Book Review: Spirituality and Business: Exploring Possibilities for a New Management Paradigm

Brian Van der Horst

Sharda S. Nandram and Margot Esther Borden, Editors. Spirituality and Business: Exploring Possibilities for a New Management Paradigm. Berlin: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg Publishers, 2010

Brian Van der Horst

Writing about spirituality and business has always seemed to me about as easy as nailing Jello to a wall. However, the editor/authors of this book have done a noble academic job of collecting a wide variety of examples and approaches to facilitating and utilizing personal evolution in the workplace.

Writing about spirituality and business has always seemed to me about as easy as nailing Jello to a wall. However, the editor/authors of this book have done a noble academic job of collecting a wide variety of examples and approaches to facilitating and utilizing personal evolution in the workplace.

Dr. Sharda S.Nadram is an associate professor at Nyenrode Business Universiteit in the Netherlands, the founder of a Dutch consulting firm, Pram, and the coeditor of “Business Spiritualiteit Magazine.” Her other books include “The Spirit of Entrepreneurship,” and “Kautilya’s Arthashastra” about a political strategist, economist, educator and an expert in diplomacy, who lived in India around 300 BC.

Co-editor Margot Esther Borden is a transpersonal and integral psychotherapist based in Paris, where she founded the consulting company Integral Perspectives. She teaches at Antioch McGregor University in Ohio and gives public seminars throughout Europe, India, and the U.S.

Nadram says “her field of expertise concentrates on research, education and projects on spirituality in business: empowerment, transformations learning and yoga, the holistic entrepreneur, servant leadership, entrepreneurial personality, and growth.”

Quite a mouthful. But so is this book.

Here’s a quote from the foreword to this compilation.

“Now, more than ever there is an urgent need to revive spirituality in business as in all aspects of life. It is sometimes thought that spirituality is incompatible with profit making. However, in the current economic downturn, as businesses face the challenge of restoring people’s faith and confidence, spirituality can play a key role. Trust is the breath of business, ethics its limbs, and to uplift the spiritual, its goal.”

— H. H. Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, founder International Association for Human Values.

This attitude has been a global movement, at least since the late 1970s, when some of my colleagues and futurists were talking about consciousness, mysticism, shamanism and spirituality in business. When I produced a series of conferences by Willis Harman for the Stanford Research Institute on new paradigms in business, we often found top executives—in contrast to middle management—of Fortune 150 companies were often considerably invested in producing spiritual evolution in their organizations as well as profit.

In the 00’s many large companies came out of the spiritual closet. Many of them were cited in Megatrends 2010:The Rise of Conscious Capitalism by Patricia Aburdene (published in 2005), including Ford, American Airlines, Texas Instruments, Coca Cola, and the usual suspects like Ben & Jerry’s, and Calvert Social Investment Funds. Aburdene was talking about trends such as “the power of spirituality, conscious capitalism, spiritually in business, conscious management styles, and socially responsible investment.”

Both editors have extensive experience consulting to huge inter- and multi-national companies, so they know of which they speak They have divided this collection of 20 monographs and academic articles into three sections: Concepts of Spirituality, Personal Spirituality, and Spirituality and Leadership.

Many of the authors in Nandram and Borden’s rather academic volume are still talking about how they would study spirituality in business, rather than how to make it work. But many also demonstrate how much spiritually has been embraced by employees from the top to the bottom of the corporate ladder.

The first section offers various definitions of spiritually in the workplace and benefits thereof: increased creativity, accountability, motivation, commitment to the job, honesty, trust and personal happiness and fulfillment. In the keynote chapter, the editors give exhausting lists of management and academic journals, corporate programs, and management school research projects that take spirituality in business seriously.

Nadram’s first chapter promises a potpourri of modalities for defining or researching spirituality, but delivers a list of labels and abstractions that generally boil down to feeling happier inside and being nicer to people on the outside. American integral theorists will note that Willis Harman’s approach is code-coherent with the Four Quadrants approach. Oriental theorists can find Aurobindo’s flavor (he was, after all the first guy to come up with the label “integral psychology’ in the 1930s.) Both Nadram and Borden have spent some time studying at the Auroville ashram in India, so their frequent citations of “integral approaches” are mostly Aurobindo’s style of the great chain of being (spirit/soul/mind/body) and more elevated levels of consciousness.

Advocates of the western integral tradition will find no more than a few Ken Wilber quotes and several pages on spiral dynamics.

Some examples of the contributor’s writings: Margaret Benefiel teaches spirituality at a theological school in Boston, holds the chair in Spirituality at the Miltown Institute in Dublin and is the author of Soul at Work. In her chapter, “Methodological Issues in the Study of Spirituality at Work,” she proposes a new academic field of “Spirituality at Work”. In Chapter 4, S.N. Balagangadhara, a professor at Ghent University in Belgium who specializes in cultures and religion, compares the western Maslow hierarchy of human needs with the models of attaining inner peace and happiness from India. Others write about synchronicity, self-organizing companies, the Socratic Method and ethics dilemmas in familiar conversations.

Part II addresses how spirituality at the individual level is being applied by various authors in the corporate context. Most of the models described revolve around traditional activities of yoga, breath work, meditation, team-building, experiential workshops, exercise and nutrition. Some inventors of different disciplines present their work: at Shell Oil, the AWARE (At Work As Responsible Employees) program; the APEX (Achieving Personal Excellence) seminars at Merrill Lynch, JP Morgan, Reuters, Capgemini, and other multinationals: Integral Transformational Coaching (no relation to the Leonard/Murphy or Wilber approaches); Buddhist Dharma approaches; and “Ontological Coaching, ” to name a few. While several writers cite evaluation studies and up to a year’s follow-up studies, most of their data comes from either self-evaluations or “happy sheet” exit surveys. Their results are detailed as decreased stress, more energy, greater team spirit, clarity of mind, better relationships, happiness, confidence, and satisfaction.

A friend of mine, a trader at one of the world’s biggest hedge funds, is doing his PhD thesis on whether socially responsible businesses really make more money than others.

In his first research he finds that while subjective evaluations such as market valuations do increase, he is hard put to find any objective qualitative evidence to support these market beliefs.

Similarly the authors of this compilation have few bottom-line statistics with which to make their case. But motivation, after all, is based on subjective value judgments. People choose one option over another because they find the choice selected more valuable than the other members of the decision set. So to the extent that these programs aid people to shift values toward those ancient ideals of love, compassion, charity and service, quantitative evidence may be irrelevant to their desired outcomes.

One of my favorite definitions of business comes from the Business Dictionary (www.businessdictionary.com): An economic system in which goods and services are exchanged for one another or money, on the basis of their perceived worth. Every business requires some form of investment and a sufficient number of customers to whom its output can be sold at profit on a consistent basis.

The key word here is “worth.” No matter how you slice it, we’re talking about a subjective decision.

The third and last section of this work is entitled “Spirituality and Leadership.” Here the editor/authors detail case studies of their personal innovations. Borden describes her “Integral Development Index,” and how she used it with one of the worlds largest consumer brands corporations. Nandram recounts how she brought Integral Transformational Yoga to improve leadership style at Wipro Technologies, a $15 billion- valued, 108,000 employee, India-based multinational that describes itself as “the #1 provider of integrated business, technology, consulting, testing and process solutions on a global delivery platform.” Contributors Ashish Pandley and Kuku Singh report on their Wholesome Leadership Development Process at the German multinational Sew-Eurodrive, which manufactures engineering goods in India, wherein they employed such established tools as the MBTI and 360-degree Assessment psychographics. Suzan Langerberg, a consultant for Diversity SME in Belgium and who studied history, philosophy of human science and two contract studies in sexology and developmental psychopathology, leans on the famed S & M philosopher Michel Foucault to present how at a 100,000 employee steel company she used her “Model of Critique in Business,” She defines this as a practice that “brings together moral judgment, courageously speaking the truth, and reason.” Nandram and Jan Vos write the penultimate article in this volume “The Spiritual Features of Servant-Leadership,” citing examples of historical servant leaders such as Confucius, Aristotle, Cicero, Thomas Jefferson, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Mother Teresa, and Nelson Mandela.

Nadram and Borden end this work with “Epilogue: Ingredients of a New Paradigm” with the obligatory call for further research, and summarize their presentation as departing from the trend in spiritual development models of focusing on individuals and have instead oriented their efforts toward “leaders, managers, employees and organizations.”

“Spirituality,” they say, “… is a process of designing one’s activities in such a way that they are aligned with the authentic Self (of the individual or the business). We emphasize this point through these four main processes:

“Psychic process consists of finding the authentic Self by exploring it though a variety of tolls such as meditation, yoga, prayer…

“Mental process: consists of an evaluation of the facilities and sources needed to fulfill the needs of the authentic Self.

“Vital process: is about bringing balance and a continuous connection between the authentic Self and the needs of the environment.

“Strategy or physical process: consists of concrete steps in terms of behaviors and values to implement and align thought, word, and action to the authentic Self.”

The emphasis on “the authentic Self” here is mine. Because I have a few points to make.

The first point is that the five above paragraphs are straight from the Aurobindo great chain model of integral spirituality. While this is all good for creating a map of personal spiritual development, it is an incomplete model of business. While it deals with one spiritual belief system for investigating personal evolution in the context of business, it excludes by omission many other approaches such as mysticism, kabbalah, martial arts, zen, psychedelics, Sufism, shamanism, Islam, and Existentialism, to name a few. Sorry ladies, this book is a tad ethnocentric. Then again, this work does stand out as a great introduction to finding out how Indian yoga and Vedanta is being used in business these days.

My second point is that “authentic self” is a very abstract, fuzzy, and limited model of personal evolution. Sure, “you’ll know one if you feel one.” But that’s privileged, highly introspective information. I don’t think other people are relevant judges of one’s own authenticity. And anyway, I doubt if the concept of inauthenticity is very useful.

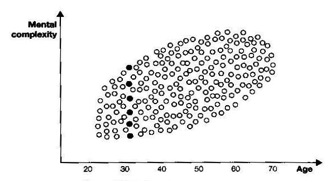

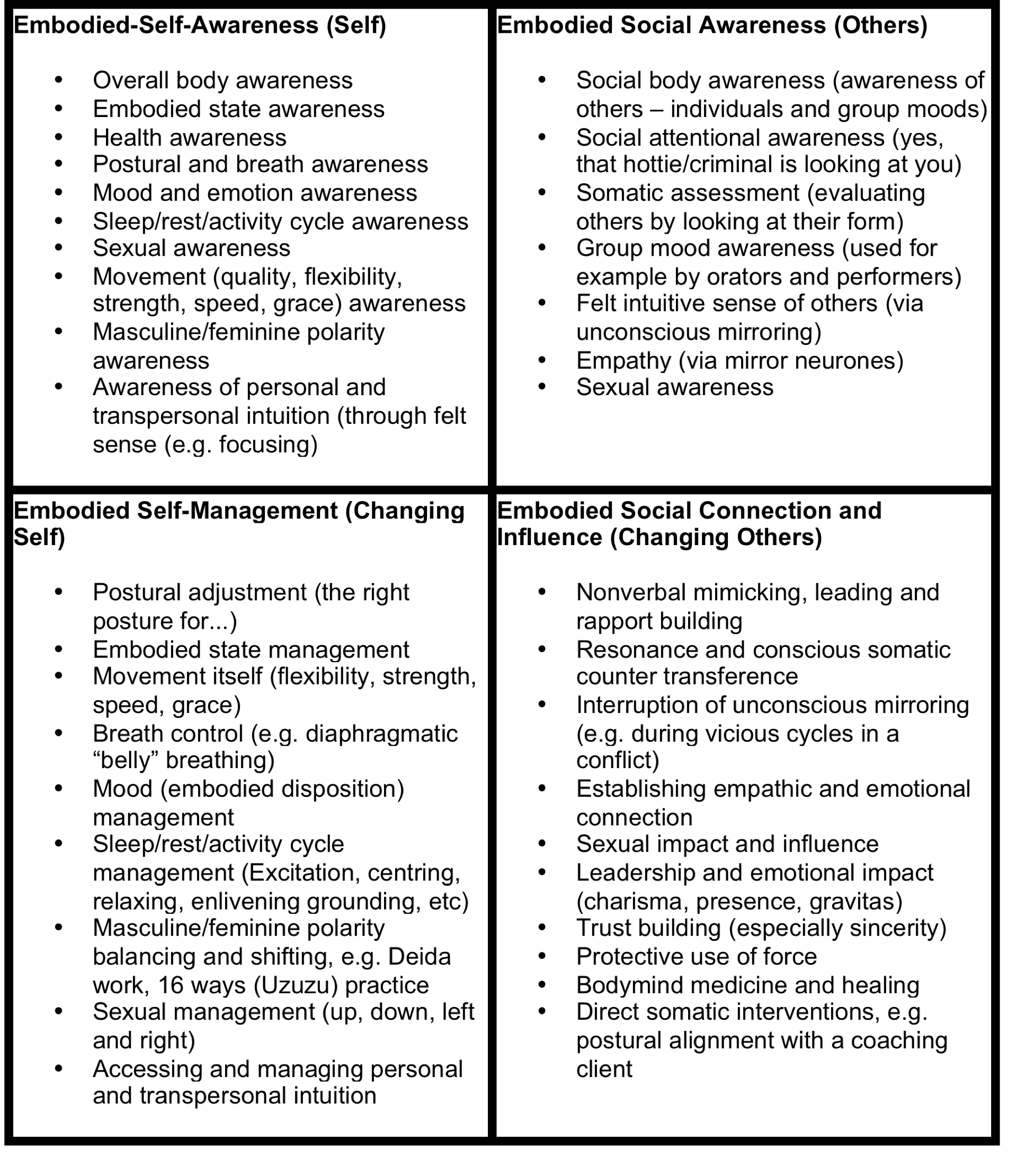

My third point, especially for our integral readers here at this publication, is that while the authors deal with the culture of what they call “the burgeoning field of Business Spirituality,” there is a lot missing about the personal experience of spiritual evolution; the objective, quantitative domains of business; and the systemic organizational structure of the work of you and your colleagues in this opus. In Western terms, in my opinion, this book is more about the lower left quadrant of the current integral model, and very little about the other three:

For example, here’s what Alain Gauthier and Joan Kenley call Positioning the Five Business Learning Disciplines in the Integral Framework in their seminars about using the Wilberian integral model in business.

Here’s how Ken Wilber describes management approaches in several recent oeuvres, including “The Integral Vision:” (Shamballa, 2007, p.98) and in recent publications from his Integral+Life organization: http://integrallife.com/apply/business-leadership)

I know Nandram and Borden never intended to do a book about western integral spirituality, and they have succeeded in writing and compiling an extraordinary survey of eastern spirituality. All I’m saying is that if they are calling it Integral Coaching, or Leadership, or Marketing, or whatever, they might consider what the other half of the world (yeah and I know, only 14 % of the global population is from the western hemisphere, and 21% from Europe) calls integral.

For the rest of us, it’s a great introduction to what more than 57 % of the people on this planet call spirituality in business.

About the Author

Brian Van der Horst has been an executive coach since 1977, and an NLP trainer since 1984 when he began to live and work in Europe, based in Paris where he founded Repère, an international NLP training institute, with two French consultants, designing and teaching practitioner and master practitioner certification programs to more than 10,000 people world-wide. In 1994, he founded a coaching school, and has certified around 300 coaches.

For the past few years, he has been an Program Development Director for Renaissance 2; and a founding member and Chief Facilitator, Europe, for Ken Wilber’s Integral Institute. Previously he was director of the Neuro-Linguistic Programming Center for Advanced Studies in San Francisco, and a consultant with Stanford Research Institute in the Values and Lifestyles Program of the Strategic Environments Group.

[…] review of Edgar Morin’s La Voie. Pour l’avenir de l’humanité—Michel Nguyen TheSharda S. Nandram and Margot Esther Borden, Editors, Spirituality and Business: Exploring Possibilit…—Brian Van der HorstRonnie Lessem and Andrew Schieffer, Integral Economics—Christian […]