Feature Article: Exploring What Is Indian: A Parable and a Discussion

Raghu Ananthanarayanan

Raghu Ananthanarayanan

A Parable:

Raghu Ananthanarayanan

A young woman had committed suicide. She was the daughter of a respected village elder. It was an open secret that this girl was in love with a boy who belonged to a lower caste, but who was educated and lived in the “city.” He held a good job.

The village local Governing Body (Panchayat) sat together to decide what to do. The first decision they made was not to bring the Government process, i.e., the police (“Sarkari law”) into the picture. They then decided that the village elder would be kept out of all the village processes where he had enjoyed a pride of place. A complete social sanction would be applied to him. He would, however, retain his position on all the committees that had an interface with external agencies. In his own home, he was confined to a shed.

As a member of a developmental group that was working with a group of villages, we came to know of this, months after the event. One of the elders explained the situation when we questioned the sudden change in the way the protagonist of our story was being dealt with in the village.

“I am telling you because you are good people and you have been helping us a lot,[1]” he began. “Otherwise, we never share our internal affairs with outsiders[2].” He then described what happened. When we were quizzical about the way the Panchayat had pronounced its judgment, the elder said, “You are people who have understood only the English ways. You will find this difficult.[3] All of us know that the girl was probably driven to suicide. If we go purely by the letter of the law (nithi), we can say the elder is guilty and prove that in the English way. But our tradition is to look at the subjective and culturally accepted idea of fairness (nyaayam).[4] We knew what the girl was doing. All of us have talked about it in our homes. This is a paradox involving painful choices (dharma sankata). The girl has been exposed to the new ways; for her, the traditional ideas of family and caste clash with the new idea. You people are also representing that view. She sees new films where romance is emphasized over duty. The father is the representative of the village tradition. His family is one of the most respected here. Once the romance is over, these two will have to lead their lives amidst their families. In our culture, the marriage is between families.[5] How will the two families relate? What happens to the status of the elder? We have also discussed this at our homes. We have similar confusions. None of us has been able to resolve this Dharma sankata for ourselves. It must have been a very emotional issue for the elder. Does he choose from his personal position and his feelings for his daughter or does he uphold tradition? What does the daughter do? Does she choose from her new ideas or does she respect her father’s turmoil? Overcome by emotion, the father has said things to hurt the girl. She has taken them to heart and lost her mind. The man has to live with his self-accusation that he caused his daughter’s death. What can be worse than that! After all, ‘each person must live with his own inner witness.’[6] No one can know what is right. We have such small brains. ‘What is known will fit ones palm and the unknown is as vast as the earth.’[7] The elder was so caught between his own sense of shame and his wish for his daughter’s happiness, that he became embroiled in his emotions. That’s why we are told, ‘Listen to four people’ before taking a decision.[8] Unless you hear an opposite view from some one you respect, you will always get caught with your opinion.’”

“Why keep him on your committees?’ we persisted. “We have established fairness (nyaaya) by the social sanction. Why bring shame to the whole village? Why loose his knowledge. Even his son will consult the man for important decisions, but he will live in the outhouse, and won’t be invited for any auspicious occasions. Are these not enough punishment? Why destroy him and everyone who will benefit from his presence for one error of judgment? Why are you so worried? The elder stood in front of the Panchayat and accepted the judgment. He will stay within the bounds of his role and our tradition.[9] He might have lost his senses for a short while; he is not a bad person. Lord Rama also had to go through the same dilemma. Did he not send a pregnant Sita to the forest?”[10]

We have shared this story with others who work in the development sector and they vouch for the essential likeness of this story with many of the ways and the struggles of the village people to come to terms with modernity.

The Discussion

Over the years of my search to discover “What is India? And what is Indian?” I have discovered that many Indians struggle with this question. At Sumedhas (www.sumedhas.org), where we explore issues of identity in learning laboratories, we often encounter poignant struggles with the question, “What does it mean to be Indian?” Many of us swing between self-love and self-hate when we search for our roots. Many of us swallow the myth of western discourse that says, “India has great spiritual wisdom, but at the level of pragmatic knowledge it has nothing of value.”

My search has taken me to the villages of Tamil Nadu and Andhra, tribal areas of Maharashtra, holders of the ancient lineage like Krishnamacharya, Desikachar and Ganapati Stapati, researchers like Dharampal and his colleagues from Peoples Patriotic Science and Technology, process workers like Pulin Garg and Gaurango Chattopadhyay, a smattering of spiritual teachers, and people very accomplished in science, technology and business management. As I look back at this long journey, I can only say that I have some sense of what Indian might be. Let me share some of my thoughts on this question.

The anecdote I started with is not extraordinary in anyway. I have heard the mixture of folk wisdom interspersed with traditional sayings on many occasions when having conversations with simple villagers. Why it is extraordinary is that several profound philosophical ideas are reflected in these conversations. Let us examine a few. One of the key tenets of Sankhya is conveyed in three words. “Gati, Samghatana and Niyati” – these words describe the nature of all phenomenon. Gati means constant change, Samghatna means interconnectedness and interdependence of all phenomena, and Niyati means order in the process of change. This idea is explicit in Yoga and in Buddhist thought and is reflected in almost all Indian thought: The transitoriness of all phenomena and the doctrine of dependent origination.

Another idea that is interesting is the description of knowledge. All knowledge is subjective and the final test of truth (pramaana) is pragmatic applicability. This combination of ‘conscience’ and ‘pragmatics’ as the two criteria for determining truth, as well as being the ultimate basis of choice making, is echoed in many areas. In mathematics, the application of an algorithm or a method is accepted as a proof, not abstract reasoning. The valid teacher (aapta vachana) is one who demonstrates high convergence between what he professes and how he lives.

The idea of ‘Dharma Sankata’—the decision-making dilemma—is very central in Indian thought. In fact, the Bhagavad Gita starts with Arjuna’s explication of his Dharma Sankata. (A recent book written by Guruchran Das, The Difficulty Of Being Good, focuses entirely on this aspect of the Mahabharatha) A Dharma Sankata is a choice-making situation where two or more equally valid options (with equally positive or negative consequences) confront a person. Not only does the person have to question the veracity of his own perceptions and conclusions, he has to bring himself into the situation, discover his conviction and value stance, and take a decision. Since one is always limited in ones capacity to know, these decisions are taken within the ‘partial, inadequate knowledge’ (Avidya) available now. Therefore, ‘Nyaaya’ is more valued than ‘Nithi”. Nithi is law as it is written down, and the basis of so-called objective judgment. ‘Nyaaya’ is a subjective choice of ‘fairness’ in action that restores a balance. Nyaaya sees truth as relative and determined by the context; it rejects the idea of a changeless objective truth that can be established by human thought especially in matters of value judgments. In mathematics the use of ‘syaad vaad’ (provisional truth-value) is particularly of interest. This principle says that knowledge is limited, and any postulation of truth simultaneously creates four possible statements—its opposite, neither the postulation, nor its opposite; both the postulation and its opposite, i.e., four possible ‘truth values’.

If we now go back to the conversation with the ‘simple’ villager, we find many of these profound ideas reflected in his statement. The primacy of ‘Nyaaya’ (subjective fairness) over ‘Nithi’ (objective judgment), acceptance of the subjective reality and therefore a socially acceptable ‘punishment’, the primacy of conscience, the importance of the ‘whole’ where the punishment of the ‘part’ is not seen in isolation of a web of relationships and dependencies, balance as a central principle, acceptance of one’s limitations of knowing, the criticality of the dharma sankata in decision making not only of the errant elder, but of everyone in the community, a refusal to ‘objectify’ the person, and an ability not to look at a transitory state of mind as the entire description of the person. The struggle between living the continuity of a tradition and coping with the power of a foreign set of ways underlies the conversation. It is seen as an ‘un-official discourse’ that can be had only with a friend. This way of thought, feeling, and action is shrouded and protected from the official glare through a cloak of silence.

I am aware that ‘India’, the cultural entity, has many facets and parts. While the agrarian village is a huge presence, we have tribes, warrior races, traders, artisans, artistes, and wisdom carriers who are all part of the tradition. My submission here is that some of the parallels I have tried to show in this paper are important elements of “What is Indian?” and that they run through almost all Indians as a quiet background, whether it be the simple or exalted person. The arrested development of the traditional and its uneasy confrontation of the modern is also part of this background as noise. Let me illustrate with a few examples.

I was facilitating a strategy session with a division of a Multinational pharmaceutical corporation. I first conducted a session where people shed their roles and interacted as human beings. They asked very simple questions of each other and narrated stories (through a process called micro labs). This was the first time people who had worked together for more than a decade (and had been to many official parties) had shed their facades and interacted as people.

I explained that the traditional design of an Indian town had a space dedicated to a meeting of people shorn of all roles and hierarchy, often accompanied by a narration of stories from the Mahabharatha or the Ramayana. Then, I proposed a conversation between representatives of four voices: The voice of the Shareholder, the voice of the Customer, the voice of the Employee and the voice of Technology. Any one who had a significant contribution to make could move into the space designated for each voice and say his/her piece.

As we went through the process, the head of the unit became agitated at first but after a while, he joined in with gusto. At the end of the day, he spoke to the group in a very emotional voice. He came from a village; he was the first person in his family to work in a city. The eldest in his family was always part of the Panchayat. He had seen many consensus decision-making processes in the village. “What you asked us to do today was very much like the Panchayat. I always thought that these processes are not official! I have always seen them as backward.” He went on to talk about himself to a small group of us over a drink and confessed to having always tried hard to hide his roots. He felt inauthentic and fragmented between his private self and his public self, and suffered from a fear that his “village self” would be found out. He always looked for legitimization for ideas that were drawn from his traditional wisdom in management books. “What a lot of resources I have wasted and how much I have distorted myself,” he lamented.

This is not an unusual story. It is all too common even with many traditional business families that run large enterprises in India. A lot of tension is caused between “professionally trained” managers and the family around the deployment of indigenous wisdom.

Let me take you through a great success story, also. The Tamilnadu Water and Sewerage Disposal Board (TWAD) had been given a large grant from the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). The grant had a few conditions like community participation. The main problem though was the apathy of the Department officials. V. Suresh and Pradeep Prabhu were called in as Organization Development consultants to the project. Pradeep and Suresh sought my help to design the intervention.

The problems were huge and complicated by the ever-present issue of corruption. We came up with a design that we called the “Koodam.” A koodam is an integral part of the design of all traditional homes. It is an empty space in the centre of the house where all community events would take place. Celebrations, mourning, collective tasks like drying the grain as well as discussing serious matters that impact all the stakeholders or “pangalis” (literally, all those who shared in the gains and the losses, the joys and sorrows of this family). The critical requirement was that when people gathered in this space, all hierarchy and all differences are set aside.

We took a gamble with the design on the faith that the psychological memory (interesting coincidence, I had typed out mammary and misspelled the word! a Freudian slip if there was any, India has lost touch with its mother goddesses as it runs behind the mammon of GDP) of these institutions of community building is still present in people’s minds. A series of workshops were conducted where we triggered a deeply self-reflective process. These processes were called the koodam. The koodam was a space where the bureaucrats who were part of the Indian Administrative Service and the staff came together as “pangalis”—the shareholders in the joys and sorrows of the organization. They articulated the enlivening practices (Dharma) of TWAD in terms of what an engineer ought to aspire to do. They worked out the plans to design an inclusive process of ensuring water security for the villages of Tamil Nadu. (The entire process is captured in a documentary film by Bala Kailasam, called Neerundu Nilamundu

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v1t1PiRDnc4&feature=&p=284573E677BDB7D5&index=0&playnext=1

and described in a paper “Democratisation of Water Management: “Institutional Transformation leading to a Paradigm Shift-The TWAD Experience” by V. Suresh and Pradip Prabhu). The process triggered a sea change in the way the TWAD engineers went about their tasks and the results are astounding. The UN has recognized this method as the most effective way of ensuring a democratization of the commons.

To us, the most edifying aspect was the energy that was unleashed when the traditional ways of creating a community and arriving at consensus were legitimized. The language used by the group changed (in many ways it resembled the simple villager we met early in the paper). Their ability to manage the traditional bureaucracy while acting from the institutional empowerment was simply amazing.

What were the key words in the language of the TWAD engineers? You guessed it, all the words we encountered in the ‘simple’ villagers narrative: nyaayam, dharma-sankatam, kadami-kanniyam-kattuppadu (duty-ethics-boundaries), dharmam, samudaayam (community) and the central ideas they dialogued were around the roles to be played, the need to go back and respect traditional knowledge, the need to shed hierarchy while dealing with the villagers! They had discovered how to be Indian and to be authentic to their roots while being TWAD engineers!

The hypothesis that I am advancing is, firstly, the average Indian holds a deep divide between his inner processes of meaning making and his relatively more conscious process of choice making. Therefore, his ways of impacting the world are weakened. For example, we can identify a US version of shaping the world of business and technology, as well as a Chinese, a Japanese or a Russian, but we will find it hard to identify an Indian influence (hopefully this is slowly changing). Secondly, the process of creating acceptable theory in most areas of business is held within a western hegemony. The process of creating an Indian theory of the psyche and collective dynamics is therefore held captive to this hegemony. For example, many psychologists starting from Carl Jung have acknowledged their Eastern influences, but reinforced their commitment to revalidate, reformulate the insights in the language and through a process acceptable to the West. In India, we neither seem to take these theories in with a sufficiently rigorous process of study, nor do we go back to our roots and continuity with a commitment to reframe them in a modern and scientific way. Thirdly, the role models for relevant action (relevant= modern and global) are drawn from the West or from people successful in the business domain. For example, Gandhi is not a relevant role model to most young people today, though most modern movements (Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Eco movement) see him as an inspiration.

Let me digress for a moment and put forward some propositions before I present my argument: Each of us has an idea (more or less clearly articulated to ourselves) of how the following statements can be completed: I am… People are… The world is… We also have an idea of: I wish I were… I wish people were… I wish the world would be … This gap between the “as is” and the “as it ought to be” creates a tension within us. We choose to act in different ways depending on the choices we make. For example, as a reader you can choose to articulate better propositions in your mind, but, say to yourself, “I am only a spectator” and therefore not take the tension seriously. You could say, “I am evoked enough to join in; let me team up with the author and see what we can do.” Or you can be triggered into saying, “This needs a much more in-depth study and analysis; let me explore the field.” In each case, the actions you choose is a “role” that you choose to play in the world. The “role” that you choose contains an energy and a direction. It is a measure of your commitment to your self and to the context. When the inner processes of making meaning are coherent and convergent with the choice of roles and modes of action there is power. Where this is absent, there is internal friction and a loss of power.

My argument is that the average Indian suffers from an internal fragmentation between his meaning making processes and his “role” playing process. He lacks the legitimacy to question the forces and the processes that create this split; he may not even be clearly aware of this. Legitimizing the search for an authentic way and legitimizing the search for role models from our tradition (recent and ancient) is essential if India must unleash the potential and genius of the Indian mind in the Indian milieu and context. The average Indian holds his/her self “as is” in ambivalence, he/she resolves this either by giving in to self-hate or self-aggrandizement. A modern and pragmatic narrative of what it means to be Indian has to be fostered.

Advancing a Framework

I first encountered the profound effects of the fragmentation in the Indian manager when I was conducting a series of week long “Stress Management Programmes” at ITC Limited in the early 80’s. Along with sessions on Aasana and Praanayaama practice, we designed 3-hour sessions on various medical approaches to stress as well as 3-hour sessions on the subjective stressors (every day for 5 days). It was in these sessions that the struggle that the managers experienced between their “Indian upbringing” and their “Western work world” became clear. The framework that follows was used by me in these programmes to help the managers understand the fragmentation and to affirm and legitimize their deploying their “Indianness” in the work space.

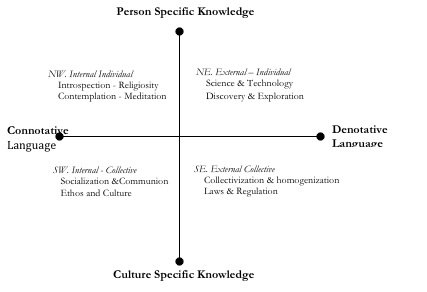

Two types of knowledge are created when we experience the world around us and introspect upon the experience and interpret it. Firstly, there is knowledge that is personal and held with and within the individual. This knowledge in the external context takes the form of understanding how to use tools, how to manipulate language and numbers, how to solve problems and the like. In the context of our inner world, we learn how to manipulate the inner faculties. The assumptions and conclusions that we arrive at take the form of meanings we give to ourselves and our world, ways in which we manage feelings and make choices and so on. Secondly, our experience of the world also generates knowledge that is held in a group context and is deployed by groups. In the external context, this takes the form of social norms, laws and conventions of the group, ways in which shared resources will be used and distributed and so on. In the internal context, this takes the form of the style and modes of relating with others and reaffirming our belonging to the group. This can be called the cultural dimensions of the group. This includes its myths and hero stories, its particular use of colour, form and sound to create beauty.

The knowledge that points to the outer world is coded in denotative language. One can show objects or tangible behaviours that correspond to the word or the expression used. The inner world on the other hand is coded in connotative language. The meanings derived from words and expressions are subjective. Therefore, they cannot be pointed to and verified like the knowledge of the external world.

If we juxtapose these two polarities, we get four orientations to the world.

If we place this understanding in a conceptual map, it looks like this:

The Key Words for Each Quadrant: [11]

Quadrant NE/UR: Object world, concrete, tangible, measurable, yields knowledge through scientific observation and experimentation; adventure, conquest, acquisition, power to shape and impact the world of objects. “I think therefore I am”—Descartes, the scientific orientation.

Quadrant NW/UL: Subject world, intangible, implicit, yields knowledge through introspection and contemplation, spiritual quest, self-mastery, power to understand and manage one’s self. “The tangible, the intangible, the seer all three understood with discrimination is the way out of sorrow”—Sankhya Karika, the contemplative orientation.

Quadrant SW/LL: Shared world of myths and meaning has modes of expression, criterion for membership, yields knowledge through discussion and acceptance, belonging, evocation, urge to express and be received, expression of ones artistic abilities, power to evoke and mould group sensibilities and shared meanings. “Mythology is the language of the unconscious and the path to the unconscious”—Joseph Campbell, the cultural orientation.

Quadrant SE/LR: Control of shared resources, ensuring security in collective living, systems that ensure equity and fairness in the distribution of resources, learning through internalising boundaries and norms, power to direct collective action. “By all according to the capability and to all according to the need”—Karl Marx, the political orientation.

Civilizational Preferences

All the quadrants are essential for life. However, individuals will have a greater propensity or facility with one or more. From the perspective of human history, it would seem that each quadrant speaks of a type of civilization and the way their particular world has been shaped by its people in the course of time. To me, Europe epitomises the NE/UR quadrant. The Cartesian statement, “I think therefore I am,” captures the essence of the location. Europe has since the Renaissance clearly separated the scientific and the technological from the religious. The technological has taken greater and greater space in the minds and hearts of people over the years. Organisations that exploit technology took root in Europe. The laws governing individual ownership of land and property came from England, as did the first joint stock company. Colonising other nations for the purpose of exploiting their wealth was most successfully accomplished by Roman and Mongol empires. India, too, was a great coloniser, but it focused on spreading a cultural and spiritual message.

The Indian subcontinent epitomises the NW/UL quadrant. The Vedic affirmation, “I am Brahman,” is its quintessential statement. India has constantly referred back to a spiritual, religious legitimacy for all its expressions. Every scientific treatise (and we have many of them in various branches of science and mathematics) locates itself in some spiritual tradition and binds the use of the technology through religious injunction. Its cultural forms of celebration, for example, are intertwined with spiritual mythology. Its social laws and norms, its socio-economic structure, is embedded in religious rhetoric.

China and Japan represent the SW/LL quadrant. The idea of the “Cultural Revolution” symbolises this location. The manner in which China and Japan dealt with the Western world illustrates their ways. While both of them sealed off the nation from the invaders, they opened out one or two parts selectively to specific nations. A few families were allowed to follow the ways of the aliens. Learning percolated to the rest of the nation through this process. The centrality of collective ways of acting and the belonging to the collective were emphasised and reinforced through dramatic and cultural events. The collective being an important anchor of individual identity comes through in many ways. Japan is referred to as Japan Inc. because of this mode of being.

The communist experiments of USSR and Eastern Europe illustrate the SE/LR quadrant located civilisation. “To each according to his need and from each according to his ability” is its quintessential statement. State ownership of all means of production and mandated absence of multiple forms of political thought are examples of the processes that belong to a SE/LR quadrant location. The struggles of the communist block post “Perestroika and glasnost” also illustrate the dysfunctional imposition and forced conformity to the SE/LR quadrant process.

Any nation, group, or organisation that hopes to grow in a healthy manner must have a balance and harmony among the four processes described so far. Unfortunately, this has not been the case. While Europe has located itself clearly in NE/UR quadrant, India has located itself in NW/UL quadrant. The dysfunctional fallout of a skewed process relying overly in any one quadrant is evident in every civilization when one looks deeply into it. The dismantling of the distortions of exclusive SE/LR quadrant processes in the erstwhile USSR has led not only to Balkanisation, but also huge disparities in social structure, deep erosion of values and morals, in short, a deep rupture in the fabric of living. The dysfunctionalities of Europe are illustrated through the World Wars, the idea of “conquest of nature through science,” etc. While the Indian location sounds mystic and esoteric, it has its own set of deep-rooted illnesses. The intermingling of the religio-cultural and the socio-cultural has led to the rigidity of the caste system. The violence unleashed by powerful parochial and patricentric governance sanctified by pseudo religious sanction rises like a many-headed dragon in the caste-based politics that is rampant today. The Gandhian way of non-violent Satyagraha evoked the most profound movement in our culture; the same processes devoid of meaning and mission, in the form of dharna (non-cooperation) and protest, has led to stagnation and decay. The blatant misuse of traditional respect and trust given to hierarchy is another aspect of this dysfunctionality.

The fact that India was colonised has added to the fragmentation and dysfunctionality of the polity as we experience it today. There seems to have been a natural balance between the four quadrants that existed in the reign of Ashoka and until about the 10th century. There is a continuity of debate and review in the philosophical schools. Social structures were redesigned and various branches of mathematics, sciences and technology advanced. The Muslim invasions that occurred around this time slowed down and stopped the growth of many of these fields. For a brief period after the reign of Akbar, a balance and dialogue was being explored between the Muslim ways and the indigenous ways. This was a period of growth in many fields, and it ended with the ascension of Aurangazeb to the throne.

Soon after this, the British colonization followed. During these periods, an extreme conservatism took over. Social structures became rigid, and change from within was not encouraged. A strange practice of accommodation, adjustment and assimilation has come to characterise the Indian mind. But many of the older practices continue to inform the familial modes today and therefore become the ways children are brought up. Thus, the NW/UL quadrant world-view is internalised. When the child goes to school and college, the mode changes to a western scientific outlook (NE/UR). This meeting of modes within the person is an uneasy relationship, never quite resolved. The tension between the ‘Indian’ and ‘Western’ leads to an inner waste, and in some cases shame of being Indian. However, where this relationship is resolved in a positive way, huge potential is unleashed.

Leadership and Role Shaping

In this canvas of the world, individuals and groups are often acting on a script that is a product of their world. One often acts within conditioned modes without an inkling of their dysfunctional nature. The unconscious choice making processes that each of us is a part of is mired within these contexts and based on which quadrant our context stems from. We are also products of the internalisations and introjects of our quadrants. Thus, while we feel that our action choice is based on our reason, we are often unaware of the deep coding that is part of our decision-making processes. In the context of managerial role taking and Leadership, it becomes very important that the cultural influences are initially acknowledged and then worked with. The more one is able to balance all four propensities in ones meaning making, choice making and role taking processes, the more intelligent and impactful ones actions will be. At a very broad level, the ways in which we are brought up in India are strongly based on the connotative while we work in organisations designed on the denotative. The disconnect and the stresses that this creates is often managed by the individual at great cost to him/herself.

The Present Struggles

Today India is poised on an exciting threshold. It is flexing its business muscle in the global arena, facing a tense debate between the indigenous ways and the modern ways, discovering resources in its hinterland, and facing a resistance from the tribal groups whose homeland is being intruded upon. The struggle between Orange and Green activists is probably visible globally. The global footprint that some of the large industrial houses in India like the TATA’s and the Mittals are acquiring is very much in the news. This process is creating internal stresses between the educated middle class and the agrarian classes. The insatiable search for resources and their discovery in the tribal belt of India is creating to what some activists like Arundathi Roy call “a colonization of the tribal belt of India by its middle class”. Many small pockets of enlightened Green groups are sprinkled all over the country. Vandana Shiva and Bablu Gangully have been leaders in this area. The other drama being played out is in the social space. The traditional Blue is breaking up and in its place we find a peculiar regression into a ‘consumerist and modernizing’ Red jostling for space with atavistic religious fundamentalism (the Red face of Blue gone awry). The political arena is a slugfest between the parties like the Congress that have an Orange centre of gravity, and Bharathiya Janatha Party with an equally Orange but more blatantly religious right ideology. A plethora of regional parties that I can only describe as “Purple-Blue with Red polka dots” align and re-align themselves with these two till one does not quite know who is on whose side and how the policies of one differs from the other. Meanwhile, we have real and pseudo spiritual leaders singing their song.

Epilogue

If we now turn back to look at the parable we started with, one will be able to see the contemporary contours of the civilizational threshold that faces India. The deep layer of feeling of most Indians has the colours of the NW/UL quadrant, whether it is a villager or an urban citizen. The villager has found ways of managing the split that the confrontation with the westernized forms of SE/LR governance modes by living in two spaces. He names them differently, and identifies them by a language-based definition. For example “angrezi likho” (write it in English) is a euphemism for bureaucratic processes or legalise. Prof. Amarhthya Sen’s in his writings discusses the idea of “Nithi” (Justice as dispensed with in courts of law) and “Nyaya” a sense of fairness and balance. “Nithi” happens in English and “Nyaya” in vernacular!

The urban western educated Indian however has to struggle with this split in ways that fragment him in subtle ways. Frantz Fanon’s classic exploration of this split in the colonized African people (Black Face White Mask; Paris du Seuil; English translator Charles L Markmann 1967) can easily be situated in India. Ashish Nandy has explored this in the Indian context in his book The Intimate Enemy, Loss and Recovery of Self Under Colonization (Oxford University Press 1983). India has made cricket its new religion and become the number one nation in the sport that was once the preserve of the British coloniser (Ashish Nandy has commented about this too in his book The TAO Of Cricket, On Games Of Destiny And The Destiny Of Games OUP). May be we will succeed in assimilating and digesting modernity some day, may be we will struggle with the spilt for a long time to come to terms both within ourselves and in our external ways.

Which colour from the SD frame do you want to see? I will show you the most functional and the most dysfunctional forms of it in this country that I love, a country that continues to baffle me.

I must seek your indulgence in presenting to you my formulation of this framework. I came upon the framework independently, and I have used it for many years to understand and explain the way in which different cultural influences have impacted India and then taken root as India developed. Every civilisation has expressed itself in all four quadrants. However, there are distinct differences that have come out of the cultural locations they have chosen for themselves. The reasons are many and probably embedded in the geography and the history of each civilisation. However, when an old civilization is impacted by the processes and meanings that are anchored in the colonizing civilization (with an idea of man and the world very different from the colonized), stresses are developed at a very deep level between the colonized individuals’ Identity processes and the action world. I have used the framework to look at these stresses in an organisational context.

Notes

[1] Neenga nalla manas vechirukkenga, nalladu cheiya virumbareenga, athanala chollaren

[2] ull vishayattha veliyile cholla mattom

[3] neenga cheemai padippu padiccavanga

[4] Nithi murai vera madiri, nyaaya vazi vera madiri

[5] Kaadal mudinja piragu kudumbam thane thangikkum

[6] Kadeichiyila nammaloda manasatchiyodu vazanammilla

[7] Kattradu Kai mannalavu, Kalladadu ulagalvunnu cholluvangalla

[8] nalu perukitta ketkannumnu cholluvanga

[9] Kadami, Kanniyam Kattuppadu thandamattan

[10] Raman enna valzndan? Garbhini sitavalla kattukku anupinan

[11] The reader will no doubt recognise the AQAL framework of Ken Wilber. I first encountered Ken Wilber’s work through Prasad Kaipa in the late-eighties. I have since then become a fan of his work.

About the Author

Raghu Ananthanarayanan is a Trained Behavioural Scientist, Yoga Teacher and an Engineer; Founder of the consulting firm “FLAME TAO Knoware”—a team of functional experts all of whom are Behavioural Scientists focusing on Organisational Transformation, Alignment and Optimisation; and Chairperson Sumedhas Academy for Human Context—a not for profit organization focusing on developing behavioural scientists. His consulting experience spans three decades: organization turnarounds, leadership coaching, culture transformations. His clients include TCS, Infosys, Claris Life Sciences, Laxmi Machine Works, ITC, and EPCOS. He pioneered the use of Yoga and Theatre in process work. He has published many papers and two books: Learning through Yoga and The Totally Aligned Organization. His goal is to develop a unique approach to management at a personal level and at an organizational level based on the three streams of his expertise namely, Lean Management, Yoga and Behavioural Sciences. He has already developed many models and frameworks, as well as practices, some of which are being converted into a software product and others into a set of video-based leaning modules. He can be contacted at raghu@totallyalignedorganization.com

Profound thought process with clarity of difentiating between “Indian” & Westen thought and way of Managing Context. Legitmacy of being Indian foster selfs integration.

Best article, lots of intersting things to digest. Very informative

[…] Om Prakash Bhatt, Chairman of the Board, State Bank of India – Prasad KaipaFeature Articles: Exploring What Is Indian: A Parable and a Discussion – Raghu Ananthanarayanan The Integral Self System Model and Sustainable Leadership – […]