1/18 – Leadership Quotes including Lev Gordon, Vasily Nalimov, Vladimir Solovyov, Ken Wilber and Allan Combs

blank

Lev Gordon

“Giving words to one’s own stance, explicitly outlining and defining one’s position always, by default principles of our human universe, brings forth antagonistic counterreaction. Hidden, implicitly performed action, even if it is large-scale, attracts less attention: It softly enters the world and perpetuates itself as water soaking into fields, while ice stays on the surface. Hidden action uses the soft and powerful force of water-like influence, sometimes interchanging it with forceful and adamant activities.”

“Any person who reaches higher levels of self development and expands her boundaries to include, first, her own nation, then the entire humanity and planetary civilization, and, eventually, the entire trans-planetary universe starts to see and think in a much wider and deeper fashion, including ever-increasing spans and dimensions of space-time. Such a person starts to care not only about tomorrow, but also about forthcoming 5–25 years, and some exceptional individuals see the span of 100–1000 years. These individuals gain interior maturity which makes them capable to pursue strategic and civilizational goals (to make the planetary civilization significantly better, to help humanity’s progress, to actualize the potential of divine consciousness at a whole-humanity scale and so on). It is essential to foster such leadership.”

— Lev Gordon (Columbia Business School / Harvard Business School Alumni; Co-founder of Association for city development and Forum of Living Cities; Expert with Russian Parliament, National Agency for strategic initiatives and Civic Chamber of Russian Federation)

Vasily Nalimov

“A philosopher, first and foremost, is someone who has full command of the polyphony of philosophical thought. To criticize other philosophical systems means to fail to accept, or to fail to understand the language in which they are presented. After all, each type of language says exactly what can be said in it. Each type of language will sooner or later talk itself out and will be retired to the repositories of culture. Sometimes the old comes back to life. It comes back to life when what is said in an old language finds a new resonance in one of the new languages. This way, the continuity of philosophical thought is established. We constantly look back to the past, and we run ahead into the future. The past and the future are always present in the now.

Each philosophical language has its own basic system of notions, and correspondingly, its systems of concepts and arguments. Each language opens up the possibility to ask its own set of specific questions—questions that only pertain to this language. Using his or her own specific language, every philosopher illuminates only some aspects of being that happen to be important to him or her.”

— Vasily Nalimov; this fragment transl. from Russian by Joachim Faust and Eugene Pustoshkin (an excerpt from V. V. Nalimov’s book Spontaneity of Consciousness, Moscow: Vodoley Publishers, 2007. P. 22-23)

“Perhaps the culture of the continuous vision of the world will become “the culture of not-doing,” where preference will be given to spontaneous development, and not to the unreserved and destructive activities in the name of a goal to which we are ascribing an unconditional value. But can we possibly imagine such a culture of “not-doing”? Some knowledge has come to us from the Oriental outlook. Something is written in the Gospels: the parable of the birds in the air who neither sow nor reap. We have also read something to the point in the teachings of the Mexican sorcerer Don Juan recorded by Castaneda (1972). Still, what is “not-doing”? It must not be confused with idleness. The culture of not-doing is actually that of “soft” doing. The slogan “Knowledge is power” proclaimed by Francis Bacon needs a more profound interpretation. The power of knowledge should not be suicidal. We have by now accumulated sufficient experience showing that rigid non-probabilistic knowledge generates blind and stupid force. Action in the probabilistic world does not signify a stubborn violation of the world but a collectively comprehended risk that presupposes ways of retreat or changes from the course originally outlined. This is the only way to act when we attempt to change nature. Contemporary technology tempts us to invent and realize grandiose projects. However, ecological forecasts, if possible at all, can only be made in a soft, probabilistic form. Is it not safer to act more cautiously, by introducing into the projects beforehand ways of retreat? Perhaps, this is also true of social activities in their broad meaning. Is such a culture of soft doing possible at all? Only the progress of the continuous vision of the world will bring us closer to the answer.”

— Vasily Nalimov (Realms of the Unconscious: The Enchanted Frontier. — Philadelphia, PA: ISI Press, 1982; free PDF is downloadable at Dr. Eugene Garfield’s website.)

Vasily Vasilyevich Nalimov (1910–1997) was a Russian philosopher and humanist and wrote on transpersonal psychology. His main areas of research were the philosophy of probability and its biological, mathematical, and linguistic manifestations. He also studied the roles of gnosticism and mysticism in science. Thompson (1993) summarizes Nalimov as: “…philosopher, educator, devoted husband, mathematician, dissident, writer, and (although he may deny it) visionary.”

See an ILR article about Vasily Nalimov: Svetlana Maltseva, “A Man Who Surpassed His Time” (2013)

“Gebser comments that “creativity is of the Origin,” (1949/1986, p. 313), and Feuerstein (1990) notes that the prefix sahaja in the term sahaja-samadhi means “spontaneous,” indicative of the idea “that freedom is not external to us but our very condition” (p. 297). In the same vein, the Russian philosopher and semanticist V.V. Nalimov (1990) believes that spontaneity touches the deepest transpersonal mystery of human existence.

All the above descriptions are simply elaborate ways of saying that realized consciousness is deeply and wholly alive in the moment. In its intense presence, it discovers a world steeped in freshness and mystery, yet paradoxically “ordinary.” Guenther speaks of “the immediacy of [the world’s] abiding thereness” (1989; p. 230) and Gebser of “the itself.” My own preference is for the Zen characterization of a world arising each moment in its own “suchness.”

— Allan Combs, “The Evolution of Consciousness: A Theory of Historical and Personal Transformation” (1993, p. 60)

(Combs A. The evolution of consciousness: A theory of historical and personal transformation // World Futures. — 1993. V. 38. No. 1–3. Pp. 43–62.)

Ken Wilber on Russia

“Russia actually has a history of Integral thinking, and certain of its tenets run deep in Russian blood. There is, for example, the rather extraordinary Vladimir Solovyov (1853–1900), who introduced what he called an ‘integral’ form of knowledge, and made it the basis of discovering the unity between the human and the Divine. His lectures on ‘The Divine Humanity’ in 1878 were a milestone in Russian history, and were attended by many young Russian intellectuals of the time, including Dostoevsky and Tolstoy (Solovyov is thought to be the prototype of both Alyosha and Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov). Solovyov’s followers, such as S. L. Frank and Sergei Bulgakov, furthered early Integral thinking. Deeply embedded in the movement is a desire to understand and experience what Frank called ‘all-unity’ or ‘total unity’—to leave nothing out, to include all. Solovyov particularly saw this as the role of divine Sophia, or Wisdom.

And it is divine Wisdom, by whatever name, that continues to empower Integral movements the world over. The desire is to cease fragmenting the world, stop tearing it into shreds, ripping it into shards, devastating its totality and reducing it to slices and slips, broken tokens and partial silos. For one thing is certain: of all the really wicked problems facing humanity at large in today’s world, none of them can be solved with piecemeal, fragmented, partial approaches. Our approach is, and must increasingly become, Integral—whole and inclusive, systemic and comprehensive, compelling and embracing.

Russia is coming out of some 70 years of communism, and is faced now with building a culture that, in many ways, picks up at orange Reason, reconstructs a healthy and functioning democratic government, overcomes its broken middle class and widespread organized crime, and enters the world stream of commerce and communication free of distortion, domination, and coercion. And this is introducing a greater measure of Freedom not only to society as a whole, but to each and every individual in the culture.”

— Ken Wilber, an Integral philosopher who founded the meta-field of Integral Theory and Practice (from the welcoming letter to the emerging Russian Integral Movement, December 2012)

Left to Right: Karolina Gruszka (actress), Cazimir Liske (actor), Ken Wilber (Integral philosopher), Alexander Nariniani (Integral publisher), Ivan Vyrypaev (playwright)—during a visit to Ken Wilber’s Loft in August 2013

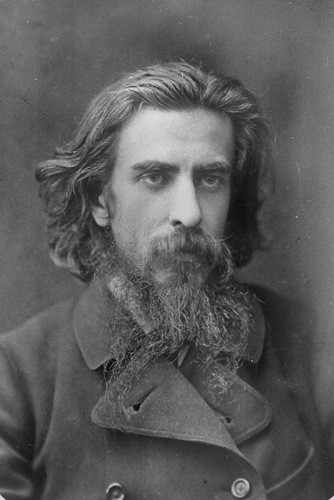

Vladimir Solovyov

“Dostoevsky not only preached, but, to a certain degree also demonstrated in his own activity this reunification of concerns common to humanity—at least of the highest among these concerns—in one Christian idea. Being a religious person, he was at the same time a free thinker and a powerful artist. These three aspects, these three higher concerns were not differentiated in him and did not exclude one another, but entered indivisibly into all his activity. In his convictions he never separated truth from good and beauty; in his artistic creativity he never placed beauty apart from the good and the true. And he was right, because these three live only in their unity. The good, taken separately from truth and beauty, is only an indistinct feeling, a powerless upwelling; truth taken abstractly is an empty word; and beauty without truth and the good is an idol. For Dostoevsky, these were three inseparable forms of one absolute Idea. The infinity of the human soul—having been revealed in Christ and capable of fitting into itself all the boundlessness of divinity—is at one and the same time both the greatest good, the highest truth, and the most perfect beauty. Truth is good, perceived by the human mind; beauty is the same good and the same truth, corporeally embodied in solid living form. And its full embodiment—the end, the goal, and the perfection—already exists in everything, and this is why Dostoevsky said that beauty will save the world.”

— Vladimir Solovyov (1853–1900), a Russian philosopher, theologian, poet, pamphleteer and literary critic, who played a significant role in the development of Russian philosophy and poetry at the end of the 19th century and in the spiritual renaissance of the early 20th century. (Vladimir Soloviev, The Heart of Reality, trans V. Wozniuk, p. 16.)

“True philosophy, philosophy as it properly should be, is impossible without positive science and theology, just as the genuine forms of the latter two are impossible without the others. In integral knowledge, science, philosophy and theology have the same content but merely approach that content differently; it is of no consequence from which stage one begins the journey to integral knowledge. For this reason, Solov’ëv believes we can designate integral knowledge equally well as integral philosophy, integral science or integral theology, each choice merely serving to emphasize the respective starting point. For this reason, we can presume that Solov’ëv’s explicit decision to examine integral knowledge as a philosophical system, and not as a science or a theological system, is purely arbitrary. Having made that choice, though, we see that the term “philosophy” has many different, even opposed, meanings, chief among them being: (1) Philosophy is merely a theoretical, i.e., academic, discipline; and (2) philosophy is primarily a practical concern. In the first sense, philosophy is concerned exclusively with theoretical questions having to do with the human cognitive faculties, whereas in the second sense it is concerned additionally with the higher human aspirations and ideals. (Pp. 77–78)

Recognizing deficiencies in empiricism and rationalism as mutually exclusive philosophical directions and approaches, [Solov’ëv] offered mysticism as the necessary missing ingredient without spelling out just how it dispels those weaknesses” (P. 65).

— Thomas Nemeth on Vladimir Solovyov’s philosophical system of integral knowledge (Nemeth, T. The Early Solov’ëv and His Quest for Metaphysics. Springer, 2014.)