8/31 – Leadership, Mindflow and the Integral Point of It All: The role of Integral Leadership in bringing mindfulness and flow to the workplace

Ron Cacioppe

Ron Cacioppe

Summary

Summary

This article reviews the definitions, characteristics and research dealing with mindfulness, meditation and flow and their positive effects on individual health, interpersonal relations, workplace engagement and performance improvement. This article explores the role of integral leadership to provide conditions for mindfulness in flow (mindflow) using an integral framework.

There is growing interest in both mindfulness and flow in the workplace, but the role of leadership in developing mindfulness in flow is seldom considered. This article suggests that Integral leadership complements and includes current approaches of leadership, and provides an AQAL framework that is ideally suited to bring mindfulness into flow (mindflow) at the integral point. The role of Integral leadership is to align the four integral worlds to provide the conditions that encourage flow and help individuals, teams and organizations to develop through eight stages of self-identity

For leaders to use this integral approach, they need to understand the integral framework and embody mindfulness in flow in their actions. The leader also needs to act as a model, conductor, coach and guide for individuals and teams to benefit from the mindflow process.

A key and natural function of Integral leaders is to bring mindflow conditions and practices into the workplace to enhance employee wellbeing and satisfaction and improve organizational performance. This article suggests that in addition to these benefits the function of integral leaders is to connect themselves, their staff, teams and organizations with the larger flow of creative emergence, the ‘Great Flow’.

Introduction

Programs in mindfulness and meditation are now common in the community and increasing in the workplace. Many people begin mindfulness and meditation practices to reduce stress, sleep better, deal with conflict and problems or to have some mental quiet in their fast paced, technology driven, busy life.

The testimonies about the benefits of meditation by celebrities such as the Beatles, Oprah Winfrey, Richard Gere, Hugh Jackman and successful business people such as Steve Jobs and Arianna Huffington popularized the idea that meditation and mindfulness as necessary for a fulfilling life. Organizations such as Google and Facebook proudly describe mindfulness and meditation practice as part of their workplace (Shachtman, 2013).

A study by Killingsworth and Gilbert (2010) has shown that for about 47% of our day we are not in the present moment. Almost one half of the time, our minds are wandering to somewhere else. When we are not present, productivity suffers since we are less efficient and make mistakes because we don’t see what is in front of us. According to Killingsworth and Gilbert’s research, when the mind wanders we experience greater moments of unhappiness because it drifts to personal concerns and worries.

Killingsworth and Gilbert also found that the greatest moments of happiness occur when we are in the present and immersed in the task—in flow. During these times of being fully in the moment, we experience a state of complete contentment.

Many of the characteristics and qualities of flow are similar to mindfulness, yet little has been written or researched regarding the relationship of mindfulness to flow and if mindfulness and flow together can enhance individual and organization performance and development. Also, while mindful leadership has gained interest, few dots have been connected regarding the role of leadership in connecting mindfulness and flow in the workplace.

This article clarifies the similarities and differences between mindfulness, meditation and flow and suggests that integral leadership can play an important role in developing a state of mindfulness in flow which has considerable benefit for modern organizations.

Mindfulness and Meditation: Research and Benefits for the Workplace

If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear as it is, infinite.

For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.

William Blake

According to Kabat-Zinn (1990) and Williams and Penman (2013), mindfulness is a state of enhanced attention to and awareness of present experience in an open, relaxed, non-judgmental way. Mindfulness practices include letting go of biases, frustrations, pre-conceptions and judgments of others and negative emotions and expectations. Wilber (2016) has described levels of mindfulness, with the highest level involving the loss of ego self. Wilber calls this process, ‘Waking Up’.

Mindfulness has its roots in meditative, spiritual traditions, where conscious attention and awareness are actively developed. The state of non-judgmental awareness is considered sati, or mindfulness—to see things as they really are.

Meditation is often taught as a key part of mindfulness training, which involves setting aside time to quiet the mind, where the mind focuses on one thing such as a word, image, or the breath, and brings the attention back to the object of meditation when thoughts, emotions and distractions occur. It may also include elements of managing negative self-talk and beliefs to help return to the present moment.

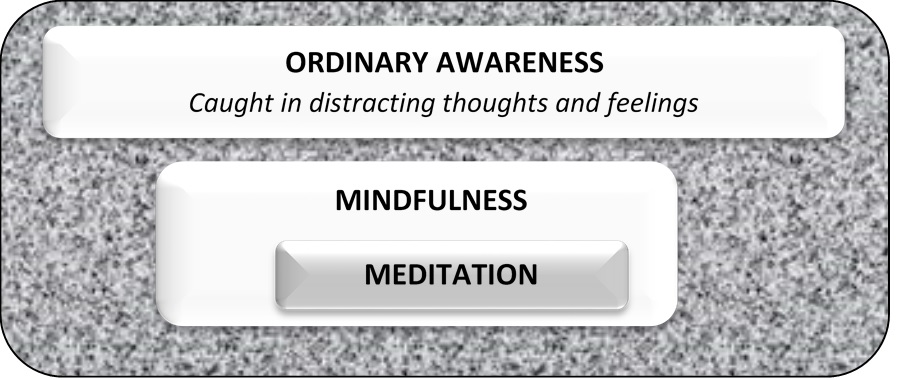

As the diagram below shows, meditation is a specific form of mindfulness.

Diagram 1: Ordinary awareness vs mindfulness and meditation

Meditation, like mindfulness, includes being aware of what arises (sounds, feelings, emotions) but also aims to attain a deep level of stillness, to experience the ‘ground of consciousness’ (Reninger, 2014, Tolle, 2003). Mindfulness is practiced in everyday activities such as walking, eating, driving and working, while during meditation, participants focus on an object of meditation, usually in a seated position.

During both mindfulness and meditation, a person experiences physical, mental-emotional relaxation, slowing of time, a feeling of freedom and boundlessness and, in certain states, a loss of self-consciousness.

Research on mindfulness and meditation took a leap forward with the introduction of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) which shows that new neural pathways can grow and even change the size and structure of the brain (called neuroplasticity). Mindfulness training has been shown to increase activation in parts of the prefrontal cortex where much higher-order thinking, judgment, decision-making and planning occur. Studies showed that in long term meditators, the cortical regions associated with process sensory input were thicker and that meditation increased brain activities involved with learning and memory processes, emotional regulation, self-reflection and perceptiveness.

This technology helped explain how mindfulness can lead to a range of health benefits. Two meta-studies summarised the results of several years of meditation and mindfulness research: “What are the Benefits of Mindfulness?” (Davis and Hayes, 2012) and “Brief Summary of Mindfulness Research” (Flaxman and Flook, 2012). Among the health and social benefits they summarised are lower blood pressure, reduced stress, less heart disease, reduced recurrence of cancer, fewer headaches, better sleep, slowing of the aging process and bolstering the immune system. Recent research shows that meditation can lengthens the telomeres in chromosomes which helps overcome the negative effects of stress and aging (Blackburn & Epel, 2017). Social benefits include improved interpersonal interactions such as trust, self-esteem, life satisfaction, reduced alcohol and drug abuse, and less crime.

Reb and Choi (2014) identify a growing interest in mindfulness in organizations and provide a summary of evidence that mindfulness results in improved job satisfaction, reduced employee turnover and absenteeism, improved workplace learning and better situational awareness.

An eight-week meditation program that taught meditation to 178 workers showed significant reduction in the meditating group on measures of strain and depression (Manocha et al, 2011). Davidson and Kabat-Zinn (2003) taught mindfulness meditation to workers over eight weeks and reported increased happiness, energy and engagement, and decreased anxiety. They also showed that activity in the left prefrontal cortex had increased, confirming a physiological change.

Nurses reported greater relaxation, self-care and improvement in work and family relations after meditation training (Shapiro et al, 1998). Kirk et al (2011) found expert meditators were twice as likely to make economically rational decisions and reduce negative emotional responses compared to a control group. The ability to learn, improve memory, achieve faster reaction times, and increase mental and physical stamina and performance in school was improved through the regular practice of meditation (Reb & Choi, 2014).

Ray et al (2011) see the introduction of organizational mindfulness has value for managers to help them respond to a changing and challenging environment.

In summary, meditation and mindfulness, has resulted in considerable benefits for personal health and wellbeing and more recently, for the workplace in performance, learning, engagement and job satisfaction. These benefits are confirmed by physiological improvements in brain, heart, and blood cell functioning.

Flow: the optimal experience

Flow, as a state of consciousness, has been described and researched by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Professor of Psychology and Management at Claremont Graduate University (1990). Csikszentmihalyi defines flow as “the mental state of operation in which a person performing an activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energised focus, full involvement, and enjoyment in the activity.” He describes flow as the optimal human experience.

Csikszentmihalyi’s studies have clarified characteristics of the flow state and conditions that help bring it about. He describes the following nine components:

- A balance of challenging activity and skill

- Merging of action and awareness

- Concentration on the task at hand

- Loss of self-consciousness, a sense of a separate self disappears

- Altering of time, including time standing still

- A clear, purposeful goal

- Unambiguous feedback

- A sense of both control and spontaneity

- Autotelic experience: the activity has no purpose other than itself

Ginny Whitelaw, Zen teacher and author of The Zen Leader (2012), describes this state: “Doing work we enjoy, we may slip into a sort of ‘work samadhi’ or flow state; when we lose ourselves in the task, time disappears and we only recognize we’ve been in this state once we leave it. Any concerns for self seemingly disappear.”

Phil Jackson(1995), ex-basketball coach of the Chicago Bulls and LA Lakers and winner of six national basketball championships, describes the flow state: “All of us have had flashes of this sense of oneness—making love, creating a work of art—when we’re completely immersed in the moment, inseparable from what we’re doing. This kind of experience happens all the time on the basketball floor; that’s why the game is so intoxicating. But if you’re really paying attention, it can also occur while you’re performing the most mundane tasks.”

Research and benefits of flow

According to an international Gallup survey, between 15% and 20% of adults claim to experience flow every day. Another 60% report being intensely involved in what they do anywhere from once every few months to at least once a week (Csikzentmihalyi, 2004). Studies confirm flow is a universal state across different activities such as elite and non-elite sport, aesthetic experiences, literary and scholarly writing, creative and social activities and in a wide range of work activities.

Research studies have shown the greater time a person spends in flow, the greater self-esteem they experience (Wells, 1988). Several studies have linked flow to commitment and achievement during high school (Carli, et al, 1988). In studies of two university courses, flow predicted semester end performance (Engeser, et al, 2005).

Research (Kee & Wang, 2008) into the relationship between mindfulness and flow in student athletes found that athletes grouped together in a high mindfulness cluster scored significantly higher in the flow components of challenge-skill balance, clear goals, concentration, control over their actions, and loss of self-consciousness as compared to athletes grouped in a low mindfulness cluster.

An investigation into the dynamics of flow in the workplace found that employees experiencing high levels of flow were more flexible and adaptable in the workplace and more likely to seek opportunities for action (Ceja & Navarro, 2011). They also discovered that high levels of flow occurred during healthy dynamic of chaos in the work environment. A study by Fulgar and Kelloway (2009) showed a significant positive relationship between flow experience and positive mood, and that tasks requiring complex skill, expressing creativity and resolving problems lead to a more frequent experience of flow.

Studies have found that the flow experience has a direct positive impact on job satisfaction, performance, engagement and motivation (Chui & Lee, 2012, Lee, 2004, Bryce & Hayworth, 2002, Bason & Frane, 2004). The Swedish-owned company, Green Cargo, moved from a long history of losing money to a profitable company in 2004, one year after introducing new work practices based on flow principles (Ceja & Navarro, 2017)).

Paradoxically, while people experience flow more often at work, they rate the experience less enjoyable then other times, possibly due to the negative biases modern, western cultures have of work.

In summary, flow also contributes to improvements in a range of factors associated with activities in the workplace, especially in performance, motivation and engagement. While flow and mindfulness have similarities, they have some different characteristics in the conditions that bring them about and in their outcomes. Flow involves full physical, mental-emotional engagement in an activity while mindfulness is a more passive, observing process.

Achieving the Flow State

Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2009) state that there are two ways to bring about flow. The first is to structure activities and external environments to foster flow and includes leaders setting challenging tasks to match people’s skills, providing clear feedback, having suitable work spaces and sufficient resources, building efficient processes and effective systems, and empowering staff to make decisions.

The second way is to assist individuals in finding flow for themselves. This involves individuals setting their own challenges. developing skills to meet these challenge, setting themselves goals, focussing on the task, setting aside sufficient time and monitoring their emotional states (Marelisa, 2017).

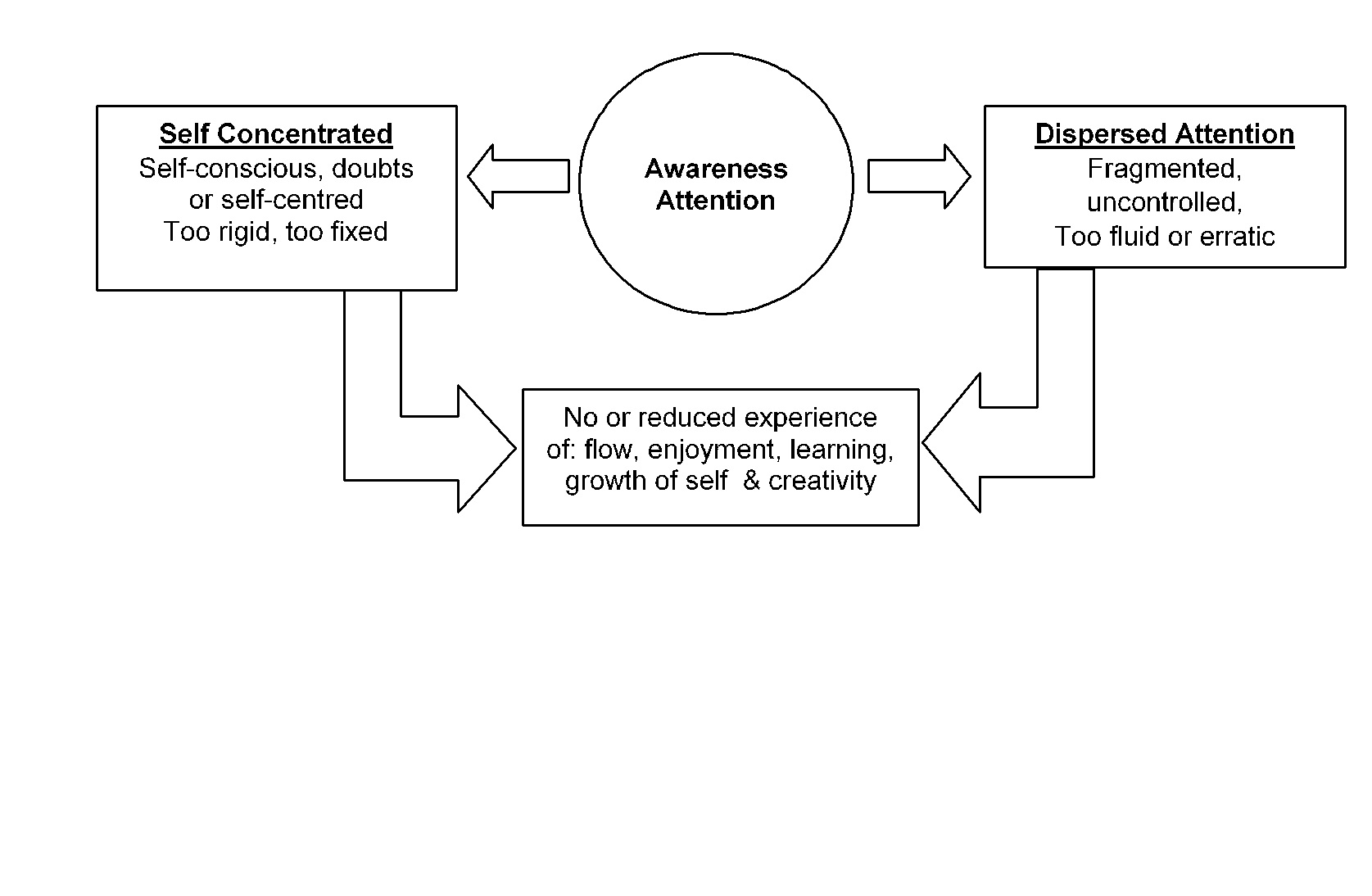

Csikszentmihalyi (1990), however, indicates that some individuals have tendencies that make them less capable of experiencing flow because of their inability to manage their attention. Some people are unable to hold attention on one thing because their attention is dispersed and fragmented by external stimuli which inhibits entering the flow state.

Another inhibition in controlling attention is excessive concentration on self. One type of self concentration is the tendency to constantly worry about others’ judgements, or fear of hurting a person’s feelings which results in a state of continual doubt and uncertainty. Another type of self concentration occurs when a person is excessively self-centred and evaluates everything in terms of how it relates to their desires and self-interest. Both a self-conscious and a self-interested person lack sufficient control of their psychic energy to easily enter flow.

The diagram below summarises the attention patterns that hinder experiencing the flow state:

Diagram 2: Types of attention that hinder the experience of flow

In addition to providing workplace conditions and individual skills, mindfulness training which involves the control of attention away from external distractions and personal self-interest and concerns and worries, would be a valuable way to enhance flow in the workplace.

Mindfulness vs absorption in flow

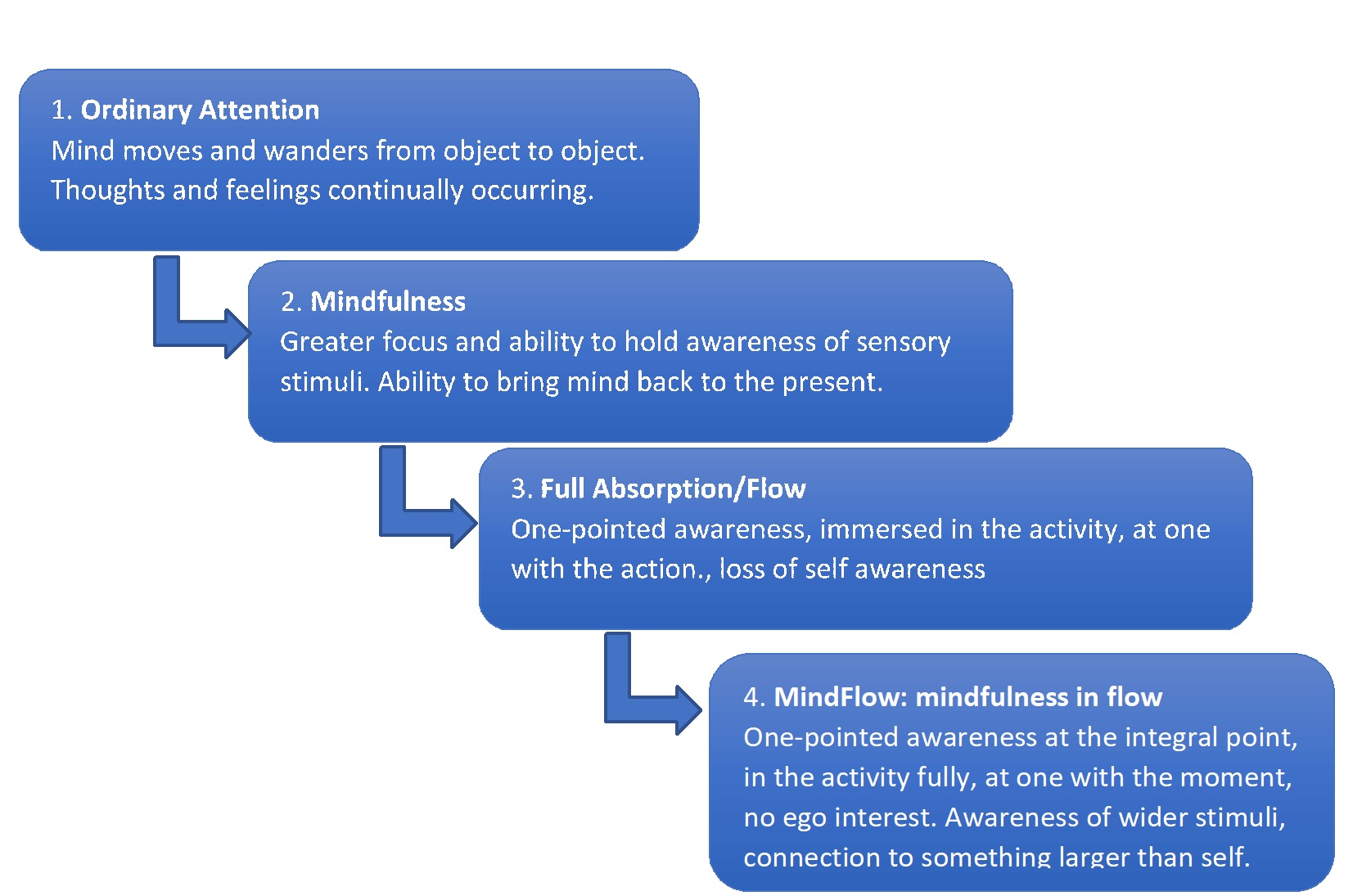

It is useful to examine the differences between mindfulness and flow more closely before considering the role of leadership in mindfulness and flow. The following diagram shows four types of attention, of which the first two, ordinary attention and mindfulness, have been discussed earlier.

Diagram 3: Different Attention in Mindfulness, Absorbed Flow and Mindflow

The third type, full absorption, occurs when a person is in a limited state of mindfulness because their attention is narrow and fully immersed in the activity. Absorption describes a state where the individual is completely attentive to and engaged with their present activity (Rothbard, 2001). In a state of absorption, unlike mindfulness, individuals block out inputs that are not central to the activity.

The absorbed state is different from mindfulness where a person remains aware of the wider environment. Instead, a person will be unlikely to perceive external sounds, sensations, people or things unrelated to the activity (Csikzentmihayli, 1990, 2004, Dane, 2011). A person walking down a street in a mindfulness state is aware of sounds and sights around him including the feelings and tensions within his body, but he may not be in a state of flow. A person absorbed in flow may miss new information or block out important environmental cues. This type of absorbed flow is sometimes called concentration or tunnel vision. A manager described being so absorbed while working at home, he didn’t see his toddler walk past and out the front door.

Shelden, Prentice and Halusic’s (2015) research found an inverse relationship between the absorption component of flow and mindfulness. Participants who experienced greater flow scored lower on measures of mindful self-awareness. Ability, however, to maintain awareness of the environment while keeping a high level of attention on an activity would be a valuable attribute in the modern workplace.

Mindflow: mindfulness in flow

The fourth type of attention includes the ability to bring mindfulness into the state of flow. This type of flow has been described in spiritual practices such as walking, gardening and calligraphy but also can occur in ordinary activities such as driving a car.

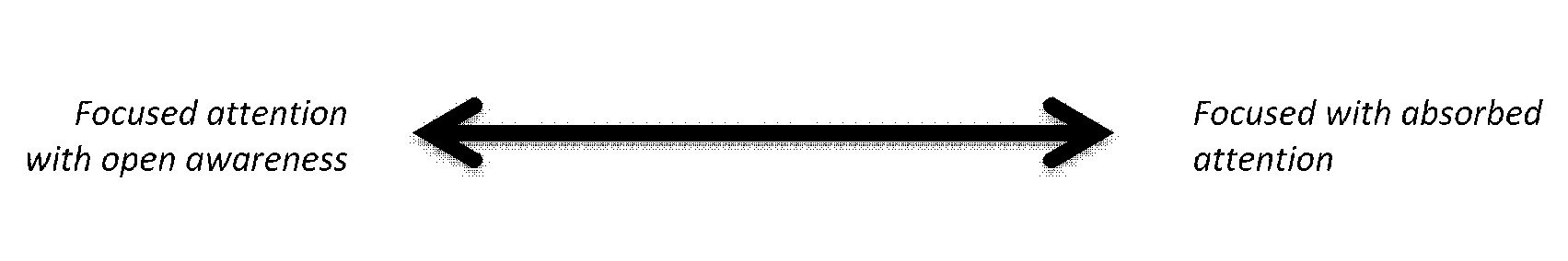

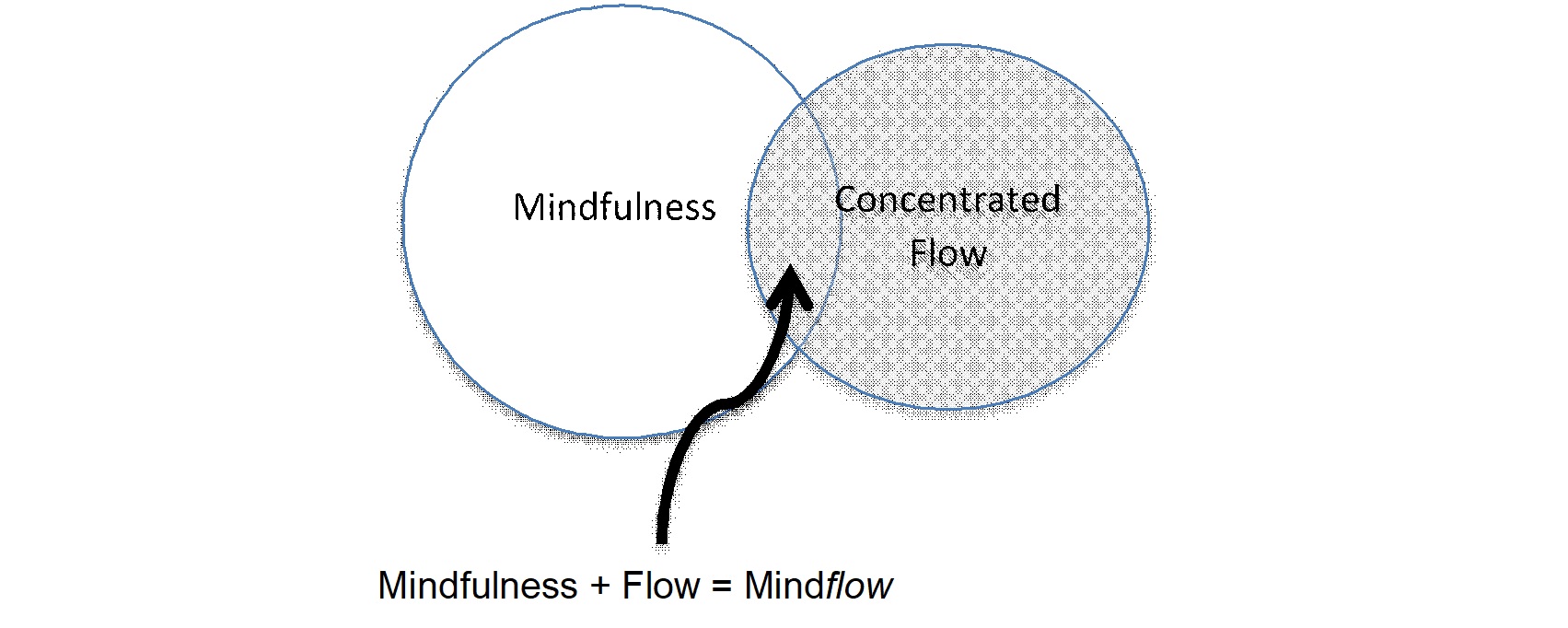

The diagram below shows a continuum of absorbed attention to attention with a main focus yet is open and aware of other information and sensations. The latter is a mindful flow state while the former is a concentrated, absorbed flow state. Both may result in high performance but are qualitatively different states.

Diagram 4: Mindful flow vs Absorbed Flow

Under times of threat such as a car crash, critical deadlines on a project or in highly competitive sporting moments, the situation may require a person to be in absorbed flow. The self gets absorbed into the moment because there is no extra psychic energy available for wider awareness. In mindful flow, there is a high level of attention on the activity but also awareness of stimuli and people in the environment.

The differences between mindfulness, concentrated flow and mindflow is shown in the following diagram.

Diagram 5: Comparison of Mindfulness, Absorbed Flow and Mindflow

While there is overlap between mindfulness, absorbed flow and mindflow, the state of mindflow has a wider awareness of the environment during the moments of flow. This results in a greater ability to respond, learn and adjust to a changing environment.

Whitelaw (2012) describes this complete state of connectedness as Samadhi. “This connectedness is not an exotic condition, but a natural state that arises when we’re absorbed into our setting”. In mindful flow, because the awareness widens to other elements of the moment, a person is open and responsive to other people and changing circumstances.

While concentration on work activities is commonplace, especially in creative, detailed and high level professional and managerial work, it can result in a narrow, focus on ‘my work’ rather than being aware of others. Leaders of organizations are often concerned about the tendency for individuals and teams to operate in silos and continually encourage teamwork through cooperation with other people in their team and other departments.

The ability to be in the present being aware and responsive other people and relevant factors in the wider environment is a skill that managers would like to have in their staff.

Mindflow at the integral point

A fourth type of flow process described earlier was taught by Russian teacher and mystic, George I. Gurdjieff, in the 1930s, at the Institute of Human Development in Paris where he attracted many students, including writers, artists and educators from all over the world. Gurdjieff used the process of the ‘working surface’ (also referred to as the ‘work surface’) to develop students to a higher level of awareness—past ego-based thoughts and emotions—to a level where they fully experienced the moment and connected to something higher than themselves.

One of the few times the working surface is mentioned is in an Ouspensky Foundation exercise file (2015): “Direct all your attention to the work surface. The work surface is the surface between the instrument you are using and the object you are focused upon, for example the surface between the sandpaper and the window sill or the space between the saw and the beam.” In another reference, Colin Brown (2002) states, “Placing our attention on the working surface was our instruction always. … it always reminds me that there is a working surface somewhere ….”. This Gurdjieff process is still taught in a number of schools started by his students, P.D. Ouspensky and Alphred Orage.

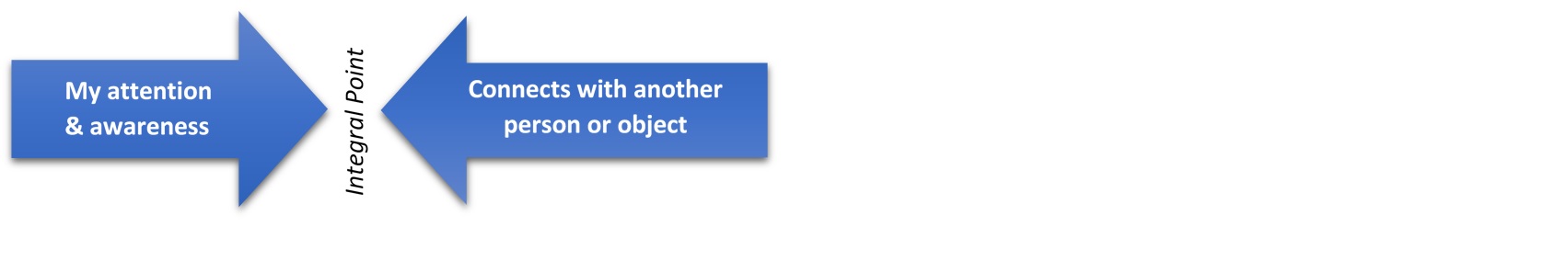

The term ‘integral point’ (integral means to make complete or whole) is used instead of working surface, because it provides a practical and powerful gateway to Ken Wilber’s Integral framework (2016) discussed in the next section.

The integral point is where a person’s attention merges with the outer objective world, the point where the inner world of one person merges with another person or object.

Diagram 6; Attention and awareness at the integral point

The integral point is the central point of awareness in an activity or interchange where connection occurs. Examples of the integral point are:

- When writing or typing, where the tip of the pen touches the paper or the fingers touch the keyboard.

- When driving or riding a bike, where the tires meet the road.

- When playing a sport, where the body touches the ball.

- When listening to another person, the sound of the person’s voice.

- When walking, where the foot touches the ground.

The following is a quote that describes a person’s experience at the integral point: “One Saturday morning I was waxing a floor and was able to keep my attention at the integral point for some time. The grain and colours in the linoleum became so clear it looked like I was watching them on a movie screen. As I worked, the stillness was immense, even though I was aware of the sounds and movements of others working around me. There was no sense of time and, even though I was doing a reasonably strenuous activity, it felt effortless, like I wasn’t doing anything. I felt an overwhelming sense of bliss and gratitude—to be waxing the floor! It was an intense feeling of unity and flow with the whole cosmos. I can still recall the vividness of each of the speckles in the linoleum and that feeling of absolute happiness” (Cacioppe, 2017).

As this quote describes, the experience of the integral point includes the flow characteristics of effortlessness, timelessness, dissolving of self, and vivid experience of the moment. There is also, an awareness of the environment and other people and a connection with something greater than one’s self at that moment.

Jackson (1995) describes this awareness and connection with other players: “The players develop an intuitive feel for how their movements and those of everyone else on the floor are interconnected. Not everyone reaches this point. Some players’ self-centred conditioning is so deeply rooted they can’t make that leap. But for those who can, a subtle shift in consciousness occurs. The beauty of the system is that it allows players to experience another, more powerful form of motivation than ego-gratification.”

The Gurdjieff process has been developed into a four-step process that leads to mindflow: 1) Remember to be present and relax, 2) Become aware of one sense (e.g. breath, listening), 3) Bring attention to the integral point, 4) When the attention wanders, relax and return to awareness and the integral point

Attention at the integral point is a special type of flow that connects with a wider environment, responds to the need of the moment and continually learns and adapts. This process can be used during any activity to bring about the mindflow state but it takes practice to stay at the integral point.

A number of years ago, Scandinavian Airlines market share was dropping along with profitability. Jan Carlzon, as the new CEO, asked all employees to respond to 10,000 ‘moments of truth’ each day when they interacted with the airline’s customers by living up to the airline’s customer promise of excellent service. While not referred to as mindflow, this request, to be present and respond to the need of the customer, turned around the airline’s sales and profit in a very short time.

If leaders could achieve this level of mindfulness, action and clarity of purpose (mindflow) with their employees, it would transform their organization’s effectiveness and employees and leaders would, to use Ken Wilbers’ term, be ‘Showing Up’ authentically and fully.

Integral Leadership; Aligning and conducting Mindflow

Leadership theory, research and practice have progressed considerably over the last fifty years. Leadership was initially considered to be comprised of personality factors such as decisiveness, integrity, charisma etc. and expanded to include situational and contingency factors requiring different styles. Transformational and visionary leadership theory added the elements of a motivating vision and an uplifting moral dimension. More recently the concepts of relational, distributive, authentic and spiritual leadership have been added to leadership theory and research.

Integral leadership provides a comprehensive meta-theory that integrates existing leadership models into an integrated and coherent framework using the Integral AQAL (all quadrants, all levels) which incorporates four quadrants of reality and a development process in which larger purpose and capability unfold.

While integral theory has additional elements (e.g. lines, types, holons, etc), the four quadrants of reality, and stages of development/self-identity, are especially relevant to mindfulness in flow and to the purpose of integral leadership.

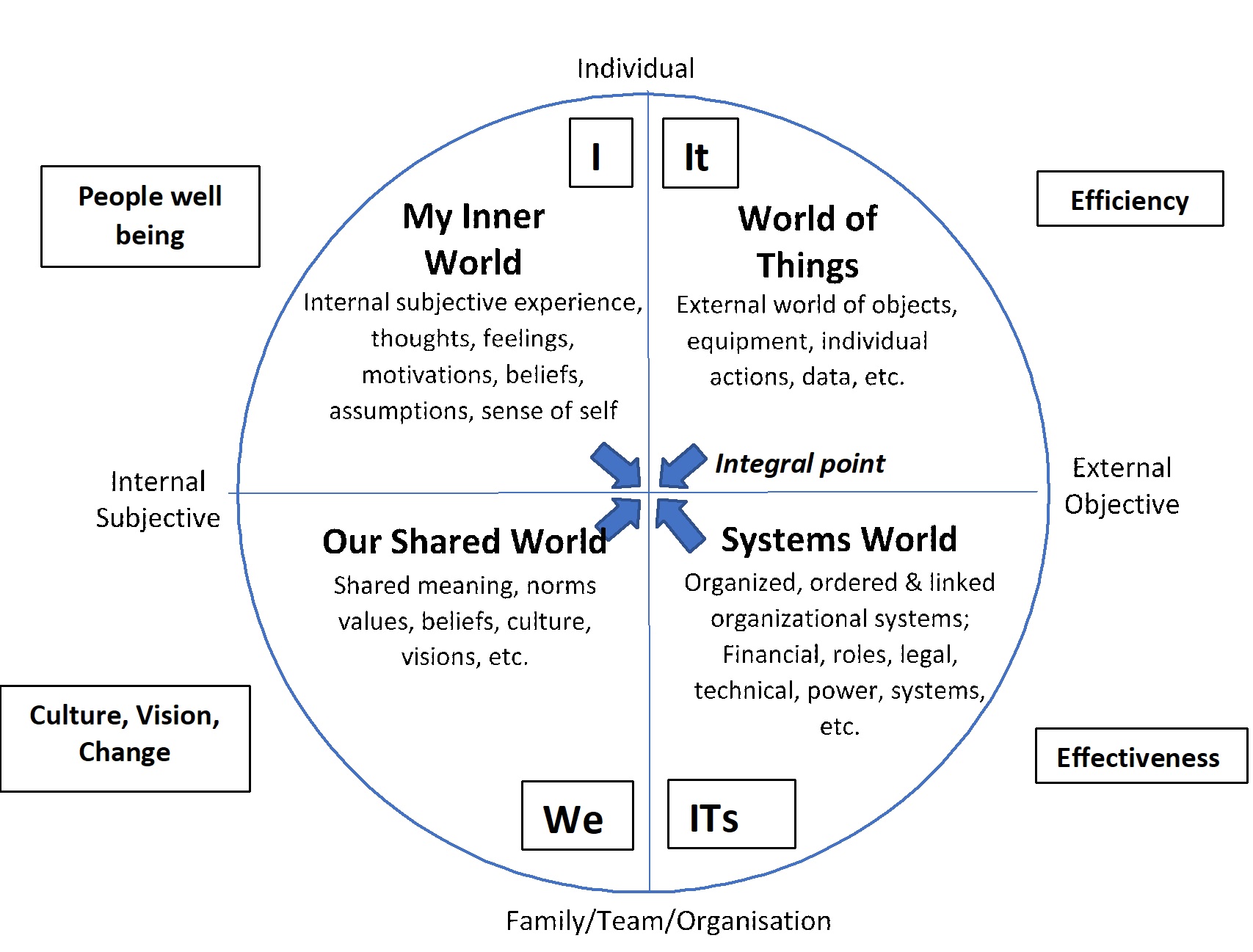

Aligning Four Worlds of Reality to Flow

Leaders deal with continual challenges, dilemmas and paradoxes. For example, they need to keep low costs while providing excellent customer service, they need long term vision and short term results, they have to improve efficiency without sacrificing quality, or build an internal cooperative culture while being a highly competitive company. Wilber description of four quadrants of reality, which he labels as ‘I’, ‘it’, ‘We’ and ‘ITs’ has been used to help leaders understand these apparent contradictory perspectives. In the workplace these areas can be considered four worlds: ‘My Inner World’, ‘Our Shared World’, ‘World of Things’, and ‘Systems World’ and are show in Diagram 7 below.

The upper right of the diagram, is the ‘World of Things’, the outer world of objects is where physical objects and actions exists such as people, tasks, equipment, and resources. All four worlds interact with and influence each other but since we can see, taste, touch, hear and smell things, this world is often described as the ’real world’. In this world, the leader wants to have things done efficiently, to maximize output while minimizing input.

The upper left world, ‘My Inner World, includes the world of personal thoughts, feelings, fears, hopes, values, memory, beliefs and motivation. It includes attitudes, mindset, and personality. People can’t see our inner world but our thoughts and emotions are real. The leader needs to understand and influence staff’s attitude, satisfaction and engagement in this world.

The lower left, ‘Our Shared World’, includes group values, meanings and collective beliefs that form the culture of a team or organization. It is the collective mind of the group that includes its norms, shared stories, myths and unwritten ground rules. Our Shared World’ includes the culture, symbols (i.e. logos, mottos) collective memories and the shared vision of the organization.

The ‘Systems World’ includes systems and structures and links things together into a logical and consistent pattern. The distribution of authority, roles, status, strategic planning, and information and distribution systems are part of this world so determine the control and regulation of work. Leaders use communication, financial, reward and performance management, legal, technical, and political systems to shape the flow of work.

Diagram 7: Four Integral Worlds and the Integral Point

The integral point is where the alignment and integration of these four worlds occur – the point where they meet and the internal, external, individual and collective worlds flow into one.

If the elements in the four worlds are aligned they support and encourage flow but if they are in conflict or misaligned, they inhibit flow. It is hard to be at the integral point when there is interpersonal conflict or people don’t have sufficient skills or resources, or the systems and procedures inhibit effective operations, or the culture is dysfunctional. When elements in the four worlds align at the integral point, flow occurs and results in a balanced organization that performs well and looks after the development and wellbeing of staff.

Different personality types favour one these four worlds. Those familiar with Carl Jung’s psychological types (measured by the MBTI) may recognise these well-researched personality styles (sensing-thinking, sensing feeling, intuitive thinking and Intuitive feeling) that correspond with these four worlds. By understanding the differences in personality types, leaders can understand that problems occur because different types interpret the world differently. Leaders with an understanding of their own and others’ personality type can avoid misunderstandings and conflict by helping balance these four worlds.

A useful way for leaders to understand what factors are contributing or inhibiting flow in the organization is to ask questions which refer to the integral four worlds such as: What things (e.g. equipment, skills, procedures, behaviours, etc.) are contributing or limiting your ability to do your work well? What systems, goals, structures, etc. help or inhibit the flow of your work? How does our culture, values, cooperation of your co-workers and the organization’s vision support or limit you? What are your thoughts, feelings and attitudes about your work (positive and negative)? These questions should be modified to be relevant to each situation.

Stages of Self Identity and Flow of Energy

Stages of self-identity have been defined and researched by western psychologists, sociologists and philosophers such as Abraham Maslow, Jane Loevinger, Lawrance Kohlberg, Ken Wilber, William Torbert, Jenny Wade, and Clare Graves and eastern philosophers such as Sri Aurobindo, G.I. Gurjieff and Buddhist teachings. Some describe these stages based on needs, moral development, cognitive capability or ego development and the number of stages may differ, but their descriptions are strikingly similar.

These stages of self-identity are constructed from our experiences growing up, influences from our parents, friends, school, the media or other environmental factors. They are personal and social constructions that include ideas and feelings about what and who we are.

We put energy into these self-concepts to find our place, to succeed and to attempt to have a satisfying life. We are motivated to do things and put physical, emotional, mental and spiritual energy into maintaining, protecting, and propagating our major identities.

Energy at any stage can become blocked when the self doesn’t have the skills or resources to deal with the challenges and obstacles it faces at that stage. This can result in unhealthy behaviours (known as a ‘shadow self’) such as frustration, anger or criticism.

Understanding and recognising the characteristics, challenges and the unhealthy behaviours that occur at each stage can help leaders resolve problems and develop greater individual and team capability. To do this, the leader must first recognize the characteristics of their own stage of self-identity.

The following are brief descriptions of eight common stages of self-identity and what happens when energy is inhibited at each stage. Colours are used (based on Beck’s Spiral Dynamics) as shorthand for each stage.

The Surviving Self (Beige): In this stage, a person identifies with their physical body and is concerned with survival, safety. security and making enough money to keep things going. The focus of this stage is keep alive and safe.

Energy goes into surviving at all cost – this can mean physical safety or financial security. The signs of unhealthy behaviour in this stage are panic, survival at any cost, short term thinking, and impulsive decision-making.

The Bonding Self (Purple): This stage a person identifies with belonging to a group (e.g. family, sporting team, work group, etc.) which involves maintaining the customs, norms and values that keep the group together. In this stage, a person defines and identifies themselves based on their relationship to the group (e.g. engineer, wife, programmer, father, manager, Eagle fan, etc.).

In this stage, energy is used to connect with others and to maintain and improve important relationships. Energy also goes into actions that help to be liked or accepted as part of a group.

If energy and effort isn’t successful and a person has problems in bonding with members of the group, they can feel hurt, unappreciated and may feel they have failed. They may also feel rejected, embarrassed or not valued by the group.

The Asserting Self (Red): The asserting self-identity wants to stand out, to be important, to make a difference or use force to master a situation. In this stage, power is used to express one’s individuality, uniqueness, influence and role. A person at this stage has a strong desire to breakthrough and come out on top. This may involve taking over or having others conform to their will.

Simple, raw, creative energy is used to get things done without being hindered by group conformity or bureaucracy A person can have courage and confidence in the face of group pressure to overcome irrelevant rules and regulations.

Unhealthy anger, frustration, rage, or a sense of superiority can be displayed when the person gets their will or energy blocked and can’t get their way. Bullying in the workplace is characteristic of this unhealthy behaviour.

The Controlling Self (Blue): In this stage, The self is defined by order, organization and things running efficiently. The person has a strong need for order, perfection, rules, boundaries, responsibilities and a clear hierarchy of authority. It wants clear definition of right and wrong, good and bad and rules of behaviour.

Energy is put into control of others (and one’s self) to ensure everything is perfect or right. If this energy is blocked (e.g. things are messy, done ‘wrong’, standards are not met, etc.) the person can become irritable, bossy, judgmental, critical and even feel guilty for not being able to control things.

The Achieving Self (Orange): In this stage, a person defines themselves by what tehy have achieved. Reward and recognition for accomplishments are a confirmation of success while failure to achieve goals is viewed as failure. People are evaluated by what they have or haven’t contributed or accomplished.

Energy is put into meeting goals on time, and striving to achieve as much as possible because this defines the person. There is continual striving, not giving up and unwillingness to accept failure.

If this energy to achieve isn’t successful, unhealthy behavior occurs such as impatience or a disregard or uncaring for anything or anyone who doesn’t contribute to the goal.

The Including Self (Green): A person at this stage defines themselves as equal and caring for others so they listen to, have empathy for and considers others before deciding what to say or do. They are sensitive to those who are disadvantaged or not treated equally or fairly. They consider everyone as important and should be given the opportunity to contribute in their own way. They value collaboration, harmony and cooperation over competition.

Considerable energy goes into including and understanding different people’s perspectives and interests and trying to meet their needs. This can result in comproming to please others or can procrastinating out of fear of hurting or displeasing others. Sometimes, for the sake of equality, lower performance or second best is accepted.

Workplace diversity, equal opportunity and gender bias are issues that live squarely in the green stage.

The Integrating Self (Yellow): A person in this stage identifies with possibilities and potentials. They have a vision of the future and are innovative in finding solutions that integrate previous perspectives into something new. They integrates and synthesizes diverse ideas and create new possibilities. They see things with fresh eyes, even the routine, and look for new possibilities.

In energy used to bring new possibilities is unfulfilled, a person may become impatient because others haven’t had the same insight. This may occurs if he or she hasn’t communicated their vision and insights clearly. If their energy is thwarted in this stage, the person may become removed or depressed because they can’t do what is obvious to them. They may appear as a Don Quixote spending time and effort chasing windmills.

The Integral, Being Self (Turquoise): The person at the Integral self-identity stage aims to be in harmony with life. While they may experience the ups and downs of life, they see themselves as part of the flow of life. They have a spiritual (rather than religious) quality of respect and regard for everyone and everything. At this stage, energy and awareness are in a flow state since the self is free, unbounded and in touch with the ‘Ground of Being’. They see and experience themselves as part of everything. As a zen master said about a person at the integral stage ‘There is just enough ego to walk across the street without getting hit by a truck!’

If too much energy is given to the non-physical, ‘other’ world, the person may neglect everyday, ordinary world events and appear indifferent to people’s concerns or problems and out of touch.

Cook-Greuter, Beck, Torbert, and Cacioppe have applied these same stages to describe leader, team and organization development (Cacioppe, 2009) which provides leaders and coaches a powerful tool to solve current problems and a compass to guide development.

Each stage is a natural evolution from the previous stage and goes through a spiral of moving from an individual to a collective stage and back again. For example, the Controlling stage (collective) occurs after the Asserting stage (individual), since it brings control to the unbridled energy and self-expression of the previous stage. Upon moving to the next stage, the self expands and identifies with a wider and more comprehensive view of life, which Wilber calls ‘Growing Up’. This development through stages is a series of increasingly wider concentric circles of self awareness rather than a hierarchy that dominates lower stages.

Understanding the self-identity stages can help a leader understand behaviours, motivation, values and problems. Leaders can help individuals and teams develop through these stages by asking questions relating to each of them. Examples of questions exploring three of these stages are: Tell me about how secure you feel in your job (beige stage)? I’m curious, tell me which of your important relations at work are going well and which need improvement (purple stage)? Do you get an opportunity to express yourself (red stage)?

Integral Leadership; Developing Mindflow in organizations

Integral leaders help their staff and organizations Wake Up, Show Up and Grow Up. This means helping their staff be more mindful and in flow at work. It also means aligning factors within the four intergral worlds to foster conditions of mindfulness and flow. It also means helping staff and teams develop through the stages of self-identity and to do that leaders must develop through these stages themselves. Integral leaders, therefore, must not only understand, but model mindfulness in flow.

If employees are more aware, satisfied, interconnected and enjoying what they do, then the organization learns, prospers and grows (Wilhelm, 2017). People will be in the moment, connect and learn from each other so continuous learning would part of the organization culture. They would also implement the processes and characteristics of integral, mindful organizations described by Laloux (2014) where activities flow in harmony.

There are considerable bridges that need to be crossed before mindfulness will be embedded in work practices. Reb and Choi (2014,9) state that “business schools are still far away from integrating mindfulness practices, let alone embracing them as a core skill to be taught.” Leaders of the future need to be exposed to these ideas, and a good start would be for universities to incorporate mindfulness, flow and integral leadership in MBA courses and executive leadership programs.

Integral Mindflow programs, which bring together the concepts and skills of mindfulness and flow at the integral point, have been conducted in several companies. While the long-term outcomes are still being evaluated, participants reported considerable benefit in managing stress, improved interpersonal relations, improved work performance and greater experience of flow.

Research is needed to examine the relationship of leadership and mindflow including how development occurs through the stages of self-identity. Greater understanding of the integral point and flow is needed in processes such as strategic planning, financial management, marketing, teamwork, communication and performance management.

The Greek word for work, energia, defines energy, work and flow as the same. Every living thing uses energy in order to obtain more energy to keep living and growing. In ancient Chinese medicine, energy or flow is called Chi. In Yoga, Shakti is primal, universal energy and flows through different centres of the body. In Vedanta philosophy, universal energy or consciousness divides into three forms: tamas, rajas and sattva. And Ki is the Japanese word for the universal energy or life force that flows in all directions, at all times, between all living things.

Integral theory sees the unfolding of this universal energy or spirit as the central process that shapes everything that occurs in the world. Shaping the flow of this energy is the work of Integral Leadership and the Integral four worlds of reality and the eight stages of development provide a map of this unfolding. This map combined with the practical and simple tools of mindflow holds extraordinary potential.

Mathew Fox suggests that there is only one work going on in the universe which he calls the Great Work and I call the Great Flow. It is the creative work and flow of evolution of the universe. When we are practicing mindfulness in flow fulfilling the need of the moment, we are participating in and connected to this Great Flow – or as Eckhart Tolle says: “Life is the dancer and you are the dance.”

About the Author

Ron Cacioppe is the Founder and Chairman of Integral Development, a leadership and organization development company in Western Australia. Ron also is the Visiting Professor at the Antioch University in the Graduate School of Leadership and Change in the Ph.D. program and is currently living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Ron has been a Professor of Leadership at the University of Western Australia and runs mindfulness and leadership development programs in the workplace. He is Deputy Chairman of the not-for-profit Integral Leadership Institute and helped start the Zen Group of Western Australia.

References

Bason, M. R. & Frase, L (2004) Creating optimal work environments: Exploring teacher flow experiences, Mentoring and Tutoring, 12 (2), 241-258.

Blackburn, E. & Epel, E (2017), The Telomere Effect, Living Younger, Healthier and Longer, Grand Central Publisher, New York.

Brown, C. (2002) How to Start a Gurdjieff Group and Other Essays and Letters about the Practical Christianity of G.I. Gurdjieff, Writers Club Press, United States.

Bryce, J. & Hayworth, J. (2002) Wellbeing and flow in sample male and female workers, Leisure Studies, 23, 249-263.

Cacioppe, R. (2009) Integral Potential, An Introduction to Integral Theory and Practice , Bodhi Tree, Perth, Australia

Cacioppe, R (2017), Integral Mindflow, A guide to experiencing mindfulness in flow for fulfilment and excellence in you work, Integral Development, Australia (in publication)

Carli, M., Delle Faye, A., & Massimini, F. (1988) The quality of experience in flow channels: Comparison of Italian and U.S. studies. In Csikszentmihalyi & I. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds) Optimal experience (pp. 288-306) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Carlzon, J (1987) Moments of Truth, New Strategies for Today’s Customer Driven Strategy, Ballinger Publishing, USA.

Ceja, L. & Navarro, J. (2017) Redefining Flow at Work, in Flow at Work, Measurement and Implications, (Eds) Fullagar, C. & Delle Fave, A. pp 81-105

Ceja, L. & Navarro, J. (2011) Dynamic patterns of flow in the workplace: Characterizing within-individual variability using a complexity science approach, Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 32(4), 627-651

Chui, L., & Lee, C. (2012) Exploring the impact of flow experience on job performance, Journal of Global Business Management, 8(2), 150

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990) Flow: the Psychology of Optimal Experience, HarperPerennial, New York

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004) Good Business, Leadership, Flow and the Making of Meaning, Penguin Books, New York.

Dane, E (2011) Paying Attention to Mindfulness and Its Effects on Task Performance in the Workplace, Journal of Management, 37(4) pp. 997-1018.

Davis, D & Hayes, J. (2012) “What are the benefits of mindfulness?”, American Psychological Association Journal, Vol 43, July/August, No. 7, p.64

Davidson R, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, Urbanowski F, Harrington A, Bonus K, Sheridan JF. (2003) Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation, Psychosomatic Medicine, July-August, 65 (4): 564-70.

Engeser, S., Rheinberg, F., Vollmeyer, R., & Bischoff, J. (2005) Motivation, Flow-Erlehen und Lernleistung in univeritaren Lernsetting, Zeitschrift fur Padagogische Psychologies, 19 (3), 159-172.

Fox, M ((1995) The Reinvention of Work, A New Vision of Livelihood for Our Time, HarperSanFrancisco, N.Y.

Fullagar, C., & Kelloway, E. (2009) “Flow” at work: An experience sampling approach, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(3), 595

Flaxman, G. & Flook, L. (2012) “Brief Summary of Mindfulness Research”, UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Centre.

Herrigel, E. (1979) Zen in the Art of Archery, Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd.

Jackson, P. (1995) Sacred Hoops; Spiritual Lessons of a Hardwood Warrior, Hyperion, New York.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990) Full Catastrophe Living; Living the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness, Delacourt, New York.

Kanfer R., Ackerman P. L. (1989). Motivation and cognitive abilities: An integrative/aptitude-treatment interaction approach to skill acquisition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74: 657-690.

Kee, Y., & Wang, C. (2008) Relationships between mindfulness, flow, dispositions and mental skill adoption: A cluster approach, Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 9(4), 393-411.

Killingsworth, M. & Gilbert, D. (2010) “A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind”, Science, 330, November

Kirk U., Downar J., Montague P. R. (2011). Interoception drives increased rational decision-making in meditators playing the ultimatum game. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 5: 49

Laloux, F. (2014) Reinventing Organizations; A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness, Nelson Parker, Belgium

Lee, C. (2004) Adopting the perspective of flow to investigate the effects of participation motivation on voluntary firefighters job-satisfaction, Journal of International Management Studies, 9(2), 113-125

Manocha, R., Black, D., Sarris, J. & Stough, C. (2011). A randomised, controlled trial of

meditation for work stress, anxiety and depressed mood in full-time workers. Evidencebased Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Marelisa, F. (2017) How to Enter the Flow State, https://daringtolivefully.com/how-to-enter-the-flow-state.

Nakamura, J. & Csikzentmihalyi, M. (2009) Flow Theory and Research, Handbook of Positive Psychology, (Eds) Snyder, C., & Lopez, S., Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, pp. 195-206.

Ouspensky Foundation, Exercise File (2015) www.ouspensky.info/exercisefile.htm

Ray, j., Bakes, L., & Plowman, D. (2011) Organizational Mindfulness in Business Schools, Academy of Management and Organizational Learning, 188-203

Reb, J. & Choi. E. (2014) Mindfulness in Organizations, Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University, 1 -31

Reninger, E. (2014) Meditation Now: A Beginner’s Guide, Althea Press, California

Rothbard, N. P. (2001) Enriching or depleting: The dynamics of engagement in work and

family roles. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46, 655-684.

Shachtman, N. (2013) In Silicon Valley, Meditation Is No Fad, It Could Make Your Career, Business, June 18.

Shapiro, S., Schwartz, G. & Bonner, G. (1998) Effects of Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction on Medical and Premedical Students, Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 21, 581-599

Sheldon, K., Prentice, M., & Halusic, M. (2015) The experiential incopatability of mindfulness and flow absorbtion, Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6, 276-283.

Tolle, E. (2000) The Power of Now, A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment, Hodder, Sydney.

Wells, A (1988) Self-Esteem and Optimal Experience, Optimal Experience, Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness, Csikzentmihalyi, M., & Csikzentmihayli, I. (Ed), 327-341.

Whitelaw, G. (2012) The Zen Leader, 10 Ways to Go From Barely Managing to Leading Fearlessly, Career Press, New Jersey.

Wilber, K. (2016) Integral Meditation, Mindfulness as a Path to Grow Up, Wake Up, and Show Up in Your Life, Shambala, Boulder, 2016

Wilhelm, W. (2017) What are Learning Organizations, What Do They Really Do? http//www.clomedin.com/2017/02/22/37471

Williams, M., & Penman, D. (2013) Mindfulness; a Practical Guide to Finding Peace in a Frantic World, Piatkus, Great Britain.

dear sir/ madam I am doing research related to topic mindflow, self-compassion and executive functioning in adolescent from Banaras Hindu University Varanasi India.

please suggest/provide mindflow related scale.

Thank You.