4/22 – Challenges of Transdisciplinary Collaboration: A Conceptual Literature Review

Sue L. T. McGregor

Sue L.T. McGregor

Sue L.T. McGregor

The focus of this paper was transdisciplinary collaboration and what is being said in the literature about the challenges of this aspect of transdisciplinarity work. A conceptual literature review revealed four conceptual threads: (a) managing group processes, (b) reflexivity, (c) common learning process, and (d) facilitating integration and synthesis. These challenges mirror the special qualities of transdisciplinary collaboration. Individual and collective diversities deeply affect communications and collaborations during transdisciplinary work. Those engaged in such work can benefit from the results of conceptual literature reviews, which help map the terrain of particular phenomenon; in this case, transdisciplinary collaboration.

Introduction

Transdisciplinary approaches to complex global problems are gaining momentum, if not yet mainstream (Lawrence, 2015). The essence of transdisciplinarity is the cooperation and collaboration of a collection of diverse actors who normally do not work together yet are mutually concerned for transdisciplinary problems. Some examples are climate change, poverty and inequalities, unsustainability, uneven growth and development, human aggression, uneven income and wealth distribution, population growth, the human condition, and any issue with global implications (McGregor, 2009). No one perspective, discipline, or world view constitutes a privileged place from which to understand the world or these intractable problems (Nicolescu, 2010, 2014). Respecting this assertion, transdisciplinarity “is about dialogue and engagement across ideologies, scientific, religious, economic, political and philosophical lines” (Shrivastava & Ivanaj, 2011, p. 85).

For the past 50 years, scholars have mainly focused on developing the transdisciplinary approach from three perspectives: philosophically, theoretically, and conceptually (for examples of these efforts see Darbellay, 2015; Klein et al., 2001; McGregor, 2015; Nicolescu, 2002, 2011, 2014). Beyond these abstract initiatives, transdisciplinarity is now being implemented in practice, including research, policy development, practical (on-the-ground) problem solving, curriculum development, and entrepreneurial initiatives (e.g., Du Plessis, Sehume, & Martin, 2013; Hirsch Hadorn et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2001; Leavy, 2011; Pohl & Hirsch Hadorn, 2007; Shrivastava & Ivanaj, 2011).

One of the main challenges of addressing the complexity of the world from a transdisciplinary perspective is respecting individual and collective diversities, for these deeply affect communications before and during collaborations (Dincã, 2011; Pohl & Hirsch Hadron, 2008). Given that a heterogeneous collection of people is trying to address complex situations from different ideologies, mindsets, value sets, agendas, power positions, perspectives, and interests, working together can be a profound challenge. To that end, the goal of this research was to identify and synthesize ideas from the transdisciplinary literature about the key aspects affecting transdisciplinary collaboration, and do so by conducting a conceptual literature review.

Special Qualities of Transdisciplinary Collaboration

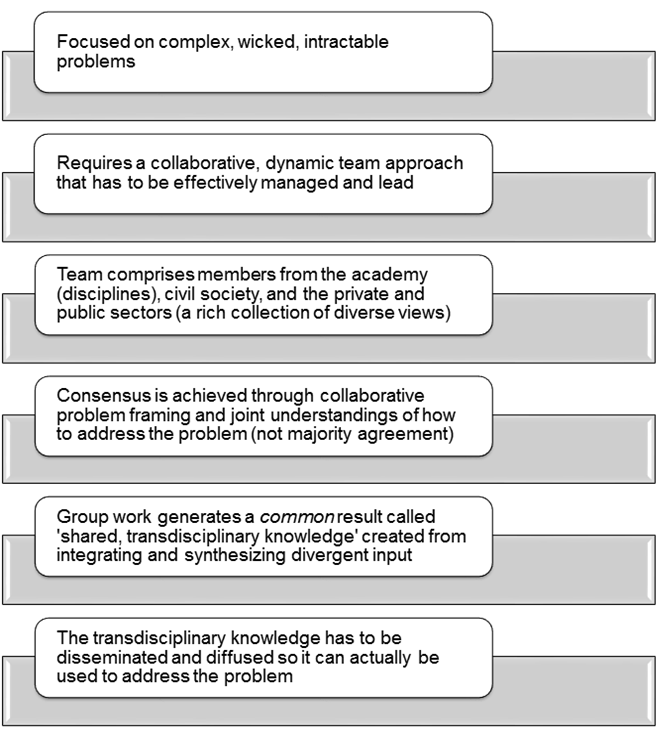

Transdisciplinary collaborative work has several special qualities (see Figure 1). First, it is focused on complex, wicked problems of the life-world. Examples are poverty and inequalities, hunger, violence, disease, unsustainability, and uneven wealth and income distribution. Their solution necessitates the integration of life-world and local expert perspectives and scientific/disciplinary perspectives. These life-world problems are especially relevant for those experiencing the issue or those dealing with the fallout and consequences of it being inadequately addressed. Normally, there is a society-wide interest in improving the situation, but the best way to do so is in dispute. And unfortunately, any attempts to solve these problems often create new problems, yet but everyone feels something must be done (Brown, Harris, & Russell, 2010; Pohl & Hirsch Hadron, 2008; McGregor, 2012).

Figure 1: Special qualities of transdisciplinary collaboration

Second, transdisciplinary is a collaborative, team-approach. Transdisciplinary results are achieved by effectively dealing with different people holding different worldviews. A one-person approach would involve one person integrating multidisciplinary and/or sectoral perspectives into their personal worldview. Team work is much more challenging because ill-managed or unrecognized ideological, value, or opinion differences can hinder collaboration. The work of the team has to be moderated so everyone can participate and actively (a) contribute to answering the research question or addressing the problem, (b) help to reprocess and translate emergent knowledge, and (c) ensure group coherence (i.e., holding together to create a whole) (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015; Klein, 2008; Pohl & Hirsch Hadron, 2008).

Third, transdisciplinary teams comprise diverse members from different disciplines working with future users who will use the results in their professional or everyday life. These future users are intricate to the research project. They contribute substantially to the research process, assuming far more than an information source, consultancy, or a feedback role (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015). Rather than just disciplinary teams, transdisciplinary collaborative work involves disciplinary-sector teams, including the private sector (industries and businesses), civil society, and public agencies (governments). Instead of university scholars determining the research questions and research design, these decisions are made jointly (Pohl & Hirsch Hadorn, 2008).

Fourth, transdisciplinary work depends on a consensus, but not the lay notion of majority agreement. A transdisciplinary consensus entails the research team arriving at a shared framing of the problem, agreed-to objectives they all equally want to reach, shared questions, and a joint understanding of how to answer the questions (or at least the need to address the issue). This consensus often involves the development of a common language emerging out of the team work. This type of consensus requires “collaborative problem framing” (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015, p. 125). For clarification, a shared point of view is not the same thing as an identical point of view. All participants can hold onto their own worldview (identity), but they must be prepared to link the team’s integrative perspective into their own identity (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015). Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn (2008) called this “mutual learning” (p.114), arguing that the core challenge of transdisciplinary research is concurrently understanding the diverse scientific and societal views of problems while integrating diverse insights.

Fifth, transdisciplinary work yields integrated results, or “a common result” (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015, p. 125). The research project or transdisciplinary enterprise culminates in a synthesis of “reprocessed, related and brought together” contributions emergent during the team work. “The common result is the integrated knowledge produced in this process; this so-called ‘synthesis’” (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015, p. 125). The shared result does not reflect the addition of all individual contributions; rather, the final whole (a transdisciplinary result) is greater than the sum of all of the contributory parts (Lozano, 2014). Solutions to the problem are “more comprehensive than the single contributions and are shared by all” (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015, p. 125).

Sixth, the results of the transdisciplinary team work have to be disseminated and diffused to relevant audiences, who in turn have to promote and apply them. Because the team comprises academics and non-academics, channels of information and knowledge dissemination have to be developed to reach all target audiences (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015). Actually, transdisciplinary knowledge is diffused during its creation (because the end (future) users are co-creating it) and afterwards, through both formal disciplinary channels (conferences, journal articles), and informal knowledge dissemination channels. Diffusion can also happen when the original team partners start working on different life-world problems in a new context (Klein et al., 2001). Nicolescu (2011) goes further, positing that the resultant transdisciplinary knowledge is alive and in flux, because those co-creating it are alive and always changing as the team work unfolds.

Method

To achieve the research goal, a conceptual literature review was conducted. This differs from a systematic review of the literature, which is anchored to a defined research question. The only literature that is reviewed is that concerned with the research question. Conversely, a conceptual review helps scholars “gain new insights into an issue,” and permits them to selectively review literature (Kennedy, 2007, p. 139). Because conceptual reviews “lack a ‘system,’ they have the flexibility to address the complexity of the substantive issue [being studied]” (Kennedy, 2007, p.146) (see also Findley, 1989).

In more detail, a conceptual literature review maps the terrain around a chosen phenomenon, in this case, the challenges to transdisciplinary collaboration. Such reviews draw from a wide range of different sources (Dohn, 2010) so as to thoroughly examine the literature streams relevant to a specific idea (McMillan, Moris, & Atchley, 2011). Conceptual reviews enable researchers to synthesize areas of knowledge in an integrated fashion, leading to more clarity, better understandings, and new insights into a phenomenon (Close, Dixit, & Malhotra, 2005; Findley, 1989; Jesson, Matheson, & Lacey, 2011; Kennedy, 2007; Petticrew & Roberts, 2005; Solway, Camic, Thomson, & Chatterjee, 2016). They serve as much needed summaries and time-savers for researchers, professionals, practitioners, and academics because they produce a central resource, a point of reference, for future work on the topic (Close et al., 2005).

When approaching a conceptual literature review, it is common for the researcher to already have several important articles at hand. These pieces are used as springboards for a broader search (Findley, 1989). As an example, the researcher was familiar with Polk’s (2015) article which identified five overarching concerns about the key challenges to transdisciplinary collaboration. Three pertain to the group itself (inclusion in the group, collaboration, and group reflexivity), and two to the knowledge shared and created (integration, and usability). These focal areas are central to transdisciplinary work. They promote “the in-depth participation of both researchers and stakeholders in the entire [transdisciplinary] knowledge production process” (Polk, 205, p. 113).

In more detail, an array of different stakeholders is entitled to be included in transdisciplinary work. Through working jointly, the group benefits from a high degree and quality of participation via collaborative processes and methods. To work best, this collaborative work is characterized by reflexivity, which Polk defined as “on-going scrutiny of the choices that are made when identifying and integrating diverse values, priorities, worldviews, expertise and knowledge” (2015, p. 114). Collaborative reflexivity better ensures the integration and synthesis (assimilation and combination) of both academic and real-world contributions and perspectives, leading to useful transdisciplinary knowledge. Usability refers to the social robustness and transformative capacity of the transdisciplinary group’s outputs and outcomes. The social robustness of emergent transdisciplinary knowledge and boundary objects are continually assessed and reflected upon during the group’s work (Polk, 2015, see also Penker & Muhar, 2015).

Although a conceptual review can and should use literature selectively (Findley, 1989; Kennedy, 2007), the review should also ensure that a relatively complete census of relevant literature is accumulated. The literature review is nearing completion when new ideas cease to emerge, called conceptual saturation (Dohn, 2010; Webster & Watson, 2002). These premises and research protocols and strategies were employed in this study. Rather than inventorying the documents gleaned from this process, results of the conceptual literature review will be shared in a narrative, organized by the most common conceptual threads emergent from the literature.

Results of Conceptual Literature Review

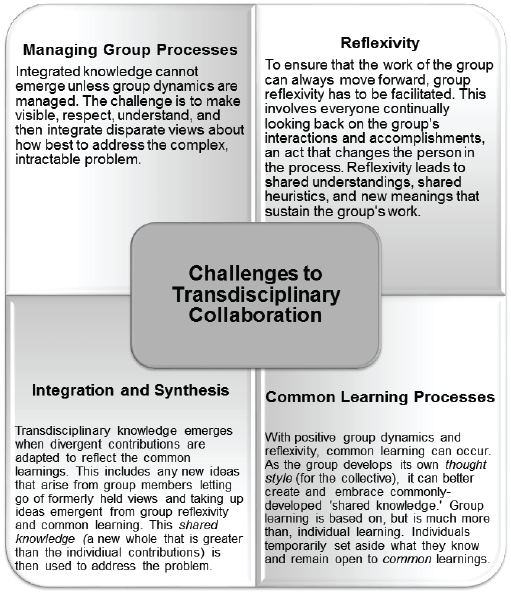

Conceptual literature reviews provide a comprehensive review of existing literature on a topic. The results help people understand how the literature conceptually frames a phenomenon. The understandings derived from individual studies found in the literature are identified and merged into a more comprehensive conceptual understanding (Proitz, Mausethagen, & Skedsmo, 2015). This conceptual literature review identified four key challenges to transdisciplinary collaboration: (a) managing group processes, (b) reflexivity, (c) common learning process, and (d) facilitating integration and synthesis (see Figure 2). These conceptual threads reflect Polk’s (2015) aforementioned five challenges: inclusion in the group, collaboration within a group, group reflexivity, and knowledge integration, and knowledge usability.

Figure 2: Results: Challenges to transdisciplinary collaboration

Managing Group Processes

Defila and Di Giulio (2015, p. 124) characterized the management of transdisciplinary work as “genuinely creative and scientific work.” Schauppenlehner-Kloyber and Penker (2015) claimed that managing participatory group processes is one of the main challenges of transdisciplinary enterprises. It is a highly demanding task without which transdisciplinary collaborative work cannot happen. Transdisciplinarity’s intractable problems are “intertwined with [the] sociopolitical context, and require participation of stakeholders to generate socially accepted outcomes” (Carew & Wickson, 2010, p. 1146). Because transdisciplinary work intentionally involves many stakeholders from diverse backgrounds, collaboration and group processes have to be effectively managed (Wickson, Carew, & Russell, 2006). “Group processes running out of control can seriously endanger transdisciplinary research [and work]” (Penker & Muhar, 2015, p. 143).

Key aspects of collaboration. Newig (2007) indicated that group processes can be more effectively managed if several key aspects of collaboration are accounted for: fairness of any procedures, transparency of the process, open communications, early involvement, joint determination of process rules, impartiality of mediation, and openness regarding any decisions to be made within and by the group. Failure to account for these issues compromises group dynamics, and, by association, the extent and quality of transdisciplinary collaboration.

Group dynamics. Indeed, Schauppenlehner-Kloyber and Penker (2015) added group dynamics as a key factor of effective collaboration, predicated on the assumption that transdisciplinary groups move through four stages: (a) the latent and informal emergence of a need, and then an explicit call, for transdisciplinary work; (b) collaborative problem framing and team building; (c) co-production of solution-oriented and transferable knowledge; and, (d) the integration and application of the knowledge produced. They explained that the process starts with individual needs, shifts to group needs (establishing rules and norms), and ends with task needs (working together).

Appreciating that information is relatively easy to transfer between participating parties, group dynamics make it much more difficult for new, co-produced knowledge to emerge, and be shared and applied. The latter require group learning processes, which involve “a shift in values, structures and processes and lead to empowerment for self-organised action” (Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, 2015, p. 69). In addition to information and knowledge, transdisciplinary collaboration may also have to include social, cultural, aesthetic, spiritual, and religious considerations (Baturalp, 2015; Nicolescu, 2014). Effective group dynamics better ensure that a new culture of learning and interaction emerges, along with new competencies and shared values. These dynamics require people who are experienced in leading group processes, whether they are team members or external facilitators (Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, 2015).

Transdisciplinary group developmental stages. Transdisciplinary groups, and their attendant dynamics, tend to progress through five developmental stages. First, those who are involved have to come together for the first time (forming), and orient and familiarize themselves with each other and the purpose of working together. Second, at the conflict stage, members of the group move through power struggles as they get to know each other, hopefully well enough to continue working together (storming). Stage two helps form the basis for team cohesiveness in that people deal with disagreements, resistance, defensiveness, unsureness, and vested concerns. It entails role clarity, identifying and accepting personal differences, and dealing with conflicts so the group can move ahead (Jagues & Salmon, 2007; Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, 2015). Penker and Muhar (2015) said that those involved “must not underestimate the fundamental trade-offs between legitimacy, scientific credibility and societal impact, which sometimes require active mediation by boundary organizations bridging science and society” (p. 143).

At the third stage, norming, a sense of common identity and purpose begin to emerge, manifested in growing consensus, cohesion, and comfortableness with each other. People are at ease accepting responsibility for their contributions. Eventually, if group dynamics remain positive, the group starts performing together, working smoothly as a unit, with shared goals, norms, and a good atmosphere. At this fourth stage, people experience a sense of constructive belonging, interdependence, empathy, a sense of satisfaction, and a high commitment to the transdisciplinary process. At the final stage, adjourning, the group dissolves either because it accomplished its goals or because members lost interest, motivation or could no longer work together. If goals were accomplished, group members will feel empowered to engage in transformative action, especially if they have been reflexive as a group, and appreciative of each other’s efforts. People will ultimately disengage from their forged relationships with mixed emotions as they transition away from the group (Jagues & Salmon, 2007; Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, 2015).

Factors influencing group dynamics. Acknowledging these group formation stages, Collins and Fillery-Travis (2015) recommended team coaching as a way to ensure that the substantial psychological investment required to join a transdisciplinary team is respected. Team coaching makes it easier to bring together and integrate insights from a collection of diverse but vested actors. These powerful group dynamics are influenced by several key factors (Godemann, 2011). First, the size and constancy of the group matters. The ideal size seems to be between 4-12 members, and the more constant the number stays, the higher the chance of group integration and positive dynamics. Also, the group must be representative and people must have legitimate reasons to be involved (Penker & Muhar, 2015).

Second, the more experienced people are with transdisciplinary group work, the better the communication and the collaboration. Third, the more balanced the power relationships, and the more even the group members’ status, the more positive the group dynamics. Fourth, the higher the degree of familiarity among group members, the better the chance for meta-knowledge to form; that is, members can learn about each other’s expertise. Fifth, group dynamics are further improved if the group exhibits strong group reflexivity (i.e., meta-reflection), defined as their ability to (a) reflect on the transdisciplinary group’s objectives, strategies, and processes, coupled with their ability to (b) use this knowledge to adapt to their context and circumstances. Complex problems (uncertainty and ambiguity) require group self-reflexivity (Godemann, 2011; Penker & Muhar, 2015).

Sixth, group dynamics are deeply shaped by the members’ willingness to share information and their knowledge so it can be transformed into co-created transdisciplinary knowledge. Hand-in-hand with this factor is the requirement that the group cover all relevant expertise and insights. Finally, the management and communicative skills of the self-selected or delegated group leader affect group dynamics. The latter are improved if the leader is skilled at identifying and then integrating participants’ perspectives, values, and worldviews (Godemann, 2011; Penker & Muhar, 2015).

Cognitive and social factors. Transdisciplinary collaboration involves the interaction of both cognitive and social factors. Klein (2008) explained that “[i]ntellectual integration is leveraged socially through mutual learning and joint activities that foster common assessments. Mutual knowledge emerges as novel insights are generated, … relationships [are] redefined, and integrative frameworks built” (p.119). Leveraging integration entails weaving perspectives together into a new whole, reaching effective synthesis. In order for cognitive and social factors to interact, transdisciplinary teams have to manage conflicting approaches; clarify and negotiate stakeholders’ differences; compromise; communicate in a systematic fashion; and, engage in mutual, common, and joint learning activities (Baturalp, 2014; Klein, 2008).

Reflexivity

Transdisciplinary collaborative work must especially accommodate reflexivity, a key aspect of group dynamics. Reflexivity is a two-way relationship between something. It refers to an act of self-reference where the act of reflecting on something or examining it affects the person who is reflecting or instigated the examination (see Wickson et al. (2006), who distinguish it from personal reflection). In social processes like transdisciplinary group work, reflexivity is a “collaborative process of acknowledgement, critical deliberation and mutual learning on values, assumptions and understandings” that enable members of the group to create new meanings, new rules for interacting with each other (heuristics), and new identities within the transdisciplinary group (Popa, Guillermin, & Dedeurwaerdere, 2015, p. 47).

Four features of reflexivity. The main purpose of transdisciplinary work is to bring reflexivity into processes of knowledge production. In transdisciplinary group work, knowledge building has “an active, experimental and social character” making it imperative that reflexivity is accommodated (Popa et al., 2015, p. 48). They proposed that transdisciplinary reflexivity has four features. First, collaborative deliberation is emphasized while group members build a shared understanding of the overall epistemic (validity of knowledge) and normative orientation of their work. Transdisciplinary knowledge is validated through an iterative and adaptive process that involves social (common) learning and the confrontation of different, reasoned perspectives.

Second, reflexivity underpins the process of framing socially relevant problems. Members of transdisciplinary teams confront particular social contexts, and strive to innovate through mutual learning and the co-production of knowledge. Framing a socially relevant problem entails assuming a critical stance toward fellow members’ understandings, values and assumptions. The goal is to achieve critical awareness by engaging in reasoned, jointly-agreed-to normative orientations, ideally leading to critical, transformative action (Popa et al., 2015).

The third feature of transdisciplinary reflexivity is social experimentation and social learning processes. Because transdisciplinary knowledge creation has an experimental and social character, team members need to appreciate that co-production of knowledge is “a socially-mediated process of [concrete] problem solving based on experimentation, learning and context specificity” (Popa et al., 2015, p. 48). Finally, transdisciplinary reflexivity depends on the critical and transformational aspects of collaboration. This includes both the acknowledgment of values, ideologies and power structures (i.e., normative commitments) as well as attempts to clarify and build an explicit agenda of sustainable change to address the socially relevant problem (Popa et al., 2015).

Common Learning Process

Transdisciplinary work is often said to involve a common learning process; that is, people working together on transdisciplinary problems have to find a process that works for them so they can learn in common (Kläy, Zimmermann, & Schneider, 2015). This process helps them collaboratively build new transdisciplinary knowledge that can be used to address the complex problem. Yeung (2015) coined the term transdisciplinary learning, which happens at the intersection where stakeholders are engaged in transdisciplinary collaboration. Each respective stakeholder’s knowledge is transferred from one to the other. As these diverse perspectives are processed, common learning occurs.

Thought styles. Common learning happens when the group achieves a “thought collective,” or a common “thought style” all their own (Kläy et al., 2015, p. 76). Members of the transdisciplinary group retain their own disciplinary or sector-specific identity while embracing a commonly-developed thought style unique to this group. For clarification, transdisciplinary thought styles facilitate going beyond disciplinary or societal boundaries to develop original problem solving trajectories for the creation of hybrid knowledge. Transdisciplinary teams work at the boundaries while constantly reconfiguring them. They co-construct a negotiated and shared knowledge though the act of transdisciplinary intelligence, understood to be the linking of ideas with each other. Thought styles facilitate the production and integration of ideas on the interface between disparate stakeholders (Darbellay, 2015), possible because of the common learning process.

Common learning. Learning by itself “involves the enrichment of existing knowledge and the creation of new knowledge” (Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, 2015, p. 62). Common, social learning takes this further by including collective engagement and interaction with others thereby fostering the co-creation of transdisciplinary knowledge, and the means required to transform a problematic situation (Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, 2015). In this process, members of the group remain themselves while at the same time understanding the others, and making progress with them toward a common understanding (i.e., a common learning) (Kläy et al., 2015). Individual learning forms the vital base for group learning, whereby “the combined intelligence in the team exceeds the sum of the intelligence of its individuals, and the team develops extraordinary capacities for collaborative [learning and] action” (Lozano, 2014, p. 209). In this case, extraordinary means beyond what is normal for each individual group member.

Four factors shaping common learning. Four factors can affect this common learning process, called I, We, It, and Globe. Respectively, this refers to each individual group member, the interactions amongst members, the central concern or focus of their work, and the larger environment and context within which the transdisciplinary work is happening. Each person brings their interests and needs to the enterprise, and these feed into and shape the relational patterns amongst the team members. The intractable issue bringing them all together is worked on in a framework created by the group’s leader as well as its members. The latter include any physical, virtual, social, political, and temporal environment, conditions, and circumstances deeply affecting the collaborative enterprise (Jagues & Salmon, 2007; Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, 2015). When these four factors are effectively managed, they facilitate “social learning, cooperation, transparent interaction and growth-enhancing communication” (Schauppenlehner-Kloyber & Penker, 2015, p. 61).

Unlearning to learn in common. In order for common learning to occur during transdisciplinary work, team members have to unlearn many things, a collaborative offering that requires humility and modesty. They have to be willing to “temporarily divest themselves of their academic [or sector-oriented] habits and the power that goes with these habits” (Kläy et al., 2015, p. 77). During this unlearning process, the common concern bringing them all together (e.g., climate change) helps members overcome “the initial disorientation resulting from the diversity of perspectives” (p. 77). In summary, common learning requires that group members be guided by a common concern, acknowledge their diversity, and be willing to work together to build an atmosphere of respect for temporarily setting aside respective perspectives (Kläy et al., 2015).

Facilitating Integration and Synthesis

Transdisciplinary knowledge (the common result of collaboration) cannot emerge from collaborative enterprises unless the integration and synthesis of divergent contributions to addressing the problem is facilitated. Both disciplinary knowledge and non-academic knowledge (also called life-world or local expert knowledge) should be taken into account when new knowledge from the transdisciplinary enterprise is synthesized. This goal can be compromised. An example is occasions when non-academic knowledge informs the design of a transdisciplinary project but is excluded when creating ‘integrated knowing.’ Another example is when non-academic knowledge is ignored when the joint enterprise is initiated, but expected to be used when the common result is created (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015; Pohl & Hirsch Hadorn, 2008).

Focus on worldviews. When it comes to knowledge integration, those involved have to (a) detect potentially relevant contributions, (b) uncover and relate worldviews, and (c) possibly reprocess results so they can be synthesized into new knowledge. These tasks involve those who were involved in the transdisciplinary enterprise and/or those who are tasked with integrating the outcomes. These may or may not be the same people. The integration of disparate worldviews requires that they first be made visible. Once exposed, those involved can perceive them, thereby acknowledging and unlocking their potential to inform or impair the common result (i.e., the new transdisciplinary knowledge) (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015). Each of disciplinary and local expert knowledge, values, worldviews, and interests have to be integrated (Penker & Muhar, 2015).

Typology of integration approaches. Defila and Di Giulio (2015) suggested that Rossini and Porter’s (1981) typology of four approaches to integration is the only one that is actually used in transdisciplinary research (see also Pohl & Hirsch Hadorn, 2008): common group learning, system (group modelling), negotiation, and delegation (integration by leader), with a fifth approach, collective intelligence, added by Cunningham (2009). In more detail, common group learning best ensures a consensus with the final outcome (the new transdisciplinary knowledge). With this approach to integration, knowledge is generated by the group that acts and learns as a whole. The output of their interactions is a common intellectual product (i.e., a body of integrated knowledge), which is owned and used by the group.

The common group modelling approach to integration best ensures eventual agreement on the outcome. Those involved in the enterprise create one or more models (like decision trees or flowcharts) that mediate the co-production of new knowledge. They provide a platform upon which to integrate the dynamics that will shape the outcome (Rossini & Porter, 1981). If the transdisciplinary enterprise demands equal participation by all stakeholders, the negotiation approach is preferred. To respect this tenet, those involved will work to create a structure that involves negotiation amongst academic and non-academic experts, all the while balancing self-interests (i.e., turfs) with substantive knowledge. Other scholars agree, recognizing that transdisciplinary learning is based on equal dignity and right relationships (Hartling, Linder, Britton, & Spalthoff, 2013). This approach helps ensure broad-based support for the final integrated product (but does so at the expense of full integration) (Rossini & Porter, 1981).

The integration by leader approach (also called delegation) comes into play when a designated leader of the transdisciplinary exercise assumes the task of integrating all aspects of the work. The integrated outcome usually lacks depth because it is almost impossible for the leader to be familiar with all aspects of the work, which were delegated to people who worked alone instead of together (Rossini & Porter, 1981).

In 2009, Cunningham tendered the collective intelligence approach to knowledge integration. In these instances, integration is facilitated by the Internet, meaning interactions among individuals can happen in different locations, often asynchronously (i.e., at different times). While leveraging a vast amount of information, this approach runs the risk of too much information, leading to compromised knowledge integration. It is also difficult to deal with divergent worldviews, threatening a unified acceptance of the final integrated product. Brown and Harris (2015) referred to the “emergence of the collective mind” (p. 179) during transdisciplinary work. By this they meant that all minds engaged in the group are informing each other, ultimately without barriers or borders. The resultant integration creates transdisciplinary knowledge.

Often used in combination, these five approaches to integration are complementary rather than mutually exclusive (Defila & Di Giulio, 2015). Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn (2008) added that integration requires participants to be open to each other’s insights, cultures, knowledge, paradigms, practices, and discourses. They have to let these things “feed into and be transformed during a transdisciplinary” enterprise (p. 112). This can happen when stakeholders remain open to “relativizing one’s own perspective and accepting other viewpoints as equally relevant. [When this happens], the perspectives can begin to interact. In this second step of integration or synthesis, researchers’ and actors’ perceptions are interrelated and combined to develop knowledge and practices that help to solve the problem by promoting what is perceived to be the common good” (Pohl & Hirsch Hadorn, 2008, p. 115).

Four strategies to facilitate integration. Like Defila and Di Giulio (2015), Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn (2008) also recommended that transdisciplinary stakeholders turn to Rossini and Porter’s (1981) typology of integration, an act that can be enriched by using one of four recommended integration facilitation strategies. First, to ensure mutual understanding, those involved can jointly create a glossary of terms, or agree to use everyday language, and to avoid scientific or practice-specific terms. Second, integration can also be facilitated by creating or restructuring the meaning of theoretical or conceptual terms. This may involve co-creating bridging concepts, mutually adapting concepts and their operationalization in respective contexts, or both. Third, participants can create models that facilitate shared understandings and mutual learning. Finally, participants can agree that they will collaboratively create a product through the process of integration (i.e., a boundary object jointly created at the interface of academic and life world actors). All of these strategies depend on a deep knowledge of one another’s positions, and a flexible attitude regarding one’s own position (i.e., be willing to change) (Pohl & Hirsch Hadorn, 2008).

Recursive model for knowledge integration. The integration of diverse knowledge requires respect for the role of both abstract (academic-based) knowledge and case-specific (real world, local expert) knowledge. Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn (2008) recommended that transdisciplinary enterprises should employ a recursive model, with recursive meaning repeating things. As participants strive to validate the newly integrated knowledge in real world settings, they have to account for “the complexity of problems and the diversity of perceptions” (p. 117). This recursive approach helps the work move forward. It ensures that people are not stymied by the preliminary state of knowledge when coming into and moving through the transdisciplinary integrative process. The recursive approach to integrating or synthesizing knowledge is based on “learning to be reflexive together, that is the people who pose the problems, those who are implicated in the problems and those who help deal with them” (p. 117).

Three levels of integration. Integration is the crux of transdisciplinary team work (Klein, 2008). It can happen on three levels (Wickson et al., 2006). First, members of the transdisciplinary team can integrate knowledge from different disciplines. But boundaries between the disciplines now operate in concert with the processes of cross fertilization, alliances, and the cross-pollination of ideas and skills (Songca, 2006).

Appreciating that integration at disciplinary boundaries may not be enough anymore, the transdisciplinary team can, second, achieve integration by embedding stakeholders in the problem being examined. Instead of being an outside observer, all members of the team would experience the problem first hand (Wickson et al., 2006).

Third, the team can strive for transdisciplinary praxis whereby they remake and/or reinterpret abstract theory and disciplinary knowledge through insights gained in concrete practice and vice versa; that is, they inform each other. This approach reflects a richer notion of transdisciplinarity, a merging of disciplinary and societal knowing, and can be informed by embedded stakeholders (Wickson et al., 2006).

Conclusions

Conceptual literature reviews serve to help map the terrain of a particular phenomenon. They produce a centralized collection of synthesized ideas, which act as a point of reference for others interested in the topic. This conceptual literature review was about the most challenging aspects of transdisciplinarity collaboration. It revealed four overarching issues: (a) managing group processes, (b) reflexivity, (c) the common learning process, and (d) facilitating integration and synthesis (see Figure 2). The results show that the transdisciplinary literature is engaging with how best to ensure that collaborations accommodate the special qualities of transdisciplinary work (see Figure 1).

“Transdisciplinary collaborative knowledge synthesis” comes from integrating the information and ideas shared by a number of experts (disciplinary and local actors). In order to have effective activities in an inclusive setting, the group has to work through an intensive and ongoing collaboration. This effort ensures they can adapt to the increasing complexity of their interactions. The actors are “dissimilar in several characteristics,” making it crucial that the group captures everyone’s perspectives and input so they can be integrated into the final common result (Baturalp, 2014, p. 248).

Individual and collective diversities deeply affect communications and collaborations during transdisciplinary work. Those engaged in such work can benefit from the results of conceptual literature reviews, which contain synthesized data from selective literature. In the future, other scholars should conduct similar reviews to help build a richer map of the transdisciplinary collaboration terrain. Publishing such reviews will make the concepts, challenges, and approaches to transdisciplinary collaboration more accessible for critique, application, adaptation, and implementation (Penker & Muhar, 2015).

About the Author

Sue L. T. McGregor, PhD is a Canadian home economist (40 years) at Mount Saint Vincent University, Canada (retired) . She was a Professor in the Faculty of Education. She is Associate Editor for the Integral Leadership Review with a focus on Transdisciplinarity. Her intellectual work pushes the boundaries of consumer studies and home economics philosophy and leadership towards integral, transdisciplinary, complexity and moral imperatives. She is Docent in Home Economics at the University of Helsinki, a Kappa Omicron Nu Research Fellow (leadership), an The ATLAS Transdisciplinary Fellow, and an Associate Member of Sustainability Frontiers. Affiliated with 19 professional journals, she is Associate Editor of two home economics journals and part of the Editorial Team for Integral Leadership Review. Sue has delivered 35 keynotes and invited talks in 15 countries and published over 150 peer-reviewed publications, 21 book chapters, and 9 monographs. She published Transformative Practice in 2006. Consumer Moral Leadership was released in 2010. With Russ Volckmann, she co-published Transversity in 2011 and, in 2012, she co-edited The Next 100 Years: Creating Home Economics Futures. Her professional and scholarly work is available at http://www.consultmcgregor.com

References

Baturalp, T. B. (2014). Transdisciplinary collaboration in designing patient handling/transfer assistive devices: Current and future designs. In B. Nicolescu & A. Ertas (Eds.), Transdisciplinary education, philosophy and applications (pp. 235-253). Austin, TX: TheAtlas Publishing.

Brown, V. A., & Harris, J. A. (2015). The emergence of the collective mind. In P. Gibbs (Ed.). Transdisciplinary professional learning and practice (pp.179-195). New York, NY: Springer.

Brown, V. A., Harris, J. A., & Russell, J. (2010). Tackling wicked problems: Through the transdisciplinary imagination. New York, NY: Earthscan.

Carew, A. L., & Wickson, F. (2010). The TD wheel: A heuristic to shape, support and evaluate transdisciplinary research. Futures, 42(10), 1146-1155.

Close, A. G., Dixit, A., & Malhotra, N. K. (2005). Chalkboards to cybercourses: The Internet and marketing education. Marketing Education Review, 15(2), 81-94.

Collins, R., & Fillery-Travis, A. (2015). Transdisciplinary problems: The teams addressing them and their support through team coaching. In P. Gibbs (Ed.). Transdisciplinary professional learning and practice (pp.41-52). New York, NY: Springer.

Cunningham, S. W. (2009). Analysis for radical design. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 76(19), 1138-1149.

Darbellay, F. (2015). Rethinking inter-and transdisciplinarity: Undisciplined knowledge and the emergence of a new thought style. Futures, 65(1), 163-174.

Defila, R., & Di Giulio. (2015). Integrating knowledge: Challenges raised by the ‘inventory of synthesis.’ Futures, 65(1), 123-135.

Dincã, I. (2011). Stages in the configuration of the transdisciplinary project of Basarab Nicolescu. In B. Nicolescu (Ed.), Transdisciplinary studies: Science, spirituality and society (No. 2) (pp. 119-136). Bucharest, Romania: Curtea Veche Publishing House. Retrieved from http://basarab-nicolescu.fr/Docs_Notice/Irina_Dinca.pdf

Dohn, N. B. (2010). The formality of learning science in everyday life: A conceptual literature review. NorDiNa, 6(2), 144-154.

Du Plessis, H., Sehume, J., & Martin, L. (2013). The concept and application of trandisciplinarity in intellectual discourse and research. Johannesburg, South Africa: Real African Publishers.

Findley, T. W. (1989). Research in physical medicine and rehabilitation II: The conceptual review of the literature and how to read more articles than you ever wanted to see in your entire life. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 68(2), 97-102.

Godemann, J. (2011). Sustainable communication as an inter-and transdisciplinarity discipline. In J. Godemann & G. Michelesen (Eds.), Sustainablity communication (pp. 39-54). London, England: Springer.

Hartling, L. M., Linder, E. G., Britton, M., & Spalthoff, U. (2013). Beyond humiliation: Toward learning that dignifies the lives of all people. In G. P. Hampson & M. Rich-Tolsma (Eds.), Leading transformative higher education (pp. 134-146). Olomouc, Czechia: PalackÍ University Press.

Hirsch Hadorn, G., Hoffmann-Riem, H., Biber-Klemm, S., Grossenbacher-Mansuy, W., Joye, D., Pohl, C., Wiesmann, U., & E. Zemp, E. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of transdisciplinary research. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Jagues, D., & Salmon, G. (2007). Learning in groups. Abington, England: Taylor & Francis.

Jesson, J., Matheson, L., & Lacey, F. M. (2011). Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques. London, England: Sage.

Kennedy, M. (2007). Defining a literature. Educational Researcher, 36(3), 139–147.

Kläy, A., Zimmermann, A. B., & Schneider, F. (2015). Rethinking science for sustainable development: Reflexive interaction for a paradigm of transformation. Futures, 65(1), 72-85.

Klein, J. T. (2008). Evaluation of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 35(2S), S116-S123.

Klein, J. T., Grossenbacher-Mansuy, W., Häberli, R., Bill, A., Scholz, R., & Welti, M. (Eds.). (2001). Transdisciplinarity: Joint problem solving among science, technology, and society. Berlin, Germany: Birkhäuser Verlag.

Lawrence, R. J. (2015). Advances in trandisciplinarity: Epistemologies, methodologies and processes. Futures, 65(1), 1-9.

Leavy, P. (2011). Essentials of transdisciplinary research. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Lozano, R. (2014). Creativity and organizational learning as a means to foster sustainability. Sustainable Development, 22(3), 205-216.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2009). Integral leadership’s potential to position poverty within transdisciplinarity. Integral Leadership Review, 9(2). Retrieved from https://transdisciplinaryleadership.org/4758-feature-article-integral-leadership%E2%80%99s-potential-to-position-poverty-within-transdisciplinarity1

McGregor, S. L. T. (2012). Complexity economics, wicked problems and consumer education. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 36(1), 61-69.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2015). The Nicolescuian and Zurich approaches to transdisciplinarity. Integral Leadership Review, 15(3) https://transdisciplinaryleadership.org/13135-616-the-nicolescuian-and-zurich-approaches-to-transdisciplinarity/

McMillan, H. S., Morris, M. L., & Atchley, E. K. (2011). Constructs of the work/life interface: A synthesis of the literature and introduction of the concept of work/life harmony. Human Resource Development Review, 10(1), 6-25.

Newig, J. (2007). Does public participation in environmental decisions lead to improved environmental quality?: Towards an analytical framework. Communication, Cooperation, Participation, 1, 51-71.

Nicolescu, B. (2002). Manifesto of transdisciplinarity [Trans. K-C. Voss]. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Nicolescu, B. (2010). Disciplinary boundaries – What are they and how they can be transgressed? Paper prepared for the International Symposium on Research Across Boundaries. Luxembourg, University of Luxembourg. Retrieved from http://basarab-nicolescu.fr/Docs_articles/Disciplinary_Boundaries.htm

Nicolescu, B. (2011). Methodology of transdisciplinarity-Levels of reality, logic of the included middle and complexity. In A. Ertas (Ed.), Transdisciplinarity: Bridging science, social sciences, humanities and engineering (pp. 22-45). Austin, TX: TheAtlas Publishing.

Nicolescu, B. (2014). From modernity to cosmodernity. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Penker, M., & Muhar, A. (2015). What’s actually new about trandisciplinarity? How scholars from applied studies can benefit from cross-disciplinary learning processes on transdisciplinarity. In P. Gibbs (Ed.). Transdisciplinary professional learning and practice (pp.135-147). New York, NY: Springer.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2005): Systematic reviews in the social sciences. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Pohl, C., & Hirsch Hadorn, G. (2007). Principles of designing transdisciplinary research. Munich, Germany: OEKOM.

Pohl, C., & Hirsch Hadorn, G. (2008). Methodological challenges in transdisciplinary research. Natures Sciences Sociétés, 16(2), 111-121.

Polk, M. (2015). Transdisciplinary co-production: Designing and testing a transdisciplinary research framework for societal problem solving. Futures, 65(1), 110-122.

Popa, F., Guillermin, M., & Dedeurwaerdere, T. (2015). A pragmatist approach to

transdisciplinarity in sustainability research: From complex systems theory to reflexive science. Futures, 65(1), 45-56.

Proitz, T., Mausethagen, S., & Skedsmo, G. (2015, September). Data use in education: A conceptual literature review. Paper presented at the European Educational Research Association Conference. Retrieved from http://www.eera-ecer.de/ecer-programmes/conference/20/contribution/35405/

Rossini, F. A., & Porter, A. L. (1981). Interdisciplinary research: Performance and policy issues. Risk Analysis, 13(2), 8-24.

Schauppenlehner-Kloyber, E., & Penker, M. (2015). Managing group processes in transdisciplinary future studies: How to facilitate social learning and capacity building for self-organised action towards sustainable urban development? Futures, 65(1), 55-71.

Shrivastava, P., & Ivanaj, S. (2011). Transdisciplinary art, technology, and management for sustainable enterprise. Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering and Science, 2, 81-92.

Solway, R., Camic, P. M., Thomson, L. J., & Chatterjee, H. J. (2016): Material objects and psychological theory: A conceptual literature review. Arts & Health, 8(1), 82-101.

Songca, R. (2006). Transdisciplinarity: The dawn of an emerging approach to acquiring knowledge. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies, 1(2), 221-232.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, 26( 2), xiii-xxiii.

Wickson, F., Carew, A. L., & Russell, A. W. (2006). Transdisciplinary research: Characteristics, quandaries and quality. Futures, 38(9), 1046-1059.

Yeung, R. (2015). Transdisciplinary learning in professional practice. In P. Gibbs (Ed.). Transdisciplinary professional learning and practice (pp.89-96). New York, NY: Springer.