Jorge Taborga

Abstract

This case study investigates the impact of leadership stage development in transformational change initiatives. In particular, it looks at how the structure and characteristics of leadership teams determine large change outcomes in organizations. The core theory that grounds this research is that post-conventional leadership is required for organizational transformation to take place. This theory comes from the work of Bill Torbert and his colleagues. Along with this theory, the researcher explores a change leadership team structure (holarchy) and characteristics associated with a holistic team organized along the integral dimensions of interior-exterior and individual-collective. Integral models are leveraged to convey the developmental nature of leadership teams and their effect on transformational change. Two questions are pursued in this research: a) how leadership stage development correlates to the success of transformational change initiatives, and b) how the make-up of a change leadership team affects outcome in the absence of leadership stage development awareness. This research follows a comparative case study research methodology. Senior leaders of an organization that has undergone at least two large transformations in the last 5 years provided the details for this research.

Introduction

Purpose

The purpose of this case study research is to determine how post-conventional leadership as defined by Rooke and Torbert (1998) affects the outcome of large transformational change in organizations. In particular, this research aims to link post-conventional leadership with the way organizations structure their leadership teams for large change initiatives and the results they achieve.

Background

Since the time that large transformational changes in organizations became the subject of research in the fields of management and leadership studies, it appears that only one in three change initiatives has been deemed successful (Meaney & Pung, 2008). Social scientists, psychologists and organizational developers have amassed thousands of volumes about change management and the role of leadership in change initiatives (Vinson & Pung, 2006). However, this large body of resources has not altered the success ratio in transformational change since statistics started to appear in the nineties. Aiken and Keller (2009) state “it seems that, despite prolific output, the field of change management hasn’t led to more successful change programs” (p. 1).

Isern and Pung (2007) characterize large organizational transformation as having “startlingly high ambitions, the integration of different types of change, and a prolonged effort often lasting many months, in some cases, even years (p. 1)”. Kotter (2006) and other change luminaries have provided complete methods for managing large change, often claiming that their method would at least raise the probability of success. Aiken and Keller from McKinsey in their article The Irrational Side of Change Management (2009) offer four basic conditions for large transformation to take place in an organization: a) a compelling story, b) role modeling, c) reinforcing mechanisms, and d) capability building.

Torbert and Associates (2004) approach the subject of organizational transformation purely from the leadership standpoint irrespective of method and practice. Their premise is based on research they conducted which yielded a seven stage developmental framework for leaders. Rooke and Torbert (2005) state that leaders evolve to one of seven stages of leadership where they will most likely stay for the better portion of their lives with a few continuing to slowly evolve into higher levels. This evolution is guided by the experiences of the individual, which start early in life (Simcox, 2005).

Torbert and Associates (2004) posit that only in the last three of the seven stages of leadership development do individuals have enough reflective meaning-making to successfully drive transformational change. These authors argue that a high level of internal awareness is necessary for a leader to grasp all of the nuances present in large change situations. Torbert defines these later stage leaders as transformative learners, that is, they are in a constant path of self-development. This notion of transformative leaders as being self-transforming is well addressed in the literature of leadership studies (Nailon, Delahaye & Brownlee, 2007). However, Torbert and his associates are more deliberate in their pronouncement and associate certain leadership developmental stages with a capability that presumably could have profound impact in the success of large transformational initiatives.

Rationale

The subject of transformational change is not new and, as stated earlier, the results have not improved even with the ever-increasing amount of materials available on the subject. As documented in the IBM study (Capitalizing on complexity, 2010), the priority for most organizational leaders is dealing with complexity driven by the structures of globalization, world economies, shifts in consumer power, environmental concerns and the need for organizations to address the evolving requirements of their social systems. This complexity seems to present even larger challenges to the mostly unsuccessful transformational initiatives.

Torbert’s leadership stage development framework appears promising in explaining why only a third of the large change projects succeed. From his research, the author posits that only 15% of the leader population has the capability to execute transformational change (Rooke & Torbert, 2005). Given that most organizations and leaders are not familiar with Torbert’s work, it stands to reason that their transformational initiatives are not consciously staffed to include one or more of these latter stage leaders. Consequently, transformational projects will have a random chance of success based on their leader membership.

Assuming that the research of Torbert and his associates is correct and that leadership stage development is a key determinant of the success of transformational change in an organization, then conscious assignment of leaders based on their developmental stages is paramount. This is most fundamental relative to transformational leaders but it also applies to the inclusion of the other stages of leadership development. According to Burke (2011), most change project teams are assembled based on roles, organizational politics and on who is available. To make matters worse, we are clueless on the leaders’ developmental stages and on the unintended consequences of their assignment. This research correlates the outcome of organizational transformation initiatives to the make-up of change leadership teams.

Research Questions

Two questions orient this research: a) how leadership stage development correlates to the success of transformational change initiatives, and b) how the make-up of a change leadership team affects outcome in the absence of leadership stage development awareness.

Research of the Literature

Four topics are explored in the literature research for this study: a) integral transformational change, b) leadership stage development, c) transformational change and transformative learning, and d) the holistic leadership development model.

Integral Transformational Change

The concept of the holon was introduced in 1967 by Arthur Koesler in his book The Ghost in the Machine (Koestler, 1990). A holon is both a part and a whole. Koesler aimed to bridge the dichotomy of philosophical holism and scientific reductionism through a structure that could express both (Edwards, 2005). Social scientists have since used holons to describe organizational structures. They are recursive in nature and share properties across levels.

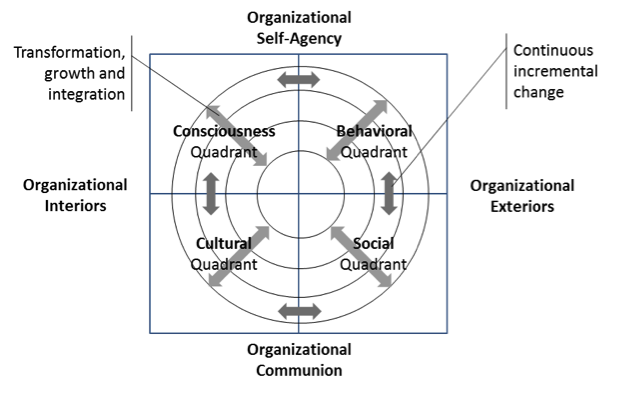

Ken Wilber, the philosopher behind the Integral movement, introduced the AQAL (All-Quadrants, All-Levels and All-Lines) framework to articulate the “fundamental domains in which change and development occur” (Edwards, 2005, p. 272). Wilber’s integral theory proposes that social phenomena require the consideration of at least two dimensions of existence: 1) interior-exterior, and 2) individual-collective (Wilber, 2000; Cacioppe & Edwards, 2005a, 2005b; Edwards, 2009). The interior-exterior dimension corresponds to the subjective/reflective experience in relationship to the objective or behavior-based reality. In the second dimension, the individual-collective refers to the relationship of the experience of self-agency and that of community. The AQAL framework is represented as a 2×2 matrix demarcated by these two dimensions. Figure 1 shows this framework.

Figure 1: This version of the AQAL framework was adapted from Edwards (2005) and Cacioppe and Edwards (2005a).

In the framework shown in Figure 1, the consciousness quadrant corresponds to the overall level of awareness in the organization. Pruzan (2001) explores the subject of organizations having consciousness attributes similar to individuals such as “being reflective, purposeful and values oriented” (p. 276). Pandey and Gupta (2007) define consciousness as the way organizations make meaning and relate to the world. In their view, organizations manifest their consciousness in three distinct manners: market (wealth creation), social responsibility, and spiritual (collective evolution and existential harmony).

The cultural quadrant of the organizational holon represents the values and beliefs and the underlying assumptions in an organization. This is in line with Schein’s definition of organizational culture as a pattern of shared basic assumptions, values and believes, and artifacts that the group developed as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration (Schein, 2010). The behavioral quadrant embodies the collection of emotions, cognitive processing, and all manifested actions. Organizational learning is a key part of this quadrant (Edwards, 2005). The last quadrant in the organizational holon corresponds to the social. Policies, procedures, processes, structures, systems, technologies and social norms are all manifestations of the social quadrant (Cacioppe & Edwards, 2005a).

Wilber defined developmental structures in the AQAL framework (Wilber, 2000). Two of these structures are relevant to organizations: developmental lines and levels. Figure 1 shows horizontal and vertical arrows that symbolize the continuous and incremental change that organizations go through. Wilber called these dynamic developmental lines, which in an organization may include “culture, goals, customer and community relations, ethics, corporate morals, marketing, governance and leadership (Cacioppe & Edwards, 2005b). Incremental changes typically occur from the co-evolution of the quadrants (Edwards, 2005).

The other dynamic structure in AQAL is the developmental levels depicted as diagonal arrows in Figure 1. They correspond to the stages of development that individuals and organizations go through as they are exposed to life experiences. Several researchers have conceptualized developmental frameworks including Piaget, Loevinger, Cook-Greuter, Graves, Kegan, Kohlberg, Wilber and Torbert (Lichtenstein, 1997). Moving from one level of development to the next requires large transformational changes as a result of a significant experience and a process of reflection and inquiry.

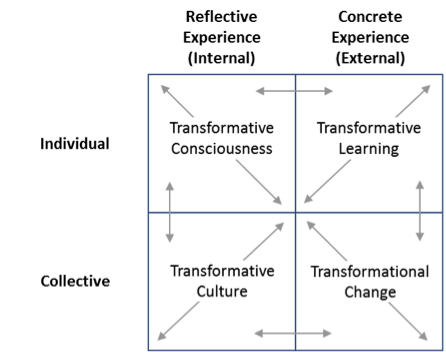

Expanding on the subject of a transformational change, a holon can be built that takes into account the dynamics of large change inside an organization. Figure 2 shows this holon. The consciousness quadrant takes on the specific dimension of transformative consciousness. Pandey and Gupta (2007) state that at the highest levels of consciousness “the organization is able to unleash the human power of introspection and reflexivity and show the capability to renew, adapt and transform itself” (p. 894). Transformative culture is the other internal quadrant in this holon. It reflects the cultural values associated with change. Sarros, Cooper and Santora (2008) state “the type of leadership required to change culture is transformational because culture change needs enormous energy and commitment to achieve outcomes” (p. 148).

Figure 2. The transformational change holon. The individual quadrants in this figure correspond to the developmental lines (changes) and levels (transformations) in an organization.

Along the external dimension of the transformational change holon we have the transformative learning quadrant. Mezirow (2000), Henderson (2002), and Gambrell, Matkin and Burbach (2011) view transformative learning as a fundamental behavior or practice inside an organization to achieve large changes. Peter Senge (1990) and the learning organization movement characterize the internal conditions for change as directly connected to the organization’s ability to learn. Henderson (2002) states “transformative learning is the process of examining, questioning, validating, and revising our perceptions of the world” (p. 200).

The last quadrant in the transformational change holon corresponds to the change systems present in an organization (Cacioppe & Edwards, 2005a). These systems support incremental and large transformational change (lines and levels of development). Leader development is an example of a transformational system that could have far reaching implications in transformation. However, most leadership development programs focus on behavior and skills and not transformational-type learning (Gambrell, Matkin & Burbach, 2011).

Leadership Stage Development

In 2007, Accenture conducted a worldwide survey of 900 top executives across large organizations to determine their effectiveness in developing top leaders that could handle rapid changes and be adaptable. Harung, Travis, Blank, and Heaton (2009) communicate the results from this survey showing a mere 55% success rate in developing top leaders. These results indicate that we are still looking for how to develop leaders and leadership in organizations.

There are many leadership frameworks in existence, most aiming to point out what good leaders do and how leaders should perform in certain situations (Harung, Travis, Blank, & Heaton, 2009). William Torbert introduced the concept of action-logic as a way to describe stages of development for leaders. Along with other stage development theorists such as Piaget, Loevinger, Cook-Greuter, Graves, Kegan, Kohlberg, and Wilber, Torbert formulated that leaders progress through successive stages of development “involving greater levels of complexity, responsibility, empathy, understanding of the world, and appreciation of the undefined creative potential of each moment” (Lichtenstein, 1997, p. 400).

During the eighties, Torbert and his colleagues conducted a multi-year study with the leaders of ten companies (Rooke & Torbert, 1998). In this research the activities of multiple levels of leadership were observed and also validated through the ego development test initiated by Jane Loevinger and further refined by Cook-Greuter that utilizes the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (SCT). Through their observations and testing, Torbert and his colleagues established a seven stage leader development framework. Each stage is comprised of specific action-logics or mindsets. In the framework, leaders developed from stage one and gradually move to a stage where they will operate for most of their lives (Simcox, 2005). Like other stage development frameworks, Torbert’s leadership stages capture the elements of complexity and meaning-making that leaders experience in the context of their roles. Table 1 summarizes the seven action-logics present in this framework.

Table 1. This table summarizes the seven action-logics in Torbert’s leadership development stages. It is an adaptation of Torbert and Associates (2004), and Rooke and Torbert (2005). The column with the “percent profiling at action-logic” comes from 495 leaders tested with the Leadership Development Profile (LDP) (Barker & Torbert, 2011).

|

Action Logic |

Characteristics |

Strengths |

% profiling at action logic |

| Opportunist | Win any way possible; self-oriented; manipulative; “might makes right” | Emergencies and competitive opportunities |

5% |

| Diplomat | Need to belong; avoid overt conflict; follow group norms; | Routine work; enforce standards; help bring people together |

12% |

| Expert | Logic and expertise; seek rational efficiency; be unique; perfectionist | Problem solving; design; improving efficiencies; contingencies; developing work products |

38% |

| Achiever | Long term goals; effective delegation; balance managerial duties and external demands; handle feedback | Day-to-day improvements; general team leadership and management; action and goal achievement |

30% |

| Individualist | Relativistic perspective; aware of emotions and self-expressions; non-judgmental; maverick; against norms | Independent creative work; consulting; drive change |

10% |

| Strategist | Value action inquiry, mutuality and autonomy; interweave short with long term; aware of paradox; creative conflict resolution; | Handle multiple roles; planning; future design; transformational change |

4% |

| Alchemist | Integrate material, spiritual, and societal transformation | Lead society-wide transformations |

1% |

According to Torbert and Taylor (2008), leadership development starts early in our lives as we navigate through the action-logics from the Opportunist level to the one in which we feel most comfortable. This will be the stage where we experience our “most complex meaning-making systems, perspective, or mental model we have mastered” (Simcox, 2005, p. 4). The seven action logics are divided into conventional and post-conventional. The first four stages (Opportunist, Diplomat, Expert and Achiever) correspond to the conventional action-logics. The majority of leaders (85%) operate from one of these conventional stages (Rooke & Torbert, 2005). Conventional leaders are focused on objective reality and their leadership actions are aimed at execution with minimal reflection, and modification of only behaviors and not action-logics themselves. In contrast, the post-conventional leaders are more likely to reframe problems and constraints and to recognize different action-logics in others (Torbert & Associates, 2004). Their aim is to create shared visions founded in diversity. Collaborative inquire is a hallmark of post-conventional action-logics which is used to develop solutions (Rooke & Torbert, 2005). These later-stage leaders can identify incongruities in their own thinking and experience and modify them to serve the global good.

In their research, Torbert and his colleagues found that post-conventional leaders are the ones capable of leading transformational change in organizations. These researchers did not find evidence of transformational capabilities in conventional leaders (Torbert & Associates, 2004). One of the key differences between conventional and post-conventional action-logics is single, double and triple loop awareness. Torbert & Associates (2004) state that conventional action-logic leaders have demonstrated single loop awareness only. With this type of awareness, only behaviors and operational facts can be assessed and modified. Double loop awareness is needed to reflect on goals, strategies and structures. In this context, structure refers to the action-logics themselves. Starting with the Individualist stage, Torbert and his colleagues observed double loop awareness relating it with the ability to transform an organization (Simcox, 2005). Triple loop awareness, which is associated mostly with the Alchemist level, brings reflection at the attention and intention levels along with vision.

In the conceptualization of leadership stage development, Torbert and his colleagues state, “[L]ater stages are reached only through journeying through the earlier stages” (Simcox, 2005, p. 4). Once a stage has been integrated by a leader, it remains part of his or her capabilities even when new stages are reached. The expectation is that leaders operate through various action-logics depending on the situation. A leader may behave as a “Diplomat” in one setting and as an “Individualist” in another based on what is required. As with any stage development framework, there is always the risk of believing that a later stage is better than an earlier one. Organizations need leaders in all stages of development to be successful (Rooke & Torbert, 2005). Further, competence is not an attribute of a developmental stage.

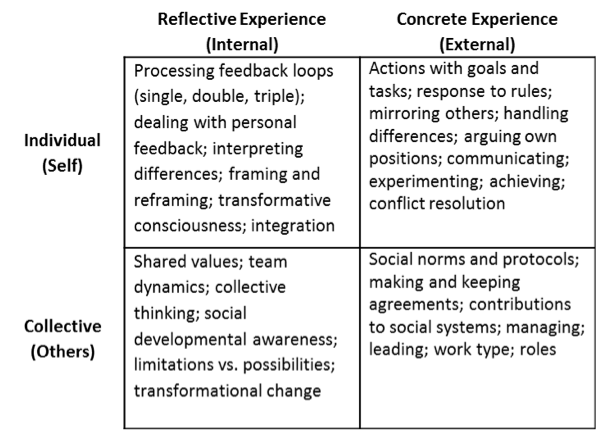

Torbert and his colleagues found that leaders can develop across action-logics. This is primarily true in the first conventional stages (Torbert & Associates, 2004). Common leadership development programs in organizations are geared to develop leaders with Expert action-logics into Achievers. Most organizations do not have awareness of what it takes to develop an Achiever into an Individualist (Rooke & Torbert, 2005). Consequently, most post-conventional leaders are formed through experiences external to the workplace and bring their higher action-logics to their organizations after they have already formed (Simcox, 2005). Figure 3 provides an integral model that captures the elements of Torbert’s leadership stage development framework. The internal dimension shows the reflective aspects of leadership both at individual and collective levels. The external dimension does the same with the objective world of a leader.

Rooke & Torbert (2005) state that the leadership stage development framework applies to organizations acting at a collective action-logic. They posit that the most effective organizations would act at the Strategist level where learning and growth opportunities would be the norm for individuals and the collective. However, these researchers found that most organizations operate at the Expert or Achiever action-logics. The reason for this is that organizations prefer unambiguous targets and deadlines, working with specific strategies and tactics (Rooke & Tolbert, 2005).

Figure 3. This figure is a synthesis of the characteristics of the seven action-logics from Simcox (2005), Torbert and Associates (2005), and Rooke and Torbert (2005).

Transformational Change and Transformative Learning

Based on the attributes of the seven leadership stages from Torbert and his colleagues only leaders in the post-conventional action-logics understand and can navigate through transformational change. If this premise is correct, how do these leaders guide change where the frame of reference for all individuals in an organization must change for a successful transformation? Transformational change for an organization implies individual transformational change for its members, which further implies that the leaders must change first—in this case the post-conventional leaders whom are capable of this type of change. These implications point to two types of changes during a transformation: organizational and individual. Although organizational change theory addresses the change of individuals as an end state, most of this theory does not address it as part of the change itself (Henderson, 2002). This leaves a gap for organizations and leaders attempting large change through the limited scope of conventional change management practices.

Adult development theories have led to the formation of Transformative Learning (TL), which is “the process of examining, questioning, validating, and revising our perceptions of the world” (Henderson, 2002, p. 200). TL is about individual change and how we see ourselves and make meaning of the world around us. Based on this definition, post-conventional leaders are transformative learners. This is supported by the literature on transformational leadership (Kegan, 2000; Mezirow, 2000; Mezirow & Taylor, 2009). According to Mezirow (1991), considered the founder of TL, transformative learners distinguish between three types of reflection: a) content, b) process, and c) premise. Process reflection involves checking on the problem-solving strategies while premise reflection questions the problem itself. Both of these correspond to double-loop feedback awareness, the hallmark of post-conventional action-logics.

Henderson’s article Transformative Learning as a Condition for Transformational Change in Organizations (2002) provides a comprehensive analysis of organizational change and Transformative Learning theories. This author maps attributes of each theory to the transformation of an organization and the individual. Henderson’s conclusion is that all the major theories of organizational change consider individual change as an end but not as the means. In contrast, all of the theories of transformative learning consider individual change as the means. This important distinction establishes the connection with post-conventional action logics where “internal” change is the pre-requisite for transformational change (Rooke & Torbert 1998, 2005; Torbert & Taylor, 2008; Barker & Torbert, 2011). Nailon, Delahaye and Brownlee (2007) distinguish between transactional and transformational leaders. These authors posit that transformational leaders are concerned about efficiencies and organizational goals with a focus on supporting their staff emotionally and intellectually. In contrast, transactional (conventional action-logic) leaders accentuate inefficiencies and provide negative feedback.

Holistic Transformational Team Model

To gain a deeper understanding of the structure of a change leadership team, we return to Koestler and the concept of the holon. According to Koestler (1990), holons, because of their dual nature (part and whole), are necessarily connected to other holons in a vertical structure he called holarchy, which can be viewed as a multi-layer system. It is important to note that holarchies do not form larger holons but simply arrange them to represent conceptual entities. Koestler (1990) conceived that holarchies structure social organizations into what he called open hierarchical systems capable of learning and evolving.

Edward’s views in alignment with Koestler’s stipulate that organizations evolve along the lines and levels of development as a holarchy (Edwards, 2005; Cacioppe & Edwards, 2005b; Edwards 2009). Rooke and Torbert (2005) in Seven Transformations of Leadership make the point that organizations have a collective leadership developmental stage. Applying the holonic structure to this concept, we arrive at a holarchy that has the internal-external and individual-collective dimensions capable of transformation present in its members. The questions that emerge are how holons look at each leadership stage and how organizations can apply change holarchy principles.

Earlier in this document, a conceptual holon for Torbert’s leadership stage development was presented (Figure 3). The contents of this holon correspond to integral attributes that relate to the seven levels of the leadership stages. Even though this model is descriptive, it provides a fundamental structure in which to build the dimensions of a holistic leadership team holon. Cacioppe and Edwards (2005b) postulate that a holistic model must not only contain the dimensions on internal-external and individual-collective but it should clearly articulate the lines and levels of development along these dimensions.

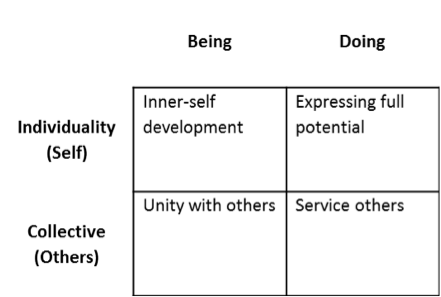

In her dissertation, Marjolein Lips-Wiersma (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2011) introduced the concept of the Map of Meaning which is a 2 x 2 structure which provides a possible holistic framework to capture the elements of a transformational team holarchy. Lips-Wiersma and Morris (2011) define four developmental containers along the two integral dimensions of internal-external and individual-collective. These containers are: 1) developing the inner-self, 2) unity with others, 3) expressing full potential, and 4) service others. The authors performed an extensive validation of their framework at a variety of organizations and with individuals at different levels of leadership. Their approach was to measure the level of meaningfulness, including personal development associated with the integral expression of all four quadrants by their subjects. In their findings, a person with a strong sense of inner self-development, connection with others, finding realization in their activities, and having a strong sense of service would experience the highest level of meaningfulness. It is this author’s view that these four states of meaningfulness correspond to Torbert’s post-conventional attributes of the post-convention levels of leadership: the Individualist, Strategist and Alchemist.

Lips-Wiersma and Morris (2011), describe their model as having four pathways held in tension along each dimension of the quadrant. One pathway counters the needs of self with the needs of others while the other tugs between being (reflection) and doing (action). These pathways are congruent with the integral dimensions of internal-external (being and doing) and individual collective (self and others). Figure 4 shows the resulting holon from the Map of Meaning (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2011).

Figure 4. Map of Meaning holon. This is an adaptation from the Map of Meaning described in Lips-Wiersma and Morris (2011). These authors do not use Wilber’s AQAL format but the representation of their map can easily be adapted to this quadrant structure.

In Figure 4, inner self-development results from the meaningfulness that comes from active involvement with the person we are becoming as a result of being engaged in our life and work—from being a good person to being the best we can possibly be. The unity with others quadrant refers to the meaningfulness of living together with other human beings. This does not mean uniformity. It primarily involves finding unity in diversity. Expressing full potential refers to the meaningfulness of making our mark in the universe. It is active and outwardly focused. This quadrant is based on the concept that we are all unique, and that we are responsible for bringing our unique gifts and talents into the world. The service to others quadrant is about the human need to make contributions to the wellbeing of others, from helping an individual to making a difference in the wider world.

Applying the Map of Meaning holon to Torbert’s seven leadership stages, we end up with seven holons, which can form a holarchy for the transformational change team. Figure 5 shows a representation of this holarchy. The shading of the quadrants in this figure represents the level of focus for each of the leadership stages. Focus in this context means a high degree of awareness of the leader in the particular quadrant. There are two degrees of focus being represented, primary and secondary. Primary focus provides the driving force for the actions of the leader while the secondary focus complements them. For instance, the Achiever has a strong focus on the application of leadership in the service of others and a secondary focus on expressing full potential. The strategist is focused in all of the quadrants except for unity with others. Non-shaded quadrants do not necessarily mean absence of activity in that location of the holon. It simply means not enough activity to be consequential in the current meaning-making of the individual as a leader. As an example, the Diplomat appears to be totally focused in the service to others quadrant. This individual will engage with others and to some degree work to express full potential. However, based on Rooke & Torbert (2005), the Diplomat as a leader seeks to maintain the status quo, which corresponds to being in almost blind service to the other leaders and the organization with whom this type of leader is engaged.

Given the Map of Meaning holon and the direction provided by Cacioppe and Edwards (2005b) on an integral leadership stage model, a holistic transformational team holon can be specified. The objective of this specification is to have a blueprint for the leaders in a transformational team so that membership can be made consciously and not randomly. The goal in building a transformational team should conceptually be a holarchy in which the individual holons bring the right and complete focus for it to be transformational. In essence, the transformational holarchy should have complete focus in each quadrant provided by one or more of its holons. There should not be any quadrants with an absence of focus.

Case Study

Case Study Subject

Medcab (not its real name), a public medical devices company that was the subject of the case study, is headquartered in the San Francisco Bay Area. This is a medium size company that experienced rapid growth over the last ten years. This precipitated the need for transformation both in its products and services, and also in its internal processes. The company is primarily focused on the US market and has a distributed workforce with about a thousand employees. Company yearly revenues are around $330 million.

Transformational Change Initiatives

Medcab has had a few transformational initiatives over the last five years. Among them are two which are the basis for the case study. Project 1 was a broad process reengineering initiative affecting the entire company from quoting products and services to closing the financial books. The change efforts for this project started in January of 2008 with the introduction of the first set of changes a year later. Two additional years were required to complete the transformation. Although the results of the overall transformation have been positive for the company, the initial results of Project 1 experienced during most of 2009 were challenging by all accounts. These results correlate to two thirds of all transformational processes that are challenged or fail (Meaney & Pung, 2008).

Project 2 encompassed the development, manufacturing and market availability of eleven new products that transformed the company’s product offering in record-setting time. This project launched in March of 2010 with the formation of project teams and the direction from the CEO to complete all products by the following May. Historically, Medcab had difficulty executing multiple products in parallel and the average time for each far exceeded the goal of launching all eleven products in that timeframe. New development processes and a different method of cross-functional collaboration were needed to accomplish the objectives, both requiring transformation. The outcome of Project 2 was exceptional with all eleven products being launched in May of 2011 with immediate availability. This transformational initiative falls in the one third of the population of successful change initiatives.

Participants and Their Qualifications

The case study sponsor was the Vice President of Human Resources at Medcab. She provided the background on the two selected initiatives and others that were considered. The criteria in appendix B were utilized to select the two case studies to compare and contrast via this case study. Five individuals were identified by the sponsor to participate in the interview process for the case study. They all met the criteria identified in appendix C. This researcher was most particular about the dual membership of the participants: a) they all had to be leaders in both change initiatives and b) be influential in their outcomes. The driver for these requirements was to ensure a common experience and perspective by the case study participants. Appendix D defines the current roles of the participants at Medcab and their roles in both projects

Project Holarchies

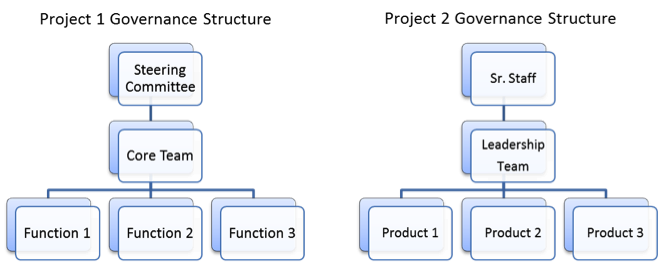

Figure 6 shows the governance structure for both projects. In this figure we can see that both initiatives had a three layer leadership structure. For Project 1 the first layer was composed of members of Medcab’s Senior Staff (executive vice presidents) and the functional vice presidents affected by the project’s changes. Their mission was that of oversight. The second governance layer for this project was the Core Team. It was composed of functional experts at senior manager and director levels with the mission of leading and managing the day-to-day activities of the change initiative. The interview findings observed that not all Medcab functions were represented in the Core Team and that its members had their own specific agendas.

In Project 1, the third layer was comprised of the leaders of each function affected by the initiative. These functional leaders were expected to drive the change for their function. However, there is little evidence that this actually took place. The case study participants indicated that the functional leaders in Project 1 (layer 3) relinquished this responsibility to individual contributors and more junior personnel. In addition, the third layer of Project 1’s governance holarchy did not feel responsible for the change, thus expecting the Core Team to drive the change details and perform the actual work.

In contrast to Project 1, the first governance layer of Project 2 was formed purely with members of Medcab’s executive team, Senior Staff. This governance layer acted coherently and provided the overall governance and direction for the program. The second layer of Project 2 did not exist until four months before the launch of the eleven new products. Each product team (the third layer) had its own core or management team and reported its progress directly to Senior Staff (first governance layer). As Project 2 proceeded and encountered the unknowns of the functional integration required by the massive product launch, Senior Staff decided to form the Leadership Team, the second layer of the governance structure for Project 2. This team was composed of vice presidents and directors of most functions in the company. The Leadership Team became responsible for the execution of the product launch across all functional disciplines (similar charter to Project 1’s Core Team).

The structure, mission and attitude of the third level in the governance structure for Project 2 were completely different from its counterpart. Instead of the teams at the third layer being composed of individual functions, the Project 2 teams at the third governance level were product oriented, encapsulating the required functional members for each product. The challenge of these teams was their uneven functional representation and the lack of know-how to coordinate a massive product launch.

Map of Meaning Analysis

From a Map of Meaning holon perspective, the participants provided their insight, which are compiled in appendix E. This appendix shows a summary of the responses from the interview questions arranged by each of the dimensions in the Map of Meaning: Inner Development, Unity with Others, Expressing Full Potential, and Service Others. Table 2 provides a rating for each dimension based on the feedback provided by the participants.

Table 2. Map of Meaning ratings. The ratings specify: 1 – no evidence of any development during the project; 2 – about 25 percent development; 3 – about 50 percent development; 4 – about 75 percent development; and 5 – full evidence of a developed dimension.

| Map of Meaning Dimension |

Rating for Project 1 |

Rating for Project 2 |

| Inner Development |

1 |

3 |

| Unity with Others |

2 |

4 |

| Expressing Full Potential |

3 |

4 |

| Service Others |

2 |

3 |

Table 2 indicates that participants in Project 1 did not experience any discernible personal growth. In this project, the Core Team and the individual functions could not form a coherent whole. Individuals kept to their agendas and their own ideas. Learning was limited to technical matters and not to the subject of how to work together for a common goal. Project 2 shows that individuals changed and embraced the demands of their role. The inclusion of the Leadership Team (layer 2) by Senior Staff infused the sense of responsibility across the board. Members of all teams in the holarchy connected with their own sense of purpose and became aware of their impact.

In the Unity with Others dimension, Project 1 also shows a low score. This came from the interview questionnaire data that pointed to a set of individuals who recognized the importance of the project but could not leave their own ideas and their functional membership behind to come together as a cohesive collective. The leadership team in Project 1 could not agree on any shared values and belonging to the team was not viewed as important, particularly by the third layer of the holarchy. In contrast, Project 2 shows a higher score for the Unity with Others dimension. As previously stated, all layers for this project came together with a common purpose and developed the shared value of accountability. No one wanted to let others down, particularly with Senior Staff and the CEO fully engaged. The unity exhibited by the holarchy in Project 2 appeared to be one of purpose and not of identity.

Both projects received medium to high scores in the Expressing Full Potential dimension of the Map of Meaning. Medcab, being a high-tech company, focusing on deliverables rather than relationships is natural for the company. Project 2 obtained a slightly higher score than Project 1 for this dimension. As all of the interviewees noted, developing products is in Medcab’s DNA. In contrast, several of the interviewees observed that process reengineering, the main objective of Project 1, did not come naturally.

The final dimension of the Map of Meaning is Service Others. This is a dimension that goes outside of the company and positions the organization to work for the greater good. Neither change initiative in the case study had elements of going outside the company. Project 1 was an inwardly focused project while Project 2, at its core, had the objective of revamping the company’s product offering. In the rating, Project 2 received a slightly higher score because there was thought about the impact to others and how the new products could positively affect the lives of Medcab’s customers and their customers. In Project 1 team members were aware of the company’s greater good and could see it in the horizon. However, they were not able to translate this greater benefit in terms of their own engagement.

Leadership Stage Development Analysis

A set of the questions for the participants in the case study aimed at uncovering what leadership stages, as defined by Torbert and his colleagues, were present in the leadership teams of the two transformational initiatives (Torbert & Associates, 2004; Rooke & Torbert, 2005). Only four of the seven leadership stages were being investigated in this case study. It is the opinion of this researcher that the characteristics of the Opportunist and Diplomat do not map to roles that would be imperative in a transformational leadership team. The presence of the Alchemist was also excluded given that this stage of leadership is present in only one percent of leaders and the likelihood that an Alchemist was present in the Medcab initiatives and could be recognized as such was low. The actions of an alchemist would most likely be interpreted as an Individualist or Strategist (Torbert & Associates, 2004).

Table 3 shows the results of the answers about leadership stages provided by the Medcab participants (see Appendix F for a summary of the answers). From these answers, it is clear that Project 1 did not have all of the Experts available during the project. This feedback by the participants was unanimous. The lack of critical expertise in this initiative was evident in both the internal resources and the consultants that were engaged in Project 1. In contrast, Project 2 included all of the experts necessary to achieve its objectives. As mentioned earlier, the company has deep expertise in product development and felt comfortable in stretching to improve its ability to handle parallel product development and in improving its time to market cycle time.

Table 3. Presence or absence of the leadership stages for each transformational initiative at Medcab. This table provides a rating of the findings for the leadership stages for each initiative. A rating of 1 indicates the total absence of the leadership stage characteristics based on the input provided by the participants to the questions related to each stage. A rating of 2 specifies about a 25 percent presence of the leadership stage. A 3 in the rating columns indicate about 50 percent presence, while a 4 corresponds to 75 percent. A rating of 5 states that full presence (100 percent) of the leadership stage was determined during the interviews.

| Leadership Stage |

Rating for Project 1 |

Rating for Project 2 |

| Experts |

2 |

5 |

| Achievers |

3 |

5 |

| Individualists (Architects) |

1 |

3 |

| Strategists |

3 |

4 |

Table 3 shows that Project 1 did have enough Achievers to drive the project to completion. However, these Achievers were not able to create a common understanding of the priorities and drivers for the project. Further, several of the interviewees stated that people in the project believed that the dates in the project were not real and that they could slip. Project 2 had a markedly different Achiever result. The head Achiever in the project was the CEO. He made clear that everyone knew what was at stake and what needed to be done and by when. There were no doubts from the leadership team on what was expected.

The characteristics of the Individualist are harder to pin down in a set of questions. For instance, how do people understand and recognize relativism? To clarify matters, this researcher encapsulated the traits of an Individualist in the role of a solutions architect. This type of individual exemplifies the attributes of an Individualist leader. A solutions architect has to be able to consider multiple points of view, be consultative, approach situations systematically and be able to bring everyone together in a cohesive approach. This type of role has to be able to see the goodness and the risks in the views of others without alienating anyone.

From the interview responses, it became clear that Project 1 did not have a solutions architect. No one in the leadership team could see the big picture or could assemble the necessary details to articulate a path for everyone. Consequently, Project 1 experienced multiple paths, multiple solutions and a fair amount of controversy. The results of Project 1 were deeply impacted by the lack of this leadership stage.

Using the same line of inquiry, the researcher was able to uncover that Project 2 did not have an architect to bring the multi-product launch together either. When Senior Staff created the missing second layer with the Leadership Team, it was this team that was able to architect the global launch solution. There was not a single architect but a number of them collaborating in an achievable solution.

From the Strategist stage perspective, both projects had vision and strategies that were communicated and maintained throughout their execution. Project 1 was more complicated than Project 2 and required the translation of the strategy into digestible chunks. Many of the Project 1 participants got lost in the details and could not relate to the overall strategy. Several of the case study participants stated that at least half of the people did not know what they and their functions were getting out of the project. In Project 2, the subject matter was known to all participants. The vision and strategy of this initiative was communicated by the CEO and his Senior Staff often. Interviewees commented that everyone was on board and that there were no doubts in everyone’s mind as to what was at stake. From the responses of the case study questionnaire, both projects missed understanding the needs of the people in the projects. This lack of understanding was deeper in Project 1, but the Project 2 leaders did not see the level of stress that the team members were under. One of the comments was that at times Project 2 felt like being at the dentist: “you know it is good for you but you can’t wait for it to be over.”

Conclusion

This research aimed at answering two questions: a) how leadership stage development correlates to the success of transformational change initiatives, and b) how the make-up of a change leadership team affects outcome in the absence of leadership stage development awareness. The case study at Medcab dealt with two transformational initiatives with different outcomes. Project 1 and 2 at Medcab shared key similarities including their importance to the company, proper funding and support from their executive team. As explored in the analysis sections of this document, the projects were dissimilar in their Map of Meaning and their leadership stages. These two lenses were used in the case study to address the questions posed by the research.

Using Figure 4 as a reference, Project 1’s Map of Meaning shows a weak Being dimension. Both, the Inner Development and Unity with Others quadrants received low ratings based on the answers from the participants. This overall weakness manifested into low awareness, individual agendas, inability to come together, minimal to no ability to grow, and limited learning. In particular, Project 1 had a low score in the Inner Development quadrant. This prevented this initiative from developing an identity that team members could relate to and to which they wanted to belong. The dimension of Doing in Project 1’s Map of Meaning showed some strength, particularly in the Expressing Full Potential quadrant. This strength enabled the project to develop its work products and complete them by a given due date. As documented in the analysis section, the work products and team readiness for this initiative had issues that resulted in major challenges right after the new system and processes went into effect.

From the leadership stages perspective, Project 1 did not have all of the Experts it needed. It appears that it had enough Achievers but they were not effective in convincing team members what to accomplish and by when. This difficulty could have been rooted in the company’s culture but it appears that Achievers in the leadership team were not collaborating or aiming for the same goals. It was noted in the analysis that Individualists as incarnated in one or more solutions architect were totally absent from Project 1. This void prevented this initiative from having a holistic solution that drove work products and team engagement. Finally, there is evidence of the presence of Strategists in Project 1 from the established vision and the overall strategy for this initiative. However, this leadership stage was not able to create a cohesive collective.

Integrating the Map of Meaning and leadership stage lenses, we can conclude that the development of the Being dimension in Project 1 was affected by the absence of the Individualist stage and by the ineffectiveness of the Strategists on the team to create a cohesive collective. The Doing dimension for this initiative was more developed due to the availability of some Experts and a number of Achievers. This allowed Project 1 to deliver work products but with limited completeness and accuracy. This was due to the emphasis in the Individual dimension of the Map of Meaning over the Collective. The fact that the leadership team for this initiative could not get its Collective dimension engaged, ultimately translated into the diminished capabilities of the new system and processes being put in place.

The Map of Meaning ratings in Table 2 shows a stronger set of Being and Doing dimensions for Project 2. This is also true for the Individual and Collective dimensions of this holon. This indicates that the leadership team in this initiative had a strong sense of identity, was able to accomplish results and could work well with others. The rating of 3 for the Inner Development quadrant corresponds to a team that had enough awareness to guide its own course and learn as it went along. The strong rating of 4 associated with the Unity with Others quadrant reflects a team that was effective, shared common values, and could pursue unified goals. On the Doing dimension of the Map of Meaning, Project 2 shows a strong Expressing Full Potential quadrant that correlates to solid execution, complete and accurate work products, and active management of risks. As stated in the analysis, this initiative along with Project 1 did not score high in the Service Others quadrant given their technical scopes. However, Project 2 had enough collective awareness of the each individual’s impact to the whole to score higher than its project counterpart in the case study.

From the leadership stage perspective and as noted in the analysis, Project 2 had all of the Experts it needed. This supply of expertise came from all three layers of the leadership holarchy, but, primarily the second layer. The abundance of Experts made the deliverables of Project 2 completely realizable. The Achiever stage was also well represented in this initiative starting with the Medcab CEO who participated in the daily leadership meetings. This translated into a fast paced execution with well-defined milestones. Even though the Individualist level in Project 2 was not manifested into identifiable solutions architects, the members of layer 2 of the holarchy provided the Individualist action logic aplenty. The results of this abundant Individualist energy were complete solutions, a fair amount of introspection and overwhelming critique for everyone’s work. The last leadership stage investigated in the case study, the Strategist, was well personified in the senior team members of Project 2. Vision and strategy were well defined, communicated and globally accepted.

Looking into the intersection of the Map of Meaning and the leadership stage development lenses, we can conclude that the Experts and Achievers in Project 2 provided a strong backbone for the Doing dimension of the Map of Meaning. Similarly, the team-oriented version of the Individualist stage and the effective Strategists in this project gave way to a solid Being dimension of the holon. The Individualist energy supported the development of Inner Development quadrant while the Strategist level created the environment for effective collective activities.

On the first question of the research, we can conclude that the stage development as analyzed through the Map of Meaning and leadership stage lenses affected the outcome of both initiatives. Project 1 had missing leadership stages and underdeveloped Map of Meaning quadrants both limiting how much this initiative accomplished and how challenged was its output. In contrast, Project 2 did not have any missing leadership stages and showed strength across three of the Map of Meaning quadrants. This initiative was successful and met all of its objectives.

On the second question of the research, we can also conclude that the leadership team make-up impacted the outcome of the initiatives. Medcab did not have any awareness of leadership stages prior to this case study. The assembly of the leadership teams for both projects followed criteria that did not consciously include all leadership stages. Project 1 suffered the effects of missing Experts and the absence of Individualists. On the other hand, Project 2 had the benefit of the Medcab Senior Staff forming layer two of its team holarchy with a highly qualified Leadership Team. This new leadership layer came together only in the last four months prior to product launch but was able to guide the project to success. It appears that all of the leadership stages in Project 2 became present through the combination of the Leadership Team members and Senior Staff.

This research opens the door to further investigation on how to assemble transformational team holarchies that have the best chances for success. Future research could focus on practical mechanisms to identify the leadership stages of potential leaders in a transformational team. Additionally, this research did not provide any guidance on the number or roles of the leaders at the various leadership stages. It is easy to conceive that Experts in all of the domains for a given scope would be required in a leadership team. However, what is the right number of Achievers and what should their roles be? This and other important questions could guide additional research on a topic that promises improving the outcome of transformational changes to a number greater than one in three.

References

Aiken, C. & Keller, S. (2009). The irrational side of change management. The McKinsey Quarterly, (2), 1-9.

Barker, E. H. & Torbert, W. R. (2011). Generating and measuring practical differences in leadership performance at post-conventional action-logics. In Pfaffenberger, A., Marko, P., & Combs, A. (Eds.). The post conventional personality: Assessing, researching, and theorizing higher development. Albany, NY: Suny Press.

Burke, W. (2011). Organization Change Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Cacioppe, R. & Edwards, M. G. (2005a). Adjusting blurred visions: A typology of integral approaches to organisations. Journal or Organizational Change Management, 18(3), 230-246.

Cacioppe, R. & Edwards, M. G. (2005b). Seeking the Holy Grail of organisational development: A synthesis of integral theory, spiral dynamics, corporate transformation and action inquiry. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 26(3), 86-105.

Capitalizing on complexity: Insights from the global Chief Executive Officer study (2010). IBM.

Doppelt, B. (2003). Leading change towards sustainability: A change-management guide for business, government and civil society. Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf.

Edwards, M. G. (2005). The integral holon: A holonomic approach to organisational change and transformation. Journal or Organizational Change Management, 18(3), 269-288.

Edwards, M. G. (2009). Seeing integral leadership through three important lenses: Developmental, ecological and governance. Integral Leadership Review.

Gambrell, K. M., Matkin G. S. & Burbach, M. E. (2011). Cultivating leadership: The need for renovating models to higher epistemic cognition. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 18(3), 308-319.

Harung, H., Travis, F., Blank, W., & Heaton, D. (2009). Higher development, brain, integration, and excellence in leadership. Management Decision, 47(6), 872-894

Henderson, G. M. (2002). Transformative learning as a condition for transformational change in organizations. Human Resource Development Review, 1(2), 186-214

Isern, J. & Pung, C. (2007). Driving radical change. The McKinsey Quarterly, (4), 1-9.

Kegan, R. (2000). What “form” transforms? A constructive-developmental approach to transformative learning. In Mezirow, J., & Associates. Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Koestler, A. (1990). The ghost in the machine. London: Penguin.

Kotter, J. P. (2006). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, (The Best of HBR ed.).

Lichtenstein, B. M. (1997). Grace, magic and miracles: A “chaotic logic” of organizational transformation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 10(5), 393-411.

Lips-Wiersma, M. & Morris, L. (2011). The map of meaning: A guide to sustaining our humanity in the world of work. Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf.

Meaney, M. & Pung, C. (2008). Creating organizational transformations. McKinsey Global Survey Results. 1-7.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000), Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of adult learning theory. In Mezirow, J. (Ed.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Mezirow, J., Taylor, E. W., & Associates. (2009). Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Nailon, D., Delahaye, B. & Brownlee, J. (2007). Learning and leading: How beliefs about learning can be used to promote effective leadership. Development and Learning in Organizations, 21 (4), 6-9.

Pandey, A., & Gupta, R. K. (2007). A perspective of collective consciousness of business organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 80, 889-898.

Pruzan, P. (2001). The question of organizational consciousness: Can organizations have values, virtues and visions? Journal of Business Ethics, 29(3), 271-284.

Rooke, D. & Torbert, W. R. (1998). Organizational transformation as a function of CEO’s developmental stage. Organization Development Journal, 16(1), 11-28.

Rooke, D. & Torbert, W. R. (2005). Seven transformations of leadership. Harvard Business Review, April, 1-12.

Sarros, J. C., Cooper, B. K. & Santora, J. C. (2008). Building a climate for innovation through transformational leadership and organizational culture. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 15 (2), 145-158.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership: Vol. The Jossey-Bass business & management series ; (4th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday.

Simcox, J. (2005). Detailed descriptions of the developmental stages or action logics of the leadership development framework. Presented at the W. Edwards Deming Research Institute, Eleventh Annual Research Seminar, Fordham University Graduate Business School, Lincoln Center, New York City.

Torbert, B. & Associates. (2004). Action inquiry: The secret of timely and transforming leadership. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Torbert, W. R. & Taylor, S. S. (2008). Action Inquiry: Interweaving Multiple Qualities of Attention for Timely Action. Retrieved from http://www.harthill.co.uk/assets/files/Articles/ActionInquiry_InterweavingMultipleQualities_ofAttention_Torbert_and_Taylor_2008.pdf

Vinson, M. & Pung, C. (2006). Organizing for successful change management. A McKinsey Global Survey.

Wilber, K. (2000). A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science, and spirituality. Boston: Shambhala.

Appendix A – Interview Questions

The following are the questions which were asked to each participant during the one hour interviews along with the estimated duration for each question group:

Participant qualifications (5 minutes)

- What is your role with the organization and how long have you been in this role?

- How do you define transformational change and what makes it be successful?

- Where do you see you can contribute the most in a transformational initiative and why?

- As a leader, what personal attributes do you bring to your organization?

Transformational project characteristics (30 minutes) – The questions in this group were asked to the research sponsor and only two of the other participants.

- At a high level, describe the scope of the two transformational initiatives in the study in terms of locations, functions, processes, systems and organizations.

- Were the targeted transformations successful; why or why not?

- What interventions were required to accomplish the goals of the initiatives, where did they come from, and how were they applied?

Context of your involvement (10 minutes) – The questions in this group were asked for each initiative.

- Describe your role in the change initiative.

- What are your main observations in how the organization approached its transformational change?

Project leadership structure (30 minutes) – The questions in this group were asked to the research sponsor and two of the participants for each of the initiatives.

- Governance lens: Describe the leadership team organization for the transformational initiative. Specify the governance layers. Do you know how the team members of this leadership team were selected? What was missing from this structure?

- Ecological lens: How was the interaction between the layers of the leadership team? How did the leadership team interact with the company’s functional and executive leaders? What are the high-lights and low-lights of the leadership team interaction with its environment?

- Learning lens: How did the leadership team learned? Was there a concerted effort by the team to learn and if so, how did this happen? What are the main things the team learned? What did the team missed learning?

Leadership characteristics in the transformational project (45 minutes) – The questions in this group were asked for each transformational initiative.

- Inner self-development: What were the driving forces for the leadership team to accomplish the goals of the initiative? What level of awareness did the leadership team have on the needs of its constituencies? How were decisions made by the leadership team? What was the balance between the needs of the project and the needs of the team members?

- Unity with others: What did the leadership team value the most from its team members? How did the leadership team relate to “others” in the organization? How were opinions and ideas from different levels of the organization handled? Did the leadership team create a sense of community and if so how?

- Expressing full potential: How did the leadership team manage its objectives? What work standards did the leadership team held itself and others to? How did the leadership team deal with the “low” points during the project? Were there higher level company goals the leadership team felt connected to?

- Service others: What kind of responsibility did the leadership team feel it had with the global organization? What was the leadership team’s view of the systems and processes in the transformational project? To what extend did this team work to integrate their work products with the rest of the company’s and externally?

- Leader stage development: How was the leadership team staffed to have all the experts it needed to accomplish its objectives? Who created the sense of urgency for the initiative and were these individuals effective? Did the leadership team have one or more individuals identifying potential risks? Was their early warning accepted and useful? Who provided the overall strategy for the initiative and guided its journey? What was effective from these individuals and what was not?

Appendix B – Characteristics of Transformational Projects

The following set of characteristics was used in determining the level of transformational change involved in the projects that were assessed as part of the participant interviews. These characteristics are based on the transformational change definitions from Burke (2011), Doppelt (2003), and Kotter (2006).

- Results in transformation of the organizational culture

- Introduces fundamental change in the organization’s strategy

- Results in significant changes in processes and systems

- Affects organization as a whole or a significant portion

- Change is introduced over a considerable period of time (> 2 years)

- Requires large investment of people and physical resources

- Benefits of change are significant

- Consequence of failing with the change could be disastrous

- Outside expertise is required to accomplish the change

- Major developmental opportunity for the organization’s leaders

Appendix C – Participant Criteria

The following is the criteria provided to the research sponsor to facilitate the selection of the participants:

- Senior role in the organization

- Member of both of the transformational change initiatives. Alternatively, member of one of the initiatives.

- Held a leadership role in the change initiative(s) at level one or two of the leadership team holarchy.

- Individual is known for being insightful and can effectively communicate organizational experiences.

Appendix D – Participant Organizational and Change Initiative Roles

Current roles and roles in the transformational initiatives for the five participants in the case study.

|

|

Current Role |

Project 1 Role |

Project 2 Role |

|

Person 1 |

CFO |

Project Sponsor and Steering Committee Member |

Sr. Staff Member |

|

Person 2 |

Executive Vice President, Field Operations |

Steering Committee Member |

Sr. Staff Member |

|

Person 3 |

Sr. Director, Information Technology (IT) |

Program Director |

IT Leader on Leadership Team |

|

Person 4 |

Sr. Director, Field Operations |

Field Operations Leader |

Field Operations Leader on Leadership Team |

|

Person 5 |

Sr. Manager, Cost Accounting |

Program Management Office, Finance |

Finance Leader on Leadership Team |

Appendix E – Map of Meaning Interview Summary

Map of Meaning summarization for the transformational change initiatives at Medcab along with the rating of how developed each dimension appears to be based on the input provided by the participants. The ratings specify: 1 – no evidence of any development during the project; 2 – about 25 percent development; 3 – about 50 percent development; 4 – about 75 percent development; and 5 – full evidence of a developed dimension.

| Map of Meaning Dimension | Project 1 |

Rating |

Project 2 |

Rating |

| Inner Development | The leadership team was not fully aware of its role and how to go about driving change for the company. Multiple agendas were present and personalities dominated conversations. There were minimal to no transformations that took place. There was some technical growth. |

1 |

Initially, the leadership team for this project did not have full awareness on how to successfully complete the objectives. The awareness of the Senior Management team changed the leadership constituency, bringing more awareness of what it would take to be fully successful. Growth in the dimension of team collaboration was evident. Individual growth was limited. Some leaders stepped out from their comfort zone and embarked on remarkable work. |

3 |

| Unity with Others | Team was connected through the project deliverables. Although effort was placed in building community, this did not take place. People espoused different values and aimed for different goals. Most team members did not have a sense of belonging in the project team. This changed after go-live when team members spent 1-year together solving the problems introduced by the project. |

2 |

Initially, the core team was not aware of the needs of others and could not create a cohesive work team. Senior Staff and the larger leadership team achieved work cohesiveness, although it was not a work community. Unity of purpose was achieved through work products and daily meetings. Personal commitment was the main shared value all the way from the CEO. |

4 |

| Expressing Full Potential | A fair amount was accomplished by the team. However, misalignment with the objectives made some of the teams under-perform. Some critical areas received focus and creativity. Others were ignored and left for later. Personal agendas prevented coherent work and mutual leverage. |

3 |

Goals were clear, particularly after the broader team was brought together. People worked for the common goals. Teams executed at their best under much of pressure. Time compression and the need to succeed (not fail) created a fair amount of stress. Problem solving resulted in a fair amount of creativity. Direction and influence was provided by the leadership team acting in unison. |

4 |

| Service Others | Some of the leadership team had a strong sense of the common purpose and the global benefit for the company. However, this was not a global view. A fair number were concerned of what would happen to them when the change occurred. Also, some had the expectation that someone would deliver the change for them and therefore they did not need to be engaged. |

2 |

After the larger leadership team was engaged, everyone understood that the company would be positively or negatively impacted. The leadership team had a strong sense that their contribution made a difference. Even though the new products would contribute to the industry, there was a stronger sense of what it meant to the company as opposed to Healthcare. |

3 |

Appendix F – Leadership Stage Development Interview Summary

Presence or absence of the leadership stages for each transformational initiative at Medcab. This table provides a summary of the findings for the leadership stages for each initiative along with a rating. A rating of 1 indicates the total absence of the leadership stage characteristics based on the input provided by the participants to the questions related to each stage. A rating of 2 specifies about a 25 percent presence of the leadership stage. A 3 in the rating columns indicate about 50 percent presence, while a 4 corresponds to 75 percent. A rating of 5 states that full presence (100 percent) of the leadership stage was determined during the interviews.

| Leadership Stage | Project 1 |

Rating |

Project 2 |

Rating |

| Experts | Missing business expertise in the consultants. Business and IT did not know SAP. Intersection of knowledge deficit created large solution gaps. Solutions could not be completely conveyed. |

2 |

In the first part of the project not all experts were involved. Once Senior Management became a driving force, all the experts were engaged either directly in the leadership team or through the leaders in the “room.” There were no expertise gaps. |

5 |

| Achievers | Sense of urgency and drive was in place via the go-live date and pressure from the leadership. However, there were multiple interpretations of the sense of urgency and why the project was being done in the first place. This led to mixed levels of engagement and broad procrastination. |

3 |

Urgency and overall drive came all the way from the CEO. Senior Staff was fully engaged and provided the forcing function for everyone’s sense of urgency. The benefits and the risks to the company were understood by all and managed daily. |

5 |

| Individualists (Architects) | There was no single architect or solution designer. There were a number of contributors, all of which had their own ideas on how the solution should work. Risks were not well understood and unintended consequences were mostly hidden. |

1 |

This project also lacked an overall architect or solution designer. However, once the global leadership was formed, the solutions’ architects for each area were engaged. This allowed for all risks to become known and managed. The lack of a cohesive solutions resulted in second guessing the experts. |

3 |

| Strategists | There was an overall strategy and vision. Generally people understood the vision but everyone got lost in the details. The vision and overall strategy were not translated into digestible “chunks” that the organization could understand and contribute to. |

3 |

The vision was known to all. Some critical strategies were missing until the global leadership came together. Strategies were developed “live” with the leadership team in the daily meetings. This enabled global understanding of the strategies and their full support. |

4 |

About the Author

Jorge Taborga is the Vice President of Manufacturing, Quality and IT at Omnicell, Inc. He has an extensive background in change leadership, product development, management consulting, process reengineering and information technology. His 29 year work experience includes companies like ROLM Systems, IBM, Quantum, Bay Networks, 3Com, and UTStarcom. Jorge also delivered organizational development and management consulting services to a number of companies in the San Francisco Bay Area and China. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Organizational Systems at Saybrook University.