Feature Article: An Integral Approach to Project Management

Brad McManus and Ron Cacioppe

Brad McManus & Ron Cacioppe

Abstract

Projects are an important management approach to improving organisational effectiveness. This paper describes how project management can contribute to achievement of an organisation’s strategy and sustainable success by adopting a more holistic, ‘integral’ approach to a project and the leadership of people during the stages of a project. An integral four quadrant framework for project management is presented that includes a practical and comprehensive approach to change management. The levels of project excellence framework is also described as a way to measure the overall success of a project.

A Project is ‘an individual or collaborative enterprise that is carefully planned to achieve a particular aim…

To cause to move forward or outward’,

Oxford Dictionary

1.0 Project Management versus the Day to Day Management of Organisations

Projects management is an important management tool to implement strategy and achieve an organisation’s strategic goals. Organisations are using projects to adapt to changes in the competitive environment including increasing cost pressures, scarce available resources, global competition, new technologies and a race to get products to customers first (Hyvari, 2006). Projects deliver the most benefit when they are directly linked to corporate strategy (Crawford, 2006; Srivannaboon, 2006).

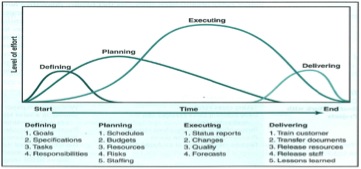

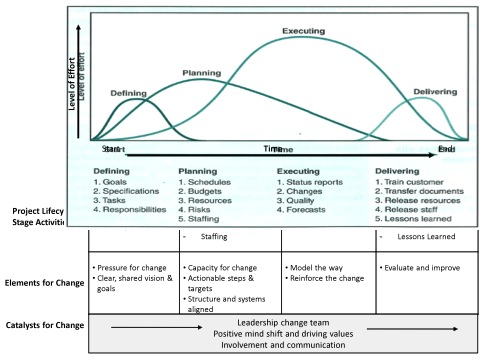

Project management differs from the day to day management of organisations. A project has an established objective, a defined life span, is unique, may involve several departments and professionals, and has specific time, cost and performance outcomes (Gray and Larson, 2006). The fundamental reason for a project is to bring together scarce resources, skills, technology and ideas to achieve future business benefits, or to solve a problem. As projects take place within a specific timeframe it can be said they have a lifecycle. A typical project lifecycle is shown in Figure 1. The figure shows management tasks required at various stages of the lifecycle and the corresponding level of effort required to perform these tasks.

Figure 1: Stages of the Project Life Cycle

(Gray and Larson, 2006)

The project lifecycle is critical to managing the practical implementation of strategy in organisations as it creates urgency, focuses human effort on what needs to be done and when, and provides a timeframe for achieving clearly identified outcomes. Through such an approach, project management can increase productivity for competitive advantage, for example by bringing products or services to market faster than competitors (Kotter, 1990, Hamel and Prahalad, 1994).

In contrast to project management, the day to day management of organisations focuses on routine activities and factors that shape, constrain and prompt managers to act in pursuit of the organisation’s future vision (McKenna, 1999). Day to day management is therefore less focused on time and outcomes, and may be prone to inertia (Meyer, 1999). Organisational goals and objectives are often high level and linked to long term time frames. Practical steps to achieve these objectives may not be clearly identified, therefore reducing the likelihood of successful strategy implementation.

Projects can harness the energy of different thought processes to propel innovation and change in an organisation (Leonard and Straus, 1997). According to Hammer (2000) operational innovation, or the invention and deployment of new ways of doing work, is by nature disruptive and should concentrate on activities that impact on the enterprise’s strategic goals. Stockport (2000, p.46) states, “strategic transformation is about the ability of an organisation to transform itself to ensure long-term survival”. This is to say that innovation and change are necessary to overcome inertia that may exist in functionally oriented organisations. Kenny (2003) cites Dewit and Meyer (1999) to argue that revolutionary projects can help overcome organisational inertia, and must be aligned with the strategic goals of an organisation, rather than a narrowly defined project focus. Nohria et al. (2003) support this argument, and present four primary success factors for projects; strategy, culture, structure and execution.

For projects to enable change and deliver corporate strategy, they should be categorised and prioritised. This may be done by way of project complexity, duration, risk, return on investment or competence of the organisation to deliver (Gray and Larson, 2006). For example, Crawford et al. (2006, p.38) identify the importance of prioritizing the ‘right projects to do’ by way of a portfolio based on return on investment, and having the right competencies ‘to do them right’. It is apparent then that a project must be preceded by a justifiable business case, inclusive of measurable outcomes agreed up front between the project owners and the people responsible for executing the project. Poor project selection can lead to misguided effort, resource wastage and missed opportunities for the organisation.

Cooke-Davies (2002) identifies several factors critical to the success of projects. These include risk management, project duration, benefits delivery and alignment with strategy and business objectives. He highlights the link between project success and corporate success and states, “…it is people who deliver projects, not processes and systems” (p. 189). Turner and Muller (2005) agree and through an extensive literature review point out that the project management literature pays inadequate attention to the impact of a project manager’s leadership style and competence on project success, whereas the general management literature postulates that leadership style and competence have a direct and measurable impact on business performance. This is not to say that leadership alone contributes to project success, moreover that a balanced approach to the management of projects and the leadership of people involved in those projects is required to ensure the effective implementation of strategy. Hyvari (2006) highlights this by identifying planning, organising, networking and informing as significant management and leadership behaviours that contribute to project success.

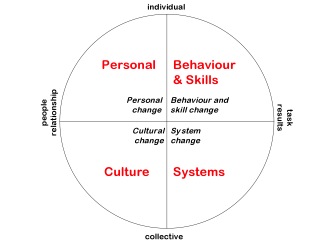

2.0 An Integral Perspective of Project Management

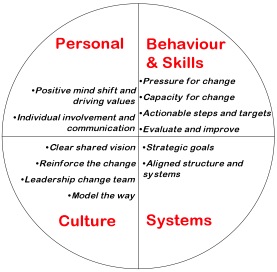

To be fully effective, a holistic and balanced approach to project management is required, one which includes the interconnection of project management and people leadership. Wilber (2000) presents an Integral model which identifies four facets or quadrants of reality. Cacioppe (2009) has adapted Wilber’s model to management and leadership and provides a practical approach that highlights the need to think, decide and act with broad perspective, as well as focussing on the specific tasks at hand. The model implies that a project manager must tend to both relational (leadership) and task (management) related activities to improve the likelihood of project success. This must be done at an individual level and at a collective (e.g. project, team and organisational) level, so that the actions of the project manager align with the culture, vision and strategy of the organisation. A project also involves change to achieve the outcomes it aims for so the model shown below covers the elements of effective management of change.

Figure 2: Integral Four Quadrants of Change

The Integral approach suggests that four facets or quadrants of reality, personal, cultural, behaviour & skills and systems, are important in a project and must be successfully managed. No quadrant is more or less important than another. A manager encountering any problem (e.g. time delays, cost overruns, safety, mistakes, complaints, etc.) that occurs during a project must apply a four quadrant approach if he or she is to adequately define, understand and solve that problem.

The Integral model also provides a lens through which a project manager may view project risks and issues at various stages of the project lifecycle. As demonstrated in Figure 1, the level of effort required during the lifecycle varies. This is important because it is not only the level of effort required that changes over the lifecycle of project, so too does the risk. The chances of a risk event occurring are high in the early stages of a project and can be reduced through clear direction and effective planning. Conversely the cost to fix a risk event is low in the early stages of a project and increases significantly in the execution and delivery stages. Therefore a comprehensive approach to project management that deals with individual, cultural, behavioural/skills and systems will provide a greater degree of success.

The integral lens focuses on more than the narrow task at hand and includes the broader vision, purpose, strategy, culture and leadership required to deliver the project. Importantly, the model can assist in providing a common language for use in relation to a project. Use of commonly understood language is likely to improve communication of the project to people involved. The model also provides a framework for measuring project success, including future benefits, similar to a balanced scorecard approach (Kaplan and Norton, 1998). It does this by focussing on both the internal and external factors which influence project outcomes and stakeholders. Norrie and Walker (2004) present a balanced scorecard approach to operationalising strategy and measuring ‘on-strategy’ project delivery. They emphasize that attaching measures to outcomes strengthens the link between project vision and business strategy.

There are a number of benefits of an integral approach to project management such as:

- Improves communication, cooperation and coordination with stakeholders, alliances and other departments

- Provides a common framework to understand the project purpose and vision, as well as the problems and challenges that arise during the life of the project

- Enables the project team to select appropriate actions such as values, team building, leadership which will help deliver the project on time and within budget

- Creates focus for effective communication throughout the project lifecycle

- Contributes to wider social and natural environment outcomes

- Project members feel satisfied that they have done their best on a project and that they have grown, developed and learned during the project.

So far, the project lifecycle has been identified as important because it creates urgency, focuses resources and identifies the level of effort required at the various stages of a project – design, planning, execution and delivery. The integral four quadrants add perspective to the project lifecycle and highlights management and leadership factors critical to project success. It is the balance between these factors that is critical to effective strategy implementation. The next section identifies elements and catalysts required for successful change. Without these change elements and catalysts, the quadrants discussed thus far remain static and are unlikely to deliver project outcomes consistent with the vision and strategy of an organisation.

3.0 Elements and Catalysts for Change

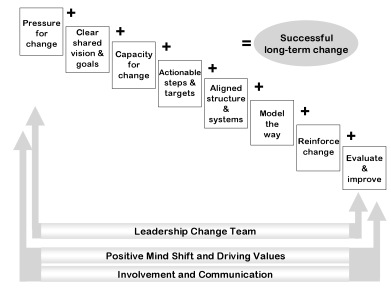

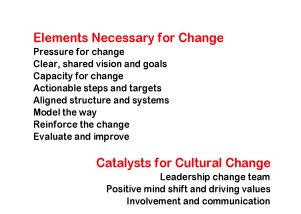

Cacioppe (2008) presents a process to translate leadership vision and management strategy into practical outcomes for an organisational change. The process is relevant to project management and identifies elements necessary for change and catalysts for change. These are shown in Figure 3. The process requires that certain actions must occur prior to and during execution, and if they do not, the desired outcomes are less likely to be achieved.

Eight Elements Necessary for Change

Figure 3: Elements and catalysts necessary for successful change

Figure 3: Elements and catalysts necessary for successful change

3.1 Elements necessary for change

Pressure for change is necessary or employees will not place a high priority on the desired change. Managers and employees have many demands on their time and have many objectives they are working toward. Unless senior managers take definite action to ensure change occurs, employees will respond to other demands. Pressure for change can be from external or internal sources.

External pressure for change can come from sources such as government legislation, political requirements, customer demand, funding cutbacks or increased competition. Major problems such as customer dissatisfaction, poor quality, poor performance and costly mistakes can also result in pressure for change. The CEO of a major hotel decided to initiate an empowerment program after one of their major customers was embarrassed by a hotel staff member who applied the rules of payment too strictly when he tried to order a drink at the bar. The customer told the CEO he would take his company’s business elsewhere if the hotel staff did not become more responsive to customer needs.

Internal pressure can come about, for example, from the CEO setting a new direction or employees indicating dissatisfaction by leaving the organisation. Without this pressure, the change will become a “do it later” or “bottom of the box” low priority change.

A Clear shared vision and goals are needed to help people understand the purpose for the change and to gain commitment to it. A compelling vision is necessary to validate the reason for the project so that it is accepted by the project team.

The vision should have a worthwhile purpose so that people feel their effort is contributing value. Employees need to feel a sense of involvement and to identify with the vision rather than having it imposed on them; they must be able to challenge and test the sincerity and appropriateness of the vision. In some organisations, while managers feel they have a clear vision, it may not have been communicated to employees, who may receive no more than a poster or small card to carry in their pocket as an introduction to the vision. It is important to communicate fully the vision to all employees. If the vision is not understood or shared, employees often make a quick start that fizzles because it is not really understood.

The vision needs to be established early in the life of a project as it provides context for the project plan, and the decisions that follow during the life of the project. It is important at this early stage to identify what outcomes and benefits are sought from the project, and how and when these will be measured. The vision also needs to be shared between project team members to ensure focus and to encourage collaborative effort (Senge, 1990).

Involving managers, staff and key stakeholders in discussions of the vision, values and strategic objectives, helps reach agreement on goals and gains commitment to achieving them. The concept of ‘strategic elephants’ is a very effective way to help determine strategic objectives. Strategic elephants, (from Argenti’s practical approach to strategic planning), are the ‘threats, opportunities, issues or problems that the leaders of organisations or a department have to manage well for it to survive, succeed and/or grow’. Senior executives and staff need to spend time on determining the key strategic elephants facing the organisation. This results in agreed areas to focus on which then become the basis for strategic objectives and actions. Wesfarmers, a very successful Australian organisation, uses the idea of strategic elephants to define and manage many of their major initiatives.

Capacity for change refers to the resources and skills necessary to implement the project adequately. This includes providing appropriate training and allowing adequate time to do what is required. Managers need to plan and budget for the implementation of the project. Often the cost of resources and training is allowed for, but not the time needed to transition to the new way of working. Employees who participate in project teams often complain that managers don’t allocate time for participation in these activities. Employees lose interest because this new initiative is piled on top of their existing work. Lack of adequate resources, time or skill leads to anxiety and frustration.

Actionable steps and targets give employees specific steps to progress the project and tangible outcomes to work toward. Many organisations want to implement projects but do not develop the specific steps and timelines for various stages to occur.

Kotter (1990) highlights the importance of establishing detailed steps and timetables for achieving needed results, and then allocating the resources necessary for making them happen. It is especially important to have actionable first steps which provide the opportunity to start on the change immediately. This element is sometimes called ‘encouraging small wins’ and allows people to feel a positive sense of achievement in the beginning of the project, making them more willing to invest further time and energy. Change projects sometimes fail because management announces a change, such as total quality management, sends people off to training programs, and then allow months to elapse before people are actually required to do things differently. Without actionable first steps, milestone actions and targets along the way, employees make haphazard efforts and false starts.

A project plan outlines responsibility, deadlines and resources required to achieve project outcomes. Nordqvist et al. (2004) examine how deadlines and time resources regulate how work is planned and practiced. They found that team support for the goal and collective ability of the team to some extent moderates the negative effect of time pressure. Like Senge (1990), they add it is important for the project team to share a vision and common goal. Top management support and problem identification have also been directly linked to project success (Belout and Gauvreau, 2003). This support needs to be visible throughout the project, from the defining and planning stages through to the achievement of outcomes. If it is not, the likelihood of a project losing alignment with strategy increases and therefore the desired project outcomes are less likely to be achieved. Crawford et al. (2005) point out the increasing significance of strategic alignment, time management and relationship management to the success of projects.

It is necessary that organisational structure and systems are aligned so that the procedures and processes encourage rather than inhibit progress toward the vision and strategic goals of the project. If systems are aligned, changes can be carried out efficiently, supported by proper procedures and adequate resources. Reward and recognition systems, performance management systems, promotion criteria, customer service and accounting procedures must operate to help achieve and enhance the strategic goals and change management actions. A regular communication system like team briefing that communicates key information and seeks feedback has been introduced by many organisations to ensure staff are informed and involved in the project. If systems are not aligned the project does not get sufficient traction to be effective over a longer time.

Projects and project structures are temporary, therefore the focus and function of projects is separate from, though interdependent with the functional structure and objectives of an organisation. This is unless the firm is project oriented and either is structured around projects, or has a dedicated project management office. A project management office typically sits outside the traditional functional structure of an organisation and can assist in ensuring projects align with corporate strategy and deliver the desired benefits. In large organisations multiple projects are more and more being managed by project management offices (Gray and Larson, 2006).

Butler (1973) highlights the need to balance conflict between traditional functional structures and project structures in organisations. He identifies ‘purposeful conflict’ as a short term managerial device to adapt to important work requirements. For instance, is the employee’s priority to achieve the project objective or the objective of their functional department? Are the two related to one another, and which is more closely aligned with the organisation strategy? In a project environment, resources such as time, people and money are scarce and the potential for political behaviour is significant. Politics, resource competition and conflict in organisations are areas well researched (Butler, 1973; Hocking and Carr, 1996; Kezsbom, 1992). Political behaviour can undermine the success of a project, particularly given that a project involves people from different functional sections of an organisation, with conflicting priorities and differing motives.

Projects are not only becoming more common in organisations they are becoming more complex. Robbins et al. (1994) posit that the more scarce, dynamic and complex the environment, the more organic a structure should be. Although project structures are flexible and temporary, people involved in the project must have clearly delegated responsibility and legitimate authority to effectively carry out the project. If they do not, the likelihood of project success is diminished. Assignment of project responsibility and authority, and the development of project control systems occur at this stage in the Integral Project management process.

Model the way refers to the leaders of the project putting into practice the values and behaviour that reflect the vision. A senior manager’s actions must be consistent with his or her words, or employees will become cynical and distrustful. Managers need to operate with integrity and sincerity so that employees see the actions of their managers as examples of what is expected of them. If customer service is part of the vision of the organisation, managers have to be responsive, positive and willing to make an extra effort themselves for their internal and external customers if they expect employees to act that way also.

It is vital that the CEO is committed to and involved in the change project. If the CEO leaves it to others to carry out the project or does not give his or her personal support and time for the project, employees will give other activities higher priority. Sometimes the CEO may model the way but the members of the senior executive team do not support it or walk the talk. It is vital for the CEO to manage the executive team to be committed to the project and to deal with those senior managers who only superficially support the project.

The next element that is necessary is the reinforcement of the change. This can take a positive form such as reward or recognition from management. Change can be reinforced by memos, newsletters or posters that provide positive messages or examples of successful change. Formal reward schemes or informal praise for actions which support the change, fit into this category. Managers showing interest or spending time with staff involved with the project can also provide extra reinforcement. Steven Jobs, CEO of Apple, spent two years as head of the Macintosh project, demonstrating to everyone in the company that he thought the project was important.

Reward and recognition plays a key role in managing performance and motivating project team members. Career progression should be linked to projects so that people feel their contribution of time and energy leads somewhere. Matta and Ashkenas (2003) argue for breaking complex projects into smaller parts, a series of mini projects, with rapid results to ensure project management achieves an organisation’s strategic goals. Multiple projects can however lead to lack of recovery time, burnout and missed development opportunities for team members (Zika-Viktorsson et al., 2006). This can have a detrimental effect on project performance and on the well being of individuals involved, particularly if inadequate resources have been allocated to the project in the planning stage of the project lifecycle.

Reinforcement can also occur by terminating, transferring or demoting employees who continue to resist the change a project may introduce. If the senior executive does not model the way, employees will revert to the old way fairly rapidly.

The last element for successful change is to thoroughly evaluate and improve the project as it progresses. Change projects that are not evaluated, or are evaluated in ways that are sloppy or superficial, risk being continued or abandoned based on personal feelings, replacement of a manager, lack of money, interest in a new idea that captures the attention of the senior managers. Establishing before and after measures is a way to prove the value of a change project, and avoid people becoming skeptical and the project stagnating.

Many resource companies hold ‘lessons learned’ meetings to review and improve the way the project is operating and improve future projects. The lessons are often stored electronically on central computer systems so they are available to future project teams.

A common evaluation model described by Kirkpatrick involves four areas of outcomes.These include: Reaction which includes a participants’ attitudes toward various aspects of the project, such as communication, job satisfaction and teamwork; Learning measures what knowledge is acquired and what is learned including new skills, new processes such as quality tools or information about the project; Behaviour—this measures the extent to which behaviour has actually changed during the project. This relates to project performance, numbers of injuries, or costs; Results includes the achievement of project goals, profit, improved job satisfaction, fewer injuries and great efficiency.

These four areas relate to the four quadrants of Integral change: Personal=Reaction, Culture=Learning, Behaviour/Skills=Behaviour and Systems=Results. Each of these four quadrants can be used to evaluate to level of excellence of a project. Table 1 provides a general description of five levels within each of the quadrants that can be used to evaluate a project.

| GeneralDescription | People Well-being, Development | Culture, Values,Leadership | Behaviours, Skills, Quality | Systems, Goals & Results |

| LEVEL 5Integral

Project |

High morale, customer and worker satisfaction, good relationships between people on the project, positive community relations, deep personal learning and development | Positive, supportive, learning culture, all values reinforced and lived, ethical, emotionally intelligent and spiritual behaviour | Efficient operations, high quality standard, excellent project and technical skills; Low or no injuries and staff turnover. Environmental action an important part of project | Relevant systems and procedures built into all parts of the project and used consistently.Project achieving time, cost and quality targets, environmental and people targets. |

| LEVEL 4Excellent Project | High morale, customer and worker satisfaction, good relationships between people on the project, positive community relations | Positive, supportive, learning culture, all values reinforced and lived, ethical and emotionally intelligent behaviour | Costs and quality managed well, good project and technical skills injuries and staff turnover at target levels or below, implement positive environmental actions | Systems and procedures carried out and reported consistently.Project achieving time, cost and quality targets. |

| LEVEL 3Good

Project |

Mostly satisfactory customer and worker satisfaction, fair relationships, some community relations | Achievement culture; getting the project done important, safety and values considered | Costs and quality managed well, good project and technical skills, injuries and turnover at target levels or below. Adherence to environmental requirements | Systems and procedures carried out and reported frequently.Project achieving time, cost and quality targets. |

| LEVEL 2Acceptable

Project |

Mixed customer, staff, management or community satisfaction | Neither positive or negative culture, little attention to values | Just acceptable level of costs, quality low, injuries turnover, absenteeism or mistakes | Basic systems, procedures (reporting, production etc.), variable adherence |

| LEVEL 1Unacceptable Project | Customers, staff or management very dissatisfied with project | Negative, confronting culture, values ignored | Costs or quality low, injuries turnover, absenteeism or mistakes too high | Few systems or procedures (reporting, production, safety etc) not adhered to |

Table 1: Levels of Project Excellence

A project team can use this diagram and related diagnostic tools to improve the project at any time. Many organisations conduct project team-building workshops or interpersonal training for projects without determining what level the project is functioning at and what actions would be most useful to move the project to getter levels of satisfaction. Several practical project management tools are available to aid the success of a project. Useful tools include a project scope and brief, stakeholder analysis, risk assessment, project plan, critical event and milestone plans, variations and lessons learned. These tools relate to the systems and behaviour quadrants of the Integral Project Management model. An Integral project management toolkit has been developed by the authors.

4.o Three Catalysts for Cultural Change

A leadership project team is a vital aspect for a successful project. This involves one or more leaders, people with substantial influence in the organisation and important to the project, being personally committed to making the project happens in whatever way they can. A leadership project team can sometimes include the CEO or a very senior person in the organisation who, by their sheer personal influence or position, can help a major project succeed. This can happen where the leader has such presence, vision and communication skills they can influence others to work for them. William Bratton, Police Commissioner of New York City and then Los Angeles, brought significant change to these cities, which reduced crime and boosted the moral of the police service by his extraordinary commitment to making substantial changes in all aspects of the organisation. Senior managers play a critical role in making change effective.

The leadership of a project team could comprise the head of the project, with each manager responsible for a particular aspect of project (resources, cultural change etc). Alternatively, a special project team can be formed which recruits ‘change’ champions, informal and formal leaders, who operate as a planning team, catalyst and reviewer of the project. A senior member of the organisation, ideally the CEO, could also be a member of this group to ensure the project team has influence at the highest level in the organisation. Training in team effectiveness, facilitation, change, and project tools can be very valuable for project managers and the project team.

Change projects frequently fail or stagnate because of the lack of champions for the change or because members of senior executive were not fully committed to the project. This leads to frustration and superficial implementation of the project because people only go through the motions.

Positive mind shift and driving values make up the psychological and emotional atmosphere that supports the project. Many projects encounter resistance because staff have a negative mindset and attitude toward the changes it brings. Shifting people’s attitudes and negativity is essential so that the culture of the organisation supports rather than inhibits the change.

Thamhain and Gemmill (1974) argue that the success of a project manager is directly linked to their ability to elicit support, agreement and involvement amongst members of the project team. Drucker (1998, p.10) states that, “… full time employees have to be managed as if they were volunteers… They need, above all challenge. They need to know the organisation’s mission and to believe in it”. The same applies to members of a project team. Prabhakar (2005) highlights the importance of team leadership and the team related factors to project success. He adds that project managers who demonstrate transformational leadership or more specifically, inspiration combined with a care for people enjoy greater project success.

Shifting people to a positive mindset means helping them become aware of their mental self-talk and teaching them to drop negative thoughts and attitudes. Negative self-talk is replaced with positive attitude or no self-talk. People can learn to approach situations with a clear mind and positive outlook. Meditation programs have been introduced in many organisations to help this. If staff can approach a project and its challenges with a positive rather than a negative attitude there will be a much greater chance of success.

Many organisations have a set of values that staff are asked to live by when they interact with suppliers, other staff and customers. Often these values are espoused but not lived. When a project is carried out, these driving values must genuinely underpin the type of change being implemented in the project. For example, if the organisation is introducing new services and products, the driving value might be innovation. Large energy companies and banks have conducted workshops in which staff are taught to look at their values and how they are to be built into the project.

Henrie and Sousa-Poza (2005) point out that projects are becoming more complex in part due to interaction between the social and technical aspects. Brookes et al. (2006) highlight the need for building both knowledge and good relations in projects. They recommend sharing of practical knowledge of the project which leads to organisational learning. According to Garvin (1993, p.80), “a learning organisation is an organisation skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge and insights”. Learning organisation theory emphasizes personal mastery and intrinsic motivation. Senge (1990, p.206) states “…the tools and techniques cannot be separated from the vision and the values of the learning organisation”. Senge’s theory makes the connection between management and leadership factors contributing to project success.

Involvement and Communication is the third catalyst for change. People need to be continually informed about the project through various methods (e.g. one-to-one discussions, project meetings, team briefings, newsletters, emails etc.). They also need to have a say in what will work and what needs to be done differently regarding the project. Their valid suggestions need to be taken on or else employees will lose interest and become disillusioned.

Effective communication underpins effective project management, so shouldn’t be left to chance. Clear communication of a project purpose and goals can focus effort, build teamwork across functions and establish mutual accountability between project team members. Katzenbach and Smith (1993, p.116) identified that teams establish a social contract among team members based on trust and, “…when a team shares a common purpose, goals, and approach, mutual accountability grows as a natural component… Goals help a team keep track of progress, while a broader purpose supplies meaning and emotional energy”.

A clearly communicated and well led project can stimulate innovation and learning, which in turn can create competitive advantage for an organisation. Gamble and Procter (2001) emphasise the importance of fostering communities of practice to leverage knowledge, and to enable these communities both through face to face contact, and through collaborative electronic media such as web pages, video conferences and chat rooms. Majchrzak et al. (2004) concur and point to collaborative technology, such as the intranet, to help people in project teams work faster, smarter, more creatively and flexibly, than dispersed individuals or an enterprise as a whole.

It is important for the project purpose to be clearly communicated to those directly involved, and more broadly to other people affected by the project. Projects inevitably have several stakeholders, with relationships that are interdependent and with different motives. Therefore a project manager should be able to deal with the complexity of managing multiple tasks and relationships, and in doing so effectively communicate with all project stakeholders.

5.0 Project Life Cycle and Successful Change

The elements and catalysts for successful change can be usefully integrated into the project lifecycle shown earlier. Figure 4 below shows the four major phases of a project and the elements of change that are needed during these phases to help the project succeed. This diagram provides useful guidance for a project manager who wants to ensure each phase is carried out successfully.

Figure 4: Elements and Catalysts of Change within the Project Lifecycle Stages

Including appropriate actions at each stage (e.g. a clear shared vision at the beginning) a project team not only complete tasks and technical challenges but will also have the subtle aspects needed for people to feel they own and are committed to the whole project from beginning to end.

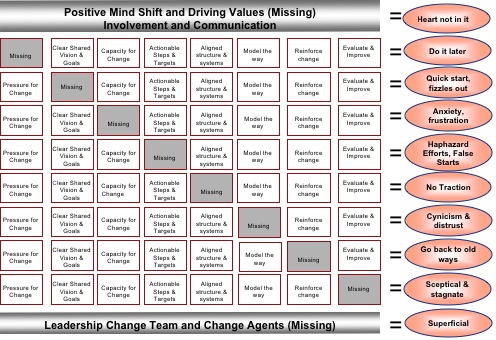

6.0 Using the Integral Project Change Model to Bring About Successful Projects

The Integral project model has considerable relevance and value when it is used to plan and implement new projects or examine existing ones. Using these dimensions to analyse change gives a thorough analysis of the real outcomes of the change project, or program of projects. This information can be used to determine whether the project should continue or be improved in some way. Figure 5 below shows the symptoms that will occur if any of the elements and catalysts needed for successful projects is missing. For example, if pressure for change is missing then the change will be a low priority and it will be postponed. If a clear vision is missing, the project will undergo a quick start but will fizzle out.

Figure 5: Symptoms when factors are missing

This figure can be used to help diagnose the progress of the project and areas for improvement. Employees undergoing a change project have been shown this figure and asked to identify which symptoms they are experiencing. They have been able to quickly identify the problems they have experienced. Usually two or three boxes are highlighted as the ones of most concern. Staff are then asked to discuss ways a factor can be improved. They often come up with clear, specific ways the project can be improved. For example, one group, who felt that there was no clear shared vision, asked the project manager to hold meetings in each location to clarify the project vision and objectives. They wanted to ask him questions, make suggestions and for him to listen to their recommendations on what could be done to help the project succeed. This was a straight forward and worthwhile suggestion that went ahead, and the ideas that came out of the meetings worked well in helping the project to be more successful. A number of organisations including a national postal service, a large Australian conglomerate, an energy company and a local government have used this model to evaluate change. One organisation now requires all their managers to submit new project requests in a format that shows all the elements in Figure 4 are covered.

A survey of these factors can indicate which areas can be improved. When given to all staff involved in the project, the results can provide an objective measure of which are going well and which factors need to be improved. This can also provide a baseline measure to monitor progress of the change project.

A ‘project change team’ can be formed to make recommendations to management on how each of these factors can be improved. Both staff and management have found this model easy to understand and use. In addition, it fits with practical experience and can provide an effective way to discuss, evaluate and improve the change project. In today’s environment, managers cannot continue to subject staff to change initiatives without ensuring they are successfully managed.

7.0 A Comprehensive and Practical Model for Change Projects

Figure 6 shows where each of the elements and catalysts for change fit into the Integral four quadrants. All of these quadrants must be dealt with if a change is to succeed and last.

Figure 6: Four Quadrants of Integral Change

While many change projects deal with two or three quadrants, few deal with all four quadrants. One major energy company introduced a major change project that covered the personal and cultural quadrants but ignored the skills, performance appraisal and its strategic planning and business systems. Staff morale went up but the company lost its competitive advantage and the share price fell. As a result, a new CEO was brought in and the change program was dropped.

The elements and catalysts essential for successful change covered are the four areas of reality: personal, cultural, behavioural and system change. They provide an effective guide to ensure the change project works well.

The Integral framework for projects is a comprehensive approach and can be used to guide large-scale change or to analyse existing change projects. It is also a very practical and easy approach for leaders, managers, supervisors, human resource professionals and consultants to use. At a time when organisations are trying to implement so much change, the Integral perspective provides both the compass and the map to ensure people and teams get to where the change is supposed to take them.

8.0 Conclusion

Projects provide managers with a practical means of adapting actions, culture, behaviour, skills, systems and structure to bring opportunities into reality. Enhancing a project’s effectiveness and outcomes can create a competitive advantage for an organisation. A project manager must adopt both management and leadership skills to ensure project success. The Integral Project Management and Leadership approach provides a framework to do this by integrating four key elements:

1) The project lifecycle which creates urgency, focuses resources and identifies the level of effort required at the defining, planning, executing and delivering stages of a project

2) An integral perspective which includes four quadrants or perspectives of reality including personal, cultural, behaviour and skills and systems all of equal importance to successful leadership and management of a project

3) The five levels of Integral project management provide a clear way of evaluating the project in terms how well the integral four quadrants are being implemented.

4) Eight elements and three catalysts required for successful implementation of a project. If one or more elements or catalysts are missing then the likelihood of achieving successful project is reduced.

An Integral framework for project management can improve the likelihood of a project achieving the strategic goals of an organisation. It also provides a balanced scorecard for measuring project outcomes and benefits. Using a comprehensive integral framework will result in projects that meet project targets, develop people, systems, behaviours and a culture that bring long term sustainable success to the organisation.

References

Belout, A., & Gauvreau, C. (2004), Factors influencing project success: the impact of human resource management. International Journal of Project Management, 22, pp. 1-11

Butler, A.G. (Jnr.), (1973), Project Management: A study in organizational conflict, The Academy of Management Journal, Vol.16, No.1, Mar, pp.84-101

Cacioppe, R. (2000), Creating spirit at work: re-visioning organization development and leadership – Part II, Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 21/2, pp. 110-119

Cacioppe, R. (2009) Integral Potential; An introduction to Integral Theory and Practice, Integral Development, Perth, Australia

Christenson, D. & Walker, D.H.T. (2004), Understanding the role of “Vision” in project success, Project Management Journal, Sep; 35, 3; ABI/Inform Global, pp.39- 56

Cooke-Davies, T. (2002), The “real” success factors on projects. International Journal of Project Management, 20, pp 185-190

Crawford, L., Pollack, J., & England, D. (2005), Uncovering trends in project management: Journal emphases over the last 10 years, International Journal of Project Management, 24 pp. 175-184

Crawford, L., Hobbs, B. & Turner, J.R. (2006), Aligning capability with strategy: Categorizing projects to do the right projects and to do them right, Project Management Journal; Jun. 37, 2; ABI/INFORM Global, pp.38-50

De Wit, B., and Meyer, R. (1999), Strategy synthesis-resolving strategy paradoxes to create competitive advantage. London, International Thompson Business Press; In Kenny, J. (2003). Effective project management for strategic innovation and change in an organizational context; Project Management Journal, Mar; 34.1; ABI/Inform Global, pp. 43-53

Drucker, P. (1998), “Management’s new paradigm”, Forbes, New York, Oct.5, Vol.162, Issue 7, pp. 152-177

Gamble, P.R. & Blackwell, J. (2001), Knowledge Management: A State of the Art Guide, Kogan Page, London, pp.73-98

Garvin, D. (1993), “Building a Learning Organisation”, Harvard Business Review, Jul-Aug; pp. 78-91

Goleman, D. (1995), Emotional Intelligence; Why it Can Matter More Than IQ, Bloomsbury, London, pp.46-55

Gray, C.F., & Larson, E. (2006), Project Management: The Managerial Process, McGraw Hill, Australia, p.6, pp 312-333,

Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C.K. (1994), Competing for the Future, Harvard Business School, Boston, MA

Hammer, M. (2004), Deep change: How operational innovation can transform your company, Harvard Business Review, April, pp.85-93

Henrie, M. & Sousa-Poza, A. (2005), Project management: A cultural literary review, Project Management Journal; Jun.; 36, 2; ABI/INFORM Global, pp.5-14

Hocking, J. & Carr, A. (1996), Culture: the search for a better organisational metaphor”, Oswick, C. and Grant, D., eds, Organisational Development, Metaphorical Explorations, Pitman, London, pp. 73-89

Hyvari, I. (2006), Project management effectiveness in project oriented business organisations, International Journal of Project Management, 24 pp. 216-225

Hyvari, I. (2006), Success of projects in different organizational conditions, Project Management Journal; Sep; 37, 4; ABI/INFORM Global, pp.31-41

Kaplan, R.S., & Norton, D.P. (1998b), Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system. Harvard Business Review on Measuring Performance, pp. 183-211

Katzenbach, J.R. & Smith, D.K. (1993), The discipline of teams, Harvard Business Review, March-April, pp.111-120

Kenny, J. (2003), Effective project management for strategic innovation and change in an organizational context; Project Management Journal, Mar; 34.1; ABI/Inform Global, pp. 43-53

Kezsbom, D. S. (1992), Re-opening Pandora’s Box: Sources of project conflict in the ‘90s, Industrial Engineering; May; 24, 5; ABI/INFFORM Global, pp.54-59

Kotter, J. (1990), A Force for Change; How Leadership Differs From Management, The Free Press, New York, pp. 6-12

Leonard, D. & Straus, S. (1997), Putting your whole company’s brain to work, Harvard Business Review, 75(4), pp.111-121

Majchrzak, A., Malhotra, A., Stamps, J., & Lipnack, J. (2004) Can absence make a team grow stronger? Harvard Business Review, May, pp.131-137

Matta, F. N., & Ashkenas, N. R. (2003), Why good projects fail anyway, Harvard Business Review, September, pp.109-114

McKenna, R. (1999), New Management, Irwin McGraw-Hill Australia Book Company Pty Ltd, pp.5-11

Nohria, N., Joyce, W., & Roberson, B. (2003), What really works, Harvard Business Review, July, pp. 43-52

Nordqvist, S., Hovmark, S., & Zika-Viktorsson, A. (2004), Perceived time pressure and social processes in project teams. International Journal of Project Management, 22, pp. 463-468

Norrie, J. & Walker, D.H.T. (2004), A balanced scorecard approach to project management, Project Management Journal; Dec.; 35, 4; ABI/Inform Global, pp.47-56

Office of Government and Commerce UK, (2007), Available online at www.ogc.gov.uk/methods_prince_2.asp

Prabhakar, G.P. (2005), An empirical study reflecting the importance of transformational leadership on project success across twenty-eight nations, Project Management Journal; Dec; 36, 4; ABI/INFORM Global, pp. 53-60

Robbins, S.P., Waters-Marsh, T. Cacioppe. R. & Millett, B. (1994), Organisational Behaviour: Concepts, Controversies and Applications, Prentice Hall Australia Pty Ltd, pp. 642-679

Rozenes, S., Vitner, G. & Spraggett, S. (2006), Project Control: Literature Review, Project Management Journal, Sep; 37, 4; ABI/Inform Global, pp.5-14

Senge, P. (1990), The Fifth Discipline; The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Random House, Australia, pp. 139-173

Srivannaboon, S. (2006), Linking project management with business strategy, Project Management Journal, Dec; 37, 5; ABI/Inform Global, pp.88-96

Stockport, G. (2000), Developing skills in strategic transformation, European Journal of Innovation Management, Volume 3, No.1, pp.42-52

Tsoukas, H. & Chia, R. (2002), On organizational becoming: rethinking organisational change. Organization Science, 13 (5), pp 567-582

Thamhain, H.J. & Gemmill, G.R. (1974), Influence styles of project managers: Some project performance correlates, The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 17, No.2 (Jun.), pp. 216-224

Turner, J.R. & Muller, R. (2005), The project manager’s leadership style as a success factor on projects: A literature review, Project Management Journal; Jun: 36, 2; ABI/INFORM Global, pp.49-61

Wideman, M. (2002), Comparing PRINCE2 with PMBoK, AEW Services, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Wilber, K. (2000), ‘A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality’, Shambhala Publications Inc., Boston

Zika-Viktorsson, A., Sundstrom, P., & Engwall, M. (2006), Project overload: An exploratory study of work and management in multi project settings, International Journal of Project Management, 24, pp. 385-394

Oxford dictionary definition available online at http://oxforddictionaries.com/view/entry/m_en_gb0665380#m_en_gb0665380

About the Authors

Ron Cacioppe, PhD, is Chairperson of Integral Leadership Institute in Perth, Western Australia. He holds a BSc., an MBA and a PhD. Ron is Managing Director of Integral Development and has been a leadership and organisational development consultant for over thirty years working with business, government and not-for-profit organisations in Australia, Asia and the United States. He has taught in the Graduate School of Management at Macquarie University, Curtin University and the University of Western Australia and currently teaches at the MBA level in the areas of Leadership Effectiveness, Leading and Facilitating Teams, Managing Strategic Change and Philosophy and Leadership. He is Adjunct Professor Adjunct Professor at Curtin University’s Australian Sustainable Development Institute.

Brad McManus is Vice Chairperson at Integral Leadership Institute in Perth, Western Australia. He holds an MBA and a Master of International Business. Brad is a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Company Directors, the Australian Human Resources Institute and the Chartered Management Institute in the UK. He is also Director of Organisational Capability and a Senior Consultant at Integral Development, and Founder of The Sustainability Centre in Thailand. Brad has over 17 years senior executive experience leading organisations and projects in the corporate and not for profit sectors.

[…] Integral to Work: An Interview with Laura Roberts, CEO, Pantheon Chemical—Russ VolckmannArticlesAn Integral Approach to Project Management—Brad McManus and Ron CacioppeLeadership for Sustainable Change—Vernice SolimarLeading in […]

Hi Ron/Brad,

That’s an excellent article that qualifies as a complete introduction to project management.

I would like to republish it on PM Hut ( http://www.pmhut.com ), a website that is visited and loved by many project managers every day. Please either email me or contact me through the contact us form on the PM Hut website in case you’re OK with this.