8/31 – Reinventing Organizations: “A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness”

Ron Cacioppe and Michael Fox

Ron Cacioppe and Michael Fox

Reinventing Organizations by Frederic Laloux

Reinventing Organizations by Frederic Laloux

Ron Cacioppe

is a ground breaking book that describes how the functioning and structure of organisations evolves over time to match the level of development of human consciousness. Organisations go through stages that are radically different, becoming more productive, collaborative and reach a higher level of functioning. Each stage “transcends and includes” the ones that came before, therefore a later stage does not lose the behaviours that came from earlier stages but earlier stages obviously cannot access the insights of later stages. And we are moving into a stage which will have radically different characteristics than many organisations currently demonstrate.

Laloux states that a whole new shift in consciousness is currently underway that will result in a radically more purposeful and spiritual way to run our businesses, non-profits, schools and hospitals.

Michael Fox

This book is an important management book to read now since it describes the organisations of the future. It articulates the framework needed for better organisations that can grow and adapt to work in complex environments. “Reinventing Organizations” describes in practical detail how organisations large and small can operate in a new paradigm. Leaders, founders, coaches, and consultants will find this book a positive handbook full of insights, examples and inspiring stories.

History and Development of Organisations and Consciousness

Laloux traces this development from 100,000 BC to the present, observing a gradual but accelerating evolution from simple ‘family kinships’ to ever more collaborative and powerful forms of organisations. He shows how at this moment we are at another historical junction. The current management methods feel outdated and exhausted. And a new organisational model is emerging, a radical new way to structure and run organisations. He calls this the Evolutionary-Teal model (ET model). The ET model’s development can be seen as a response to an expanding global consciousness – a growing awareness that ‘the ultimate goal in life is not to be successful or loved, but to become the truest expression of ourselves . . . and to be of service to humanity and our world . . . [to see life] as a journey of personal and collective unfolding towards our true nature’.

Part 1 puts forward a sweeping evolutionary summary presenting a 100,000-year “history” of organisational development and the types of consciousness that gave rise to different organisational structures, leading to present times. It explains how every time humanity has shifted to a new stage of consciousness, it has also invented a radically more productive organisational model and suggest we are facing another critical juncture today.

Part 2 serves as a practical handbook. Using stories from real-life case examples (businesses and non-profits, schools and hospitals), this part describes in detail how this new, spiritual way to run an organisation works. The second part of the book describes the structures, core practices and culture of Teal Organisations through a series of case studies. The twelve cases in the book consist of profit and non-profit organisations of various sizes from the United States and Europe.

Part 3 examines the conditions for these new organisations to thrive and what is needed to start an organisation on this new model. It also describes what is needed to transform existing organisations.

The Problems with Current Organisational Models

The way we manage organisations seems increasingly out of date and unable to cope with the complexity and challenge of modern times. The idea that most organisations should operate for shareholder profit or by political or not-for-profit leaders who have short-term self-interest, indicate that our current organisational models aren’t sufficient. Deep inside we sense that more is possible and we long for workplaces which nurture human development, authenticity, community, passion, and purpose.

Laloux challenges the status quo and asks, “Can we create organisations free of the pathologies that show up all too often in the workplace? Free of politics, bureaucracy, and infighting; free of stress and burnout; free of resignation, resentment and apathy; free of posturing at the top and the drudgery at the bottom? Is it possible to reinvent organisations, to devise a new model that makes work productive, fulfilling and meaningful? Can we create soulful workplaces – schools, hospitals, businesses and non-profits – where our talent can bloom and our callings can be honoured?”

We need something more: enlightened leaders and enlightened organisational structures and practices. This book demonstrates that this is possible and already exists in a few organisations.

History of Stages Human Evolution and Organisational Structures

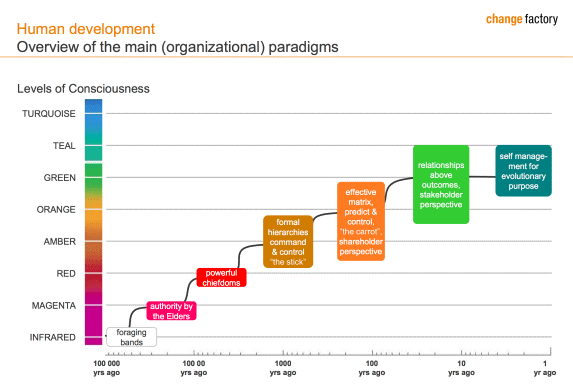

Laloux makes the case that human consciousness evolved in stages, which he classified by colour, each colour representing a stage of development that gave rise to an organisational culture “fit” for the epoch it arose in. Each stage of development or colour, correlates with a particular time in human history and each “stage of development” represents a certain “cognitive, psychological and moral” orientation.

Laloux uses the Integral Theory and its colour scheme to describe these historical developments of human organisations. The diagram below outlines the stages and the key characteristics that humans have undergone in tribes and organisations in the last 100,000 years.

The spectrum looks like this:

Humans first lived in family kinships. Next, tribes were formed, and life was controlled by magical rituals. Then the first chiefdoms were formed, ruled by power and suppression. The main stages this book concerns itself with are those that arose in the last 50,000 years: Amber, Orange, Green and Teal.

Conforming – Amber

After the early stages, the first organisational structures originated. In the Amber-Conformist view, authority is linked to a role (like a police officer). There is one accepted right way of to do things, conforming is necessary. Some organisations, like many government institutions and schools, still see the world through ‘amber’ glasses. Thinking and doing are strictly separated. The underlying belief is that employees tend to be lazy and dishonest, and should be kept in line. Their clothes reflect their rank, they wear a social mask.

Achieving – Orange

The next organisational stage is Achievement. Here the focus shifts from conforming to achieving: the keywords are ‘winning’ and ‘competition’! This is the model of most organisations today. The view on human behaviour is that people need to be pushed, incentivised and controlled. An organisation is seen as a machine, of which the output (profit) can and should be steadily increased. And when the cogs (the people) get stuck, a soft intervention like injecting oil will solve each problem. While there is much talk about customer service, profit is more important than serving the customers.

However, the amount of freedom at this level increases. It makes use of the professional knowledge and problem-solving power in the organisation. This is done by management by objectives and by studying cause and effect. While workers are given more autonomy, managers still keep the right to formulate the strategy. However, everybody can climb the organisational ladder and become a ‘winner’.

The rise of the Achievement-Orange organisations brought prosperity to those who achieve. However, disadvantages surfaced, like the depletion of the earth and the problems in the financial sector.

Pluralistic – Green

Achievement-Orange organisations often become disconnected from their purpose and make employees feel empty and soulless. The first resistance against this occurred during the 1960s, the flower-power period. Culture-driven organisations like Ben & Jerry’s provided the answers. They operated from a socially responsible Pluralistic-Green cooperative companies with servant leaders. This was the era of equal opportunity and employee rights that still operate today.

Evolutionary – Teal

Achievement-Orange and Pluralistic-Green gave the workers much more freedom than Conformist- Amber. However, they still are not as free, agile and energetic as birds in flight. If you want that, a transition to a complete new organisational stage is needed, Evolutionary-Teal. Indeed, the rise of organisations that have at least a number of Teal or blue-green characteristics can be seen. Companies strive for more freedom, more meaning, more joy and more self-management at work, and want to operate with less harm to the natural environment.

The stages of human and organisation development at the core of the book are based on Integral Theory developed by Ken Wilber. A closely aligned and complementary theory called Spiral Dynamics originated by Professor Clare W Graves and further developed by Don Beck and Chris Cowan is also part of the ground out of which Laloux’s ideas emerged.

Laloux points out that these organisational forms did not die out with the end of each epoch but that they survive today in various organisations that operate from a “paradigm” such as Red (ie. the Mafia) or Amber (ie. Catholic Church). Each stage of consciousness can be thought of as one that was “fit” for its particular time and context. As the context changes, fitness means that “successful” evolution requires a shift from one stage to a different later stage more “fit” for the changed environment.

In his explanation on the stages of development, Laloux explains that we “get into trouble when we believe later stages are “better” than earlier stages; a more helpful interpretation is that they are “more complex” ways of dealing with the world.

Defining Characteristics of Teal Organisations

Laloux identifies three breakthroughs that characterise the organisations that are pioneers of the new Teal model of workplaces. He sees these as bold departures from current management practice:

Self-management – replace the constraints of traditional hierarchical control systems with flexible collaborative, self-organising systems. This does not mean taking the hierarchy out of an organisation and running everything democratically based on consensus. Self-management, like the previous pyramidal models, works with an interlocking set of structures and practices to support new ways of sharing information, making decisions and resolving conflict. To make self-management possible, teams are trained and coached to be effective solvers of problems and decision-makers.

Wholeness – where people are encouraged to bring emotional, intuitive and spiritual parts of themselves to work and drop the ‘social masks’ that are irrelevant and unnecessary. These new organisations create workplaces that support people’s desire to be fully themselves and build wholeness and nourishing relations.

Evolutionary purpose – collaborating with their people to unfold a future grounded in a shared purpose, leaders in these companies assume that their organisations have ‘a life and sense of direction of their own’; So rather than trying to pursue a predicted future through strategies, plans and budgets, they engage the whole organisational community to ‘listening in to their organisation’s deep creative potential…and understanding…the purpose it intends to serve’. This purpose evolves and emerges through its people and its service rather than being defined from above.

The Culture of Teal Organisations: Laloux lists the cultural characteristics of these pioneer TEAL organisations. The following sample list describes an ideal enlightened organisation and would deeply challenge many conventional organisational cultures:

- People relate to one another with an assumption of positive intent.

- Until proven wrong, trusting co-workers is the default means of engagement.

- Everyone is able to handle difficult and sensitive news.

- Everyone has a responsibility for the organisation. If someone senses that something needs to happen, he or she has a duty to address it.

- Everyone is of fundamental equal worth.

- Strive to create emotionally and spiritually safe environments.

- Failure is always a possibility if we strive boldly for our purpose.

- Don’t blame problems on others.

- Trying to predict and control the future is futile.

- In the long run, there are no trade-offs between purpose and profits.

Teal Organisations operate as a living organism or living system. They are a self-organising system of cells, without a central command system.

The Role of the Leader and Owners

Laloux argues that there are two conditions which are the only make-or-break factors. No other factors are critical to running organisations for the Evolutionary Teal paradigm.

- The CEO must drive the change. The founder or top leader must have attained and be able to act in a manner consistent with the characteristics of the TEAL developmental stage.

- The owners and Board must believe in the change and support the CEO. The owners of the organisation must understand and endorse the thinking and behaving arising out of the changes that have to be made.

Organisations can never become developed, self-managing and evolutionary organisations unless they meet these two conditions. Laloux describes how an organisation goes back to Orange when the Board is not aligned with an evolutionary CEO. So the key role of a CEO is in holding the space so that teams can self-manage. It means keeping others, like investors, from messing things up which is difficult in a short-term, market-driven economy. Laloux suggests carefully selecting investors or doing without them by financing the growth of the organisation through cash reserves and bank loans, even if it means slower growth.

In most traditional organisations it is the role of the leader to determine the vision and the strategy and then determine executive plans to get there. That way of thinking makes sense if you believe organisations are static, inanimate objects or machines. As Teal Organisations become more decentralised, the ‘top’ leader exerts less and less formal authority in developing strategy and managing its people and operations. However, simultaneously they play a vital, centralised role in ‘holding the space’ to ensure its progressive, decentralised practices do not regress back to a more traditional organisational model. Further, the CEO in all the progressive organisations were visionary leaders and played a key role in setting the vision at the highest level. They held the vision for the whole organisation even though the strategy and operational decisions were made by others.

The Rise of Mindfulness and Leaving Egos at the Door

There is much interest today in mindfulness practices in organisations. Many writers and commentators refer to this expansion of global consciousness as the ‘rise of mindfulness’. Even Wall Street banks are starting to offer their overworked bankers courses in mindfulness. Mindfulness is used as a way to help people deal with pressure, stress and unhealthy corporate cultures. It is interesting to note that the new Integral organisations weave mindfulness deeply into the fabric of the organisations. It is no longer an add-on. The organisations researched by Laloux spent considerable time talking about mindfulness.

Closely aligned to mindfulness is incorporating practices that help keep self-interest and egos at bay. At Buurtzorg staff and clients use hand symbols whenever he or she feels that someone is speaking from their ego. If someone is trying to win an argument for the sake of winning an argument, serving themselves and their career, or group, someone chimes two bells. The rule is while the bell rings everyone is supposed to be silent for a minute and ask themselves who they are trying to serve. Am I serving me? Or am I hear in service of something greater. All Team Organisations have similar meeting practices because meetings tend to be these places where egos tend to come out. Meetings without egos are only possible when people have been trained in active listening, non-violent communication.

A public school in Berlin is entirely self-managing and is very good in helping kids truly be themselves. Everyone in the school, staff and kids, gather every Friday afternoon, for 45 minutes and start by singing. Then they have a practice of open microphone, and the rule is you walk up to the microphone to thank someone or make a compliment. People tell mini-stories and what they are revealing is things about themselves. Adolescents thank their classmates for helping them in all sorts of things. The kids are daring to be authentic and vulnerable in front of 500 people. This school has no violence problems and kids are passionate to learn because they are accepted for how they are with no masks.

CASE STUDIES – INTEGRAL TEAL ORGANISATIONS

Frederic Laloux not only thinks this is possible, he describes where it is already happening. He studied 12 organisations that rely to a large extent on self-management. Examples are the Dutch neighbourhood nursing organisation ‘Buurtzorg‘, the French brass foundry FAVI and the American tomato-processing company Morning Star.

Case #1 – Buurtzorg: Since the 19th century, every neighbourhood in the Netherlands had a neighbourhood nurse who would make home visits to care for the sick and the elderly. In the 1990s, the health insurance system came up with a logical idea: why not group the neighbourhood nurses into organisations which would lead to obvious economies of scale and skill. Organisations that grouped the nurses started merging themselves, in pursuit of ever more scale. Tasks were specialised: some people would take care of intake of new patients and determine how nurses would best serve them; planners were hired to provide nurses with a daily schedule, optimising the route from patient to patient, call centre employees started taking patients’ calls, regional managers were appointed as bosses to supervise the nurses in the field. To drive up efficiency, time norms were established for each type of procedure. To keep track of this, a sticker with a barcode was placed on the door of every patient’s home and nurses scanned in the barcode, along with the “product” they delivered, after every visit. All activities were time-stamped in a central system, and could be monitored and analysed from afar.

The overall outcome proved distressing to patients and nurses alike. Patients lost the personal relationships they had with their nurse. Every day a new unknown face entered their home, and the patients – often elderly, sometimes confused – had to repeat their medical history to an unknown, hurried nurse who doesn’t have any time allotted for listening. Consequently, subtle but important cues about how a patient’s health was evolving were overlooked. The system became a machine, losing track of patients as human beings and instead seeing them as subjects to which products were applied.

Founded in 2006, Buurtzorg is causing a revolution in neighbourhood nursing. It has grown from 10 to 8,000 nurses in eight years, gaining 60% of the market share in the Netherlands while achieving extremely high patient satisfaction rates and health outcomes at 40% of the cost. At Buurtzorg nurses work in self-managed teams of 10, with each team serving a well-defined neighbourhood. They do the planning, scheduling, administration, decide which doctors and pharmacies to reach out to, monitor their own performance and decide on corrective action if productivity drops. Whenever possible, a patient always sees the same nurse. Nurses take the time to get to know the patients and their history and preferences. Care is no longer reduced to a shot or a bandage – patients can be seen and honoured in their wholeness, with attention paid not only to their physical needs, but also their emotional, relational and spiritual ones. The result is that patients are thrilled by how Buurtzorg’s nurses serve them, and so are their families who often express deep gratitude for the important role nurses come to play in the life of the sick or elderly.

By changing the model of care, Buurtzorg has accomplished a 40% reduction in hours of care per patient, which is even more impressive when you consider that nurses in Buurtzorg take time for coffee and talk with the patients, their families, and neighbours, while other nursing organisations have time “products” in minutes. Patients stay in care only half as long, heal faster, and become more autonomous. A third of emergency hospital admissions are avoided, and when a patient does need to be admitted to the hospital, the average stay is shorter. Satisfaction rates are increased for both patients and nurses. And the financial return on relationships is considerable. Ernst & Young estimates that close to €2 billion would be saved in the Netherlands every year if all home care organisations achieved Buurtzorg’s results.

Case #2 – FAVI: A French brass foundry holding a 50% market share for its gearbox forks, initially had a more traditional pyramid structure – people at the top made the decisions, workers at the bottom performed assigned tasks. Then a new CEO took the helm, and within two years the organisation was reshaped. Today the factory has over 500 employees organised in 21 teams called “mini-factories” of 15 to 35 people. Most of the teams are dedicated to a specific customer (the Volkswagen team, the Audi team, the Volvo team, etc). Each team self-organises; there is no middle management, and the staff functions have nearly all disappeared. FAVI consistently delivers high profit margins despite Chinese competition, pays salaries well above average and hasn’t had a single order delivered late in over 25 years. There are no more departments – instead the roles are divided and performed within each team. Every week in a short meeting the account manager for the Audi team shares with the team the order that the carmaker placed. Planning happens on the spot in the meeting, and the team jointly agrees on the shipment date. Decisions occur through team discussions. Account managers don’t report to heads of sales, they report to their own teams. No one gives them sales targets, their motivation is to serve their clients well and to maintain or increase the number of jobs the factory can provide. Of course coordination is often needed across teams. A group composed of one designated person from each team comes together for a few minutes – they discuss which teams are over or understaffed; back in their teams they ask for volunteers to switch teams for a shift or two. Things happen organically on a voluntary basis; nobody is being allocated to a team by a higher authority.

Case #3 – Morning Star: As the world’s largest tomato processing company, Morning Star produces over 40% of the tomato paste and diced tomatoes consumed in the US, working with 400 employees in the low season and 2,400 employees in the summer. There are 23 self-managed teams, no management positions, no HR department, and no purchasing department. Employees can make all business decisions, including buying expensive equipment on company funds, provided they have sought advice from the colleagues that will be affected or have expertise. Instead of a rigid org chart, each of the 23 teams resembles the network to the right. Morning Star is a collection of naturally dynamic hierarchies – there isn’t one formal hierarchy, there are many informal ones.

On any issue some colleagues at Morning Star will have a bigger say than others will, depending on their expertise and willingness to help. One accumulates authority by demonstrating expertise, helping peers, and adding value. So really, these organisations are anything but “flat,” a word often used for organisations with little or no hierarchy. On the contrary, they are alive and moving in all directions, allowing anyone to reach out for opportunities. Information flows more freely through the organisation, decisions are made at the point of origin, and innovations can spring up from all quarters. How high an employee reaches depends on their talents, their interests, their character, and the support they inspire from colleagues; it is no longer artificially constrained by the organisation chart. Roles and commitments are agreed upon between colleagues, and outlined in a document called a Colleague Letter of Understanding – for each role colleagues specify what it does, what authority they believe it carries (including any decision-rights), what indicators will help evaluate performance, and what improvements you hope to make on those indicators. This type of structure is appropriate for longer and more continuous processes. The key is what Morning Star calls “total responsibility” – all colleagues have the obligation to do something about an issue they sense, even when it falls outside of the scope of their roles. Often this means going to talk about the issue with the colleague whose role relates to the topic.

Limitations and Criticism

Zaid Hassan is highly critical of Re-inventing Organizations and feels there are many contradictions, such as describing the Mafia as a Red organisation since it has many of the values and behaviours of family at the core, which are very similar to the Green Family level which Laloux describes.

The book is very long and could be difficult for managers and professionals who don’t have the background or perseverance to wade through many of Laloux’s ideas. A shorter version of the key ideas would be useful.

Laloux equates self-management teams with Teal and higher consciousness. One of the authors has spent time in the Mondragon region of northern Spain, which had self-managed teams and worker cooperatives where workers own the company – Teal-like characteristics. Almost everyone smoked cigarettes and there was a strong atmosphere of male superiority. These were not very Teal organisations but were all self-managing.

Laloux doesn’t use any real scientific means to determine or estimate the level of the organisation. It seems at times, he carried the Integral Theory of stages in his mind and went out looking for organisations that he could fit to it. He doesn’t use any surveys, or other objective methods that characterise scientific studies of this topic. He also seems to be the only one who carried out this investigation which would be criticised strongly by academic examiners as a basis of research bias.

Laloux may also be confusing a ‘collective’ dimension of culture as described by Hofstede with a higher level of consciousness. In Graves’ Spiral Dynamics theory, transition to a next level involves a swing from an individual emphasis to a collective emphasis, then to an individual emphasis again. For example, the Orange Achievement level has an individual emphasis while the next level, the Green has a collective emphasis to overcome the tendency to leave out people who aren’t the achievers at the previous level. Laloux may confuse, at times, the collective green level, for a higher Teal level.

While there is some recognition that the Teal level has spiritual qualities to it, a number of the organisations Laloux describes can be considered good ‘humanistic’ organisations rather than spiritual. A characteristic of a Teal Integral organisation is that there is a recognition of a ‘Ground of Being’, an eternal essence of everyone and everything. While mindfulness and leaving ego at the door practices are steps on the right path for spiritual organisations, they are not sufficient. While there is a touch of this in some organisations, Laloux doesn’t provide much evidence that this is an engrained characteristic in the organisations he studied. The leaders of Teal organisations would have this experience and vision in their bones.

Practical Relevance

Integral theory has been around for 20 years and many consider it the best idea of the 21st century to bring together discoveries in psychology, sociology, science and philosophy. The problem with Integral Theory, however, is that it hasn’t been well translated into practical actions and seen in everyday activities, especially in leadership and the workplace. This book does a good job of translating Integral theory into organisations. By describing organisations that exist with Teal characteristics it provides tangible examples which all managers can appreciate.

This Teal model of organisations is suitable when work can be broken down in ways that teams have a high degree of autonomy. In practice, there are teams who need autonomy and will be able to govern themselves (e.g. pharmaceutical, software, consulting, marketing, etc.). The Teal Integral model is a hierarchy of purpose, complexity and scope, but not of people or power. The team at the top pursues the overall purpose of the company, while sub-teams pursue aim for parts of the overall purpose (such as research or marketing).

The evolution to becoming a self-managed Teal Organisation doesn’t happen all at once. The ideas covered in the book are possibilities that a manager can experiment with depending on the goals she is seeking. There may be opportunities for an organisation to develop a better way for employees at all levels to provide ideas and take initiative using the decision-making process. Implementing improved conflict resolution practices so that tensions are dealt with and solutions are developed between the parties involved can save senior managers time and lead to better solutions. Adopting practices to bring more wholeness into the workplace could improve employee satisfaction and make teams more effective. The important thing is to decide what works best for your organisation.

Summary

This book is essential for anyone interested in how businesses and organisations might evolve and thrive in an increasingly volatile, ambiguous and complex world. It provides a simple path to a new model and points to the need for coaches and those of us influencing the future of business and organisations to pay attention to their own levels of development. It is not possible for manager, consultant, coach or mentor at an earlier stage of development to lead another person, team or organisation to a higher level. There is therefore a significant need for consultants, coaches and leaders to pay attention not only to the developmental stage of their clients and staff but to consider whether they have arrived at a sufficiently advanced stage themselves to contribute to integral development.

The book is a stimulating read since it demonstrates many examples how organisations can thrive while swimming against the tide of instrumentalist and shareholder-value-driven bureaucracy. It provides substantial detail on the structures, practices and processes the organisations adopt to encourage human development and sustainability. Employees are encouraged to find their own roles and play to their strengths. Decisions are taken by peer groups rather than by leaders, or often by individuals acting simply on advice from relevant colleagues, with the consequence that corporate headquarters’ are largely redundant. Employees are trusted rather than controlled to do the right thing, so that cumbersome compliance practices are no longer needed.

Laloux’s book is very timely as in the years since the financial crisis public distrust has been growing not just in the leaders of the financial organizations that led us into the financial crash of 2007-8 but also failures of leadership in sectors as diverse as the health service, the media, supermarkets, the police and government. The exciting thing about Laloux’s book is the detailed portrayal it presents of successful companies and organisations that are making real today the model of tomorrow. Laloux sees the forces for change being driven not only by the collapse of the existing order but by a fundamental evolutionary shift in human development, the kind of shift that occurs as human consciousness develops towards the higher stages of consciousness as described in many of the developmental theories of Kegan, Torbert, Wilber, Beck and other authors.

Laloux also gives an excellent example of trust himself. You can download his book on the website shown below: www.reinventingorganizations.com for free or you pay what you feel is right (which is very Integral thinking)!

About the Authors

Ron Cacioppe is the Founder and Chairman of Integral Development, a leadership and organization development company in Western Australia. Ron also is the Visiting Professor at the Antioch University in the Graduate School of Leadership and Change in the Ph.D. program and is currently living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Ron has been a Professor of Leadership at the University of Western Australia and runs mindfulness and leadership development programs in the workplace. He is Deputy Chairman of the not-for-profit Integral Leadership Institute and helped start the Zen Group of Western Australia.

Michael Fox is a senior consultant and coach with Integral Development. Michael holds a BPsych, B.Sc, and MPS. Michael was the Chairman of the Integral Institute Australia and has been involved for over 15 years applying integral theory to leadership. He specialises in leadership development, strategic planning and psychological and organisational assessment and works with clients from mining, financial services, IT, health, human services and education.

[…] una mayor compresión de este tipo de modelo, recomiendo la lectura de Reinventing the Organizations de Frederic Laloux. En su libro, las organizaciones que aquí yo llamo convencionales, serían del tipo naranja y del […]