal inclusiveness mandated that no one should be left out, that everyone should be equally valued and cherished. This created a problem. Liberalism’s belief that no group’s values should be disrespected or devalued, and that all should be on equal footing, reveals the failure of almost all liberals to recognize that the compassion that empowered this enterprise did not exist in the lower levels to which equal value was now granted and to whose members the idea of reciprocating in kind was entirely alien. Wilber (2017) defines this as a performative contradiction, a structurally flawed initiative that, in the process of carrying out its mission, shoots itself in the foot. He states that

From the beginning, liberalism therefore misunderstood the genesis of its own stance. It failed to grasp the fact that liberal values arise only through a series of interior, nested, hierarchical stages of growth—and liberal values are fairly late-emerging values at that (…red to amber to orange, at which point liberal values begin to emerge…). Therefore liberalism—because it was in fact a postconventional, worldcentric, universal wave of fairness, justice, and tolerance—immediately extended to all the other stages the status of equal value, even when those lower stages, such as red and amber, had no intention of returning the favor—and, in fact, were they in power, would crush liberalism as soon as they possibly could. And every time those lower stages do come into power today, the first thing they attack and attempt to eradicate is liberal freedoms (Wilber, 2020b)

Borrowing from the vocabulary of Beck and Cowan, Wilber labels each of the growth hierarchy levels as memes. The green Egalitarian meme has its own fringe element. This subset of Egalitarianism that demands that the noninclusive world immediately and fully embrace universal inclusivity is called the mean green meme (Wilber, n.d.).Lakoff, from his unique vantage point within the field of linguistics and cognitive science, recognizes the exact same phenomenon and identifies it with the more verbose yet equally poetic moniker of authoritarian antiauthoritarianism (2009).Within politics, conservatives might label such people the intolerant left, though the more extreme sub-subset of the latter group would be tagged as the radical left. (Some far-right conservatives are inclined to stamp this brand on everyone left of center.)

Egalitarian liberalism, possessing greater compassion, should hypothetically be able to promote universal fairness and guide society to more advanced stages of development. But the attempt to force inclusiveness upon individuals who lack the heart for it, who don’t feel or grasp the compassion behind it, creates backlash. Trying to compel people to climb to higher ground when they can’t understand that their lives would be better up there is like herding cats. They don’t comply because they don’t see a reason.

While all this is going on, amber Ethnocentrics fight other amber Ethnocentrics—ethnic groups, races, nations, factions, religions, denominations—, and then they clash with green Egalitarians who want to fix them. Amber yells, “We’re right, we’re superior because we’re right, and you are guilty of not being us!“, while green demands that everyone love everyone else, and then becomes exasperated when no one listens. For this reason, Wilber (2017) feels that green is broken. But there are other levels yet to discuss, and other contexts to consider.

The developmental level you occupy is one that you’ve grown into from the level below it. Compassion tends to increase in the heart of the average person, and so we move up. We don’t regress downward except in crisis. Many Worldcentric Americans took a step back to Ethnocentric on September 11, 2001, when the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were attacked by Islamist terrorists. For months thereafter, rallying cries of “USA! USA!” were ubiquitous. Flag vendors made a fortune, patriotism swept the land, and anti-Muslim bias was omnipresent, because almost no one at the time understood the difference between Muslims who, like Christians, strive to be good people, and Islamists who deceptively don the cloak of religion to justify war. (Amber within amber: you can’t get more Ethnocentric than that.)

Within the two domains of amber Ethnocentrism and green Egalitarianism—that is, among conservatives and liberals—are many wonderful people (a majority, in fact) who love their country and society. Two superb examples in American government in recent memory have been, respectively, George W. Bush and Barack Obama. Moral people such as they constitute the mainstream population on both sides of the aisle, despite their myriad detractors. But each category, each party, is afflicted with its own uncivil fringes and offshoots whose members and whose media describe the other group in hateful terms that, if believed, become part of the neural binding and cognitive dissonance of those who absorb the distortion as truth.

We often hear individuals in the media, and in our own communities, using generalized, derogatory vocabulary against those who they consider to be their political opponents, slamming the entire group as essentially evil or unpatriotic—“The Left wants to destroy this country!” “Right-wingers want to stamp out human rights!” If you hear someone claim that most if not all of American conservatives (121 million) or liberals (79 million) (Chapman, 2020) are misguided, mistaken, unbalanced, unhinged, and flawed human beings, then pay close attention to how you react. If you question what you hear, and if you recognize that the rhetoric doesn’t provide an accurate picture of the people being described (especially if you know some of them personally), then your objectivity is intact and you can trust your reasoning. However, if the sweeping deprecations aimed at the other group sound plausible to you, be aware that your sensibility has been compromised, and fairness and objectivity are not presently part of your mental wiring. In other words, if you feel only antagonism, antipathy, general dislike, or even hate for millions of “them,” the problem is you—meaning that you don’t know enough about “them” or you.

Sadly, many citizens, and the occasional rare politician, dwell on a lower level, functioning within a red Egocentric domain, and hauling down multiple amber Ethnocentrics with them, while completely—and intentionally—alienating green Egalitarians. (In early 2021, the Oval Office bade farewell to such a red Egocentric individual.) When they feel they’re under attack, they exhibit two behaviors: (a) shifting blame for negative repercussions of their actions onto others, and (b) hurling multiple insults at targeted individuals on an endless basis (Lakoff, 2016). This latter behavior, name-calling, is their super power. If you see someone demonstrate an ongoing pattern of badmouthing multiple people, you have identified a denizen of the lowest developmental level. Listen to them at your peril; if you buy what they’re selling, you may be seduced into a feeling of righteousness which is just hate in drag.

Tiers

As previously noted, one characteristic shared by all the levels is that they don’t understand each other; occupants of each level don’t grasp the worldviews of outsiders. Subjectively, everyone feels justified in their beliefs, and often resent all the other people who “just don’t get it.” This applies not only to the summarized “big three” categories of Egocentric, Ethnocentric, and Worldcentric, but to the sublevels that comprise them. They are depicted here as strata:

To summarize their perspectives (Wilber, 2000):

—The bottom beginner level, Archaic/Instinctual, applies to newborn infants, Alzheimer’s patients, and mentally ill street people, who focus on food, water, comfort, and basic survival. This also constituted the perspectival level of consciousness in human survival bands around 100,000 years ago.

—The Magical/Kinship level pertains to toddlers up to the age of 3. It’s seen as belief in fairies, Santa Claus, good luck charms, and witchcraft. It had its origins in human pre-cultures 50,000 years ago.

—The Power/Impulsive level appears in children experiencing tantrums, epic heroes, gang leaders, Darth Vader, Marvel/DC super-villains, and out-of-control rock stars. It was seen in warlord empires 10,000 years ago.

—The Authoritarian/Mythic level sees life that has meaning and purpose directed by an Order that strictly defines all rules and punishes rule-breakers. It includes rigid social hierarchies and characterizes not only fundamentalist religion but also atheist totalitarianism. It began in early nation-states 5,000 years ago.

—The Achievist/Rational level views life in a scientifically defined universe where laws of logic apply to everything. It values material progress, earnings, Wall Street, and corporations. It started with the Enlightenment 300 years ago.

—The Egalitarian/Pluralistic level focuses on equality, caring, relationships, and the Earth. It favors antihierarchical and multicultural systems. It began around 150 years ago.

Individuals and cultures usually evolve through stages without realizing that that’s what they’re doing. These are the people who don’t recognize that they occupy developmental stages rather than merely different cultures, ethnic groups, races, political parties, or religious persuasions. This characterizes all the groups we’ve looked at thus far, and they are collectively referred to as the First Tier. But a small percentage of those who have outgrown these levels by virtue of their own studies, research, or personal experience move up to what is called Second Tier. People who make it this far realize that they have risen through hierarchical phases. This perspective can be labeled Integral. This, like the prior levels, transcends and includes those that precede it within a nested hierarchy of growth. Its placement within a concentric depiction looks like this.

In general discussion, the Egocentric level (Power/Impulsive) at the bottom end of the compassion spectrum is referred to in terms of the color red, even though two more rudimentary levels with their own corresponding hues are subsumed within it. The Integral level is represented by the color teal, though it, too, contains subcategories (Wilber, 2020a)

A teal Integral person will appear to be a green Egalitarian. The rest of the world will see them as liberal. But this person won’t try to impose psycho-emotional evolution on those who aren’t ready for it, or shove inclusiveness down anyone’s throat. Because they recognize the growth stages in other people, they will attempt to communicate within the level of the listener, hopefully guiding others in the direction of increased compassion. Lakoff (2014) promotes this when his students ask him

…[W]hat to say at Thanksgiving dinner? …Ask your aunt or grandfather what they are most proud of that helped other people. Those of my students who have done this report that, to their surprise, their grandfather or other relative did a number of good things to help others and show some important social concerns. My next bit of advice: Keep talking about those things. (Italics mine.)

If you prompt people to think about their own acts of empathy, you may contribute to their orientation toward compassion and away from bias against outsiders, and thus towards the Egalitarian stage, and potentially closer to Integral. Perhaps 5% of the world’s population occupies an Integral stage. Wilber notes that in the past, a civilization would evolve to the next level of growth when its percentile demographic in that stage reached 10%. This seems to be the tipping point. Integral is not there yet, but it’s coming.

Deliberative Dialogue

Arguments often polarize along liberal and conservative lines. These may cover a wide range of topics: gun laws, the economy, health care, death penalty, gay marriage, immigration, religion, taxes, welfare, budget deficit, global warming, and more (“Are You Conservative or Liberal,” 2013; “Views of Parties’ Positions,” 2016). Yet very few people adhere to only liberal or conservative perspectives on every issue; more often than not, an individual’s attitudes may vary from one topic to the next. For example, some liberals are anti-abortion, and some conservatives are pro-choice, bucking the trend of their cohorts (Diamant, 2020). Lakoff (2006) uses the term “biconceptuals” to define those whose liberal or conservative affiliation—Nurturant Parent vs. Strict Father—may fluctuate from one issue to the next.

They use both models actively—but in different parts of their lives. They may be strict at home but nurturant on the job, or the reverse. There are a lot of blue collar workers who are strict fathers at home but nurturant in their union politics, and professors who are nurturant at home and in their politics but strict in the classroom. One may be an economic progressive and a social conservative—or an economic conservative and a social progressive. Or one may be a progressive on domestic policy and a neo-conservative on foreign policy (Lakoff, 2006).

How is this possible? Lakoff (2014) states that neural binding occurs differently around different issues. For each issue, mutual inhibition may take place: one system in the brain switches off and another becomes active. The two cannot dominate simultaneously; you can’t be “for” and “against” the same thing at the same time. Even though many people identify as moderate, Lakoff (2014) feels that there is “…no morally based political ideology common to all moderates.” In our increasingly extremist culture, some self-labeled moderates avoid aligning themselves with either wing, and by calling themselves moderate they merely mean non-extreme or non-radical.

For people to understand one another, especially with regard to controversial topics, they must listen to each other’s opinion. Thinking about opposing views reflectively, with measured consideration as noted above, rather than reflexively, as an automatic rejection of an idea that doesn’t feel right (or an instant acceptance of one that does), requires mindful consideration. It can be cultivated in a process called deliberative dialogue. This communication method differs from debate. According to John Theis (2017) with the Center for Civic Engagement at Lone Star College, “The purpose of deliberation… is to frame the type of decision that might ultimately have to be made. Debate can settle where to build a bridge. Deliberation determines whether or not a bridge should be built and, if so, for what purpose.” The process is collaborative rather than confrontational. It assumes concern for others, seeks meaning in agreement, and looks for common ground. And it applies extremely well to individuals with opposing views on controversial topics.

The underlying beliefs of personal narratives come to the surface in this process. This allows individuals to see what others are feeling, what they can empathize with, and what they have in common (London, 2005). The process also reveals hidden assumptions—the conceptual underpinnings of Lakoff’s frames—that can be scrutinized and discussed. Participants can then see the world through others’ eyes. This leads to the growth of compassion.

Reflective Compassion

Wilber’s (2017) research indicates that in the current first half of the twenty-first century, 70% of the world’s population functions at the Ethnocentric level (or below); in the U.S., it’s around 60%. Amber Ethnocentric conservatives tend to prefer their politics served up with values framed as connections to the heart: home, family, faith, authority, patriotism, and so on. Liberals have much the same value preferences—who doesn’t love home and family?—, though their communication style still tends to hover up in the lofty realms of reason and logic, and most of them haven’t gotten the hang of bringing those down to earth. Consequently, messages generated by liberal politicians still often fail to resonate with the current conservative amber majority.

We all know people who prefer their political perspectives neatly summarized in a clever slogan or at most a brief paragraph that packs a punch. Many would not read an article as long as this one, especially one that ventures into apparently nonpolitical terrain, unless it praised their preferred candidate or party, or badmouthed the opposing team. These basically moral people are fenced in by limited awareness that doesn’t allow for reflective deliberation or exploration.

But for the insightful and reflective person, the consideration of cultural and historical information provides politics with context. It allows one to understand the systemic origins that evolved into the culture that surrounds us today and that contributes to our partisan perspectives. Politics is not just a statement about which good or bad action is committed by this individual or that political party. Politics is an expression of evolving cultural dynamics that span thousands of years. It’s part of a centuries-old cumulative manifestation of history, language, literature, religion, philosophy, and science, all of which accompanied humanity’s expansion across the globe. Civilizations have risen and declined, nations have proliferated, reshuffled, and been absorbed into other nations, empires have appeared and vanished, and rulers and royalty have conquered, succumbed, and transformed into multiple machinations of government. All the while, neurons in human brains created pictures of what they wanted the world to look like and who they wanted to be in charge of it. Built upon the bones of millions upon millions of past lives, human political history culminates in the consciousness of the present-day voter who casts a ballot that asks, “What’s in it for me?” Everyone seeks support and acceptance while avoiding rejection and hate.

Love is learned at red Egocentric. Hate is learned there also. Both may expand within amber Ethnocentric; love can get better, hate can get worse. But if you weren’t taught to hate, you won’t consciously adopt it as a default response for interacting with strangers, though you might be tricked into doing so if you become convinced that your survival depends on it. Societies that promote hate have been known to elevate it to the status of a virtue. When this is experienced in the context of a group consciousness or an environment that encourages it, hate can feel like focused love: “We raise ourselves up by putting outsiders down.” How should we deal with a person whose consciousness dwells deeply within the Ethnocentric or even the Egocentric stages, considering the hate and non-inclusiveness that that may entail? Wilber (2017) says

For such an individual, our appropriate response is to feel not a gloating moral superiority, but a truly deep compassion for someone living within the unbelievably constricting, suffocating, and suffering-inducing stages that these are—and from an integral view, compassion is the only judgmental attitude we’re allowed—the only one.

Compassion toward people who may regard you as wrong, crazed, or possibly evil can be difficult to cultivate, but it’s worth a judicious try. The level of compassion needed to graduate from amber through orange to green is indispensable to promote peaceful interaction, or at least to avoid conflict. At the green Egalitarian level, maturity is as crucial as empathy, especially if one is to continue on to Integral.

Lakoff (2014) mentions hypocognition¸ a lack of ideas or terms briefly summarizable in a word or two which convey an important concept that can be readily addressed. Most liberals don’t have a word for what they should do next in the world, or where they might go beyond the inclusive space they try to create. The question doesn’t cross their minds. Moreover, in our current political climate the definition of one’s partisanship doesn’t allow for discussion of Integral level awareness; few people have heard of it. If I were to tell people that I am integral, it may sound as if I’m anti-segregation (correct) or that I see myself as a crucial part of some organization (questionable). But if I state that I’m teal, they might recommend matching shoes and accessories. These two terms probably won’t be trending in the media anytime soon. Therefore, when asked if I’m a liberal, I reply yes, in the same spirit that I would answer yes if asked whether I wear a wristwatch. But “liberal” is not a club I belong to, nor a characteristic on which I base my identity. Nevertheless, in the context of political pigeonholes, it’s less incomplete than others.

To work around the lack of a recognizable second-tier political designation within the severely limiting vocabulary of partisan language that screens out far more significant components of life than it reveals, I default to calling myself “a conservative liberal, about one-third of the way from mid-point to the Left.” I then try to address people where they are, at their own level of development, in their own terms, in hope of enhancing awareness of compassion in their lives. My political perspective is also my view of being human: I’m a believer in and promoter of reflective compassion. I endeavor to demonstrate empathy toward any human being who bears me no ill will, and even some who do; and to the extent that my wellbeing and solvency allow, if it’s within my power to do so, I will help anyone who asks. First, I listen.

References

Chapman, M. W. (2020). Gallup: Americans’ ideology, 37% conservative, 24% liberal, 35% moderate. CNS News, The Media Research Center. https://www.cnsnews.com/article/national/michael-w-chapman/gallup-americans-ideology-37-conservative-24-liberal-35-moderate

Diamant, J. (2020). Three-in-ten or more Democrats and Republicans don’t agree with their party on abortion. FACTTank News in the Numbers, Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/18/three-in-ten-or-more-democrats-and-republicans-dont-agree-with-their-party-on-abortion/

Inter Press Service News Agency. (2013) Are you conservative or liberal? LPS. http://wp.lps.org/tnettle/files/2013/12/Liberal-vs-Conservative.pdf

Lakoff, G. (2014). The all new don’t think of an elephant. White River Junction, VT, Chelsea Green Publishing.

Lakoff, G. (2009). The political mind. New York, Penguin Books.

Lakoff, G. (2016). Understanding Trump. University of Chicago. https://press.uchicago.edu/books/excerpt/2016/lakoff_trump.html.

Lakoff, G. (2006). Whose freedom? The battle over America’s most important idea. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

London, S. (2005). Thinking together: The power of deliberative dialogue. Adapted from Kingston, R. J. (Ed.) The power of deliberative dialogue. Public Thought and Foreign Policy. http://scott.london/reports/dialogue.html.

Pew Research Center, U.S. Politics. (2016). Views of parties’ positions on issues, ideologies. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2016/06/22/5-views-of-parties-positions-on-issues-ideologies/

Stolberg, S. G. (2006). The decider. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/24/weekinreview/the-decider.html

Theis, J. (2017). Moderating for deliberative dialogue. Gainesville, FL: Workshop, Santa Fe College.

France mourns De Gaulle; world leaders to attend a service at Notre Dame. (1970, November 1). The New York Times. 1.

Wilber, K. (2001). A theory of everything. Boston, Shambhala Publications.

Wilber, K. (2020a). AQAL integral map. https://integrallife.com/what-is-integral-approach.

Wilber, K. (2020b). Integral politics: a summary of its essential ingredients. 16.(https://integral-life-home.s3.amazonaws.com/Wilber-IntegralPolitics-ItsEssentialIngredients.pdf)

Wilber, K. (2008). Integral third-way politics.” 15:51. www.kenwilber.com/blog/show/446.

Wilber, K. (2007). The integral vision. Boston, Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Wilber, K. (2019). The leading edge of the unknown in the human being. video, 1:31:56. https://www.scienceandnonduality.com/article/the-leading-edge-of-the-unknown-in-the-human-being-ken-wilber.

Wilber, K. (2017). Trump and a post-truth world. Boulder, Shambhala Publications, Inc. 2017.

Williams, Z (2014). George Lakoff: “Conservatives don’t follow the polls, they want to change them … Liberals do everything wrong”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/feb/01/george-lakoff-interview.

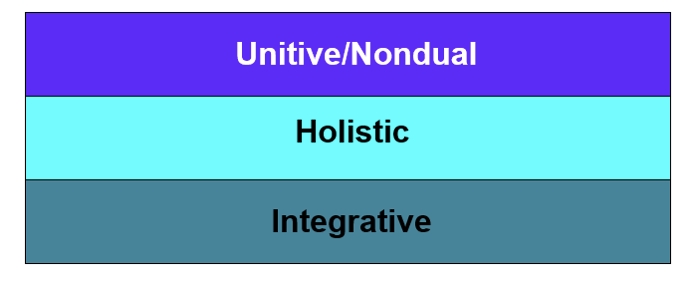

Appendix The sublevels of Wilber’s (2020a) Second Tier or teal stage merit a brief review.

From the bottom up:

—The Integrative level possesses awareness of nested hierarchies and the necessity of stages of development. The individual who arrives at this level respects people where they are, recognizing that they’re on a journey of growth and learning. This perspective began around the mid 1900s.

—The Holistic level is a shared “We” perspective of a universal integrative system and interactive dynamics. People at this level possess awareness of nested hierarchies and the necessity of stages of development. This began around the early 1980s.

—The Intuitive/Nondual level sees everybody as an extension of oneself. The ego expands to include the world. Though sporadically appearing in unique individuals during the last few dozen centuries, often in the context of contemplative religion or spirituality, this stage has begin very gradually manifesting itself in the general population since the 1990s.

The top two higher stages embody an outgrowth of Ken Wilber’s personal search for spiritual enlightenment which drove him to study these matters ever since he was a college student. He immersed himself in meditation and spiritual studies which contributed to his creation of the AQAL curriculum. (My own modest journey within the same fields led me to his works.)

About the Author

Pat Breslin teaches Public Speaking at Santa Fe College in Gainesville, Florida. His main field of academic interest involves the intersection of persuasive communication and the developmental growth of consciousness.