12/21 – Developing an Inclusive Perspective for a Diverse College: Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement

Cheryl Whitelaw

Cheryl Whitelaw

Cherly Whitelaw

Abstract: This article describes a project at the NorQuest College Center for Intercultural Education to develop an inclusion model for a post-secondary, two-year college. Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement is a model for action based on the integration of Integral theory, particularly the all quadrants component of the AQAL model by Ken Wilber and the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity by Dr. Milton Bennett. The author views inclusion as a perspectival phenomenon, socially constructed; a culture of inclusion is, in part, founded on perspective seeking behaviors. Within the model, the focus for translative and transformative change is guided by the Intercultural Competence Stretch Goals document, a map created by the author and her project collaborators to identify selected attitudes, knowledge and skills to support more inclusive communication behaviors. Within the context of a college with identifiable diversity in terms of country of origin, languages spoken, race, ethnocultural origin including First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples and the level of ability requiring supports (for physical and/or learning challenges), this article describes an applied research project to generate the Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model and the organizational change initiatives that flowed out of the model. These organizational change initiatives are continuing through an ongoing inclusion focus at NorQuest College in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Although written from a single author perspective, I want to acknowledge the project team members and the community of participants that engaged in this project from project proposal to ongoing inclusion initiatives. [1]

An abiding question in a two-year community college with a 40 year history of serving a diverse student population is one of inclusion. As a learner-centered College with visible services and facilities to accommodate and adapt to the diverse needs of the learners who attend, this is an institutional performance benchmark with heart. What is inclusion? What does it look like? How do we understand and learn from the perspectives of inclusion and exclusion? How do we know how we are doing? Do our systems and environments support or deter inclusion? For people who are motivated to put Integrally informed theory into action, this article will review the creation of a theory for action model currently in use to guide NorQuest College to embody its organizational value of inclusion. The theory for action model has tapped a deep-seated desire to engage and empower the adult learners who come to the college and is catalyzing that desire into action at NorQuest College. The model has also illuminated where work is needed to achieve an inclusive college.

What is Inclusion? Changing the Conversation

What is inclusion? Operationally at NorQuest, inclusion has been understood and acted upon as a focus to reduce barriers for adult learners to participate in education with the aspiration of supporting student success. Student success has been striven for in both institutional (program completion, learner retention) and individual terms (student satisfaction with learning experience, completion of learner goals). With the establishment of the Centre for Intercultural Education in 2009, the perspective of inclusion has taken a different shape. We began to explore inclusion as a “socially constructed reality,” (Ford, 1999, p. 480). Ford describes first-order realities, the “physically demonstrable and public discernible characteristics, qualities, or attributes of a thing, event, or situation,” and second order realities, as “created whenever we attribute, attach, or give meaning, significance, or value to a first-order reality” (Ford, 1999, pp. 481-482). The consequences of this meaning-making activity can create “concrete results of a personal and societal nature…First and second-order realities are rarely constructed solely by direct personal experience, but are inherited in the conversational backgrounds (e.g. cultures, traditions, and institutions) in which we are socialized…Socialization gives us instructions on how to see the world, and we operate as if the world really is that way” (Ford, 1999, p. 482-483). We considered how inclusion could be understood as “networks of conversations constituting a variety of first and second-order realities” (Ford, 1999, p. 485). Seeking to build on demonstrable and visible components of inclusion (i.e.. programs and services targeting learners with specific needs), we focused on conversations as a way to nurture an existing culture of inclusion, not solely from a top-down or special interest group agenda but as a co-created one, a conversation in which everyone is welcome to contribute their voice and perspectives.

Inclusion through Intercultural Competence

We joined this conceptualization of inclusion in the NorQuest Center for Intercultural Education’s mission to cultivate intercultural competence. At the Centre, we seek to promote intercultural competence in Canada through applied research, training and education using a developmental model of intercultural competence. The Centre’s focus for intercultural competence is within the interaction space between people, on growing the mind, heart and skill sets to engage others through the lens of this competence. The Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity or DMIS (Bennett, 1993), describes intercultural competence as a developmental continuum of increasing capacity to perceive, accept and adapt to similarities and differences in the cultural worldviews we encounter. In the model, cross-cultural experiences are constructed ones; we typically create meaning using sets of categories based on our experiences within our own cultural worldview to organize our perception of observable facts. Our categories influence our perspective, how we create our second order reality. Robert Kegan notes, “the failure to take responsibility for the invented nature of our meaning-constructions when these constructions are regulated by culture is in fact the essence of ethnocentrism” (Kegan, 1994, p. 206).

A Developmental Approach to Intercultural Competence

In the DMIS theory, the developmental continuum describes stages of cognitive complexity and the behaviors arising from our cognitive capacity, ranging from a mono-cultural or ethnocentric mindset, (the capacity to explain and interact with similarities and differences from our own, familiar cultural worldview) to an ethno-relative or intercultural mindset, (the capacity to explain and interact with similarities and differences within more than one cultural worldview).

Figure 1: Developmental Model for Intercultural Sensitivity – Intercultural Development Continuum

In this model, developing intercultural competence is creating an increasingly complex capacity to perceive similarities and differences, to accept those as part of a dynamic and complex worldview. From this perspective, choices informed by a plurality of worldviews can guide how we respond to intercultural encounters. The Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) is a validated psychometric tool designed to measure the orientations toward cultural differences described in the DMIS. In IDI-guided interventions to enhance intercultural competence, the IDI profiles allow intercultural facilitators to target the DMIS stage development needs and to facilitate both translative and potentially transformative learning. Key to intercultural competence is the capacity to take perspectives on, other than our own. Developing this capacity includes both translative development, the knowledge, skills and attitudes that comprise intercultural competence and transformative development, an increasingly complex capacity to perceive and act through the lens of this competence to engage with diverse people, contexts and interactional containers. The view of similarities and differences from an ethnorelative worldview is transformationally different from an ethnocentric worldview. An ethnorelative view can be said to transcend and include an ethnocentric one.

Perspective Taking – What is Includable?

Interculturally competent people are adept at and have the capacity to engage in perspective-taking, to look at their own assumptions and categories of interpretation as well as those of other people. The capacity to look at one’s own perspective creates the spaciousness, the possibility to choose how to act on the information generated from these sense-making processes. The heart of this developmental approach is the observation that a sufficient capacity to take perspectives – to understand and engage with what is unfamiliar to us is core to positively engage people with differing worldviews. Kegan notes, “A friendly naiveté becomes ugly because if someone is includable, it is because his difference can be translated to what we take to be real, and if his difference cannot be so translated, he is not includable.” (Kegan, 1994, p. 208). This capacity to look at our own meaning-making categories and behaviors arising from our interpretative frameworks was a core goal for the Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model and the inclusion-promoting activities arising out of the model.

This developmental approach to intercultural competence is one of many theories to shine a light on the complex phenomenon of the capacity to positively and productively engage with diversity. Each theory shines a light on aspects of this phenomenon within different contexts. The Developmental Model of Intercultural Maturity explores this capacity as a multidimensional framework including cognitive complexity, intrapersonal capacity (how people think and come to understand diversity issues as relate to identity) and an interpersonal dimension (the ability to interact effectively and interdependently with different others (King & Baxter, 2005). The Intercultural Competence Process Model explores the degree of intercultural competence depending on acquired degrees of attitudes, knowledge/comprehension and skills with an emphasis on movement from individual level attitudes to interaction level outcomes (Deardorff, 2006). The Multicultural Competence model identified core competences for student affairs practitioners and faculty to embrace multicultural issues including race, class, religion, gender, sexual orientation, age and abilities (Pope, Reynolds & Mueller, 2004). At an organizational unit of analysis, the Cultural Continuum model examines organizational capacity for cultural competence within the context of care systems (Cross, Bazron, Dennis & Isaacs, 1989). A recent consensus on key characteristics of intercultural competence was identified by a panel of American and international scholars documented in the Intercultural Knowledge and Competence Value Rubric (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2006). These characteristics of intercultural competence include cultural awareness, knowledge of cultural worldviews, empathy, verbal and non-verbal communication, curiosity and openness. We chose this rubric as a reasonable representation of core characteristics for intercultural competence to use in our Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model for action.

Figure 2. Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model for action

Inclusion in Action: Student Services

To begin a different conversation for inclusion, in our initial project, we choose the student service interaction as a focus for intervention, study and the container for the conversation of inclusion (and exclusion). This choice for an inclusion study and for an inclusion intervention built on the existing institutional culture of student services with a focus on removing initial barriers for students. Our initial intervention was a 15 hour inclusion training program customized for service staff at NorQuest College[2]. Part of the approach to the inclusion training was acknowledging the need for repeated practice to see from another’s perspective and the surfacing of the motivation to “exert the mental effort necessary to adopt another’s perspective” (Epley & Caruso, 2009, p. 300).

In the context of inclusion at a college, a key precept for the Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model is that inclusion is a perspectival phenomenon, socially constructed by the people engaged in interactions within the institution. Fuhs’ definition of perspective-taking provides both clarity and utility. He describes perspective taking as, “the developing capacity of a subject to become aware of and consequently take or seek the perspective of a real or hypothesized individual or group with the intent to use the information about the object dimension enacted for some instrumental purpose” (Fuhs, 2013, p. 8).

In the context of a student service interaction, inclusion and perspective-taking action is bounded by the service goal, the context and potential constraints of the service context (e.g. rules related to student funding, time constraints for each front-line service interaction, etc.). We wanted to ensure that perspective-taking within an inclusive student service interaction was anchored to the goals of the service provided or requested, the context of the service as well as the cultural characteristics of the staff and students participating in a service interaction. Our operating hypothesis was that inclusion in this service interaction becomes more possible when the shared capacity of college community members is situated within or developing towards an ethnorelative or intercultural mindset.

Staff Developmental Orientation to Intercultural Competence

In our organizational context, we have conducted IDI guided consultations and training for different staff groups in the College. As part of this work, we obtained ethics approval to compile an aggregate profile of IDI scores in order to establish a benchmark for College staff and target more specifically our training interventions. Over the last 2 years, 5 different staff groups voluntarily participated in our IDI data collection. A compilation of these results shows that College staff are primarily clustered within the ethnocentric stage of minimization.

Figure 3. Compiled Intercultural Developmental Inventory Profile Scores – Minimization Cluster

Within the DMIS, this stage has been described as ethnocentric (Hammer, Bennett & Wiseman, 2003). From a minimization worldview, people from other cultures are pretty much like you, under the surface. Within a minimization perspective, you are quite aware that other cultures exist all around you, and you may know something about cultural differences in customs, celebrations, or other objective artifacts of cultural traditions. You tend not to denigrate other cultures and you seek to avoid stereotypes by treating every person as an individual or by treating other people as you would like to be treated. One of the strengths of this perspective is recognizing the essential humanity of every person and trying to behave in tolerant ways towards others. One of the challenges of this perspective is the focus on commonalities that can mask deeper recognition of cultural differences. You may miss or minimize the differences that make a difference. So in pursuing a model of inclusion, acknowledging the potential to entrench a mainstream Canadian organizational and cultural view under the guise of helping our diverse students to ‘fit in,’ we decided to emphasize the importance of creating opportunities for engagement with diverse perspectives. From this minimization worldview, opportunities for growth come through practice in understanding one’s own perspective and the perspectives of others.

Barriers to Perspective Taking

Following one of the implications of a developmental model of intercultural sensitivity to enact a more inclusive organizational culture, what barriers exist at a predominantly ethnocentric worldview to take the perspective of another? If the ability to perceive difference is primarily framed through the lens of what is familiar, the information available to a person, with positive inclusion intent and goals, will be necessarily limited to the degree of difference that can be perceived and included from their stage of development. Fuhs discusses the factors that affect accuracy in perspective taking, the sources of information about a person (e.g. “dress, facial expression, movement, voice quality, and verbal statements,…past experience with the [person],…,subject’s perceived self-similarity to target,….perceived in-group similarity and out group stereotypes;…and other people’s perspectives regarding the target” as well as information about the context that “influences expectancies” (Fuhs, p. 17, 2013). He notes that limits to perspectival accuracy can also be shaped by “task demands, attentional constraints, and egocentrism may prevent accessible information from being selected as relevant” (Fuhs, 2013, p. 17). “Because one’s own perspective tends to come to mind more rapidly, readily, and reliably than information about others’ perspectives, one’s own point of view may tend to serve as the default perspective for interpreting the world (Krueger, 1998 cited in Epley & Caruso, 2009, p. 300).

Perspective taking requires work; to overcome our own egocentric experiences, to seek information that accurately relates to another’s perspective and not simply a projection of our own requires significantly more effort than mining our self-centric experiences to reach judgements about another’s perspective (Epley and Caruso, 2009). Epley, Caruso and Bazerman found repeated evidence that people behaved more selfishly in competitive scenarios when asked to consider the perspective of others than people who acted considering only their self-interest. While considering another’s perspective did “diminish ego-centric assessments of fairness, this reduction led to a “reliable tendency for reactive egoism in competitive groups” (Epley, Caruso and Bazerman, 2006, p. 886). This kind of “reactive egoism” or self-serving behaviour was not demonstrated when the social interaction was framed as a cooperative one. The authors distinguish between a “cognitive perspective taking” and other ways of taking perspective including empathizing, simulation and visualizing (Epley, Caruso & Bazerman, 2006, p. 873). Their inference is that “considering others’ concerns and interests activates beliefs about others’ behaviour, which, in turn, lead people to behave more selfishly themselves.” (p. 877). This reactive egoism is more likely to occur when taking the perspective of a member of an out-group vs. a friend or other in-group member (p. 887).

Perspective Taking to Perspective Seeking

In nurturing a culture of inclusion and building shared competencies to engage positively across cultural and other differences, we identified the need to situate interventions beyond a cognitive perspective taking exercise to a more embodied experience. Within the inclusion training and in other organizational activities guided by the Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model, we focused on creating intercultural spaces to give both permission and opportunity for “perspective-seeking” activities (Fuhs, 2013, p. 20). To focus more accurately on the knowledge, skills and attitudes for the practice of a more embodied perspective-seeking, we created a framework, the Intercultural Competence Stretch Goals framework, to better identify the developing edge of core intercultural competence for each stage described in the DMIS. The Stretch Goals document is based on the 6 core characteristics for intercultural competence in the Intercultural Knowledge and Competence Value Rubric (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2006), describing the skill, knowledge and attitude at each stage in the intercultural continuum as described the DMIS. For example, in describing the attitude of openness, we emphasized the demonstration of openness by how we work with our judgments, attending to the link between judgments and behavior within an interaction.

Building on the stage description of minimization from the DMIS, we proposed that a person oriented from this worldview is open to interactions with culturally different others, yet may have difficult suspending their own judgment. This person is beginning to see their own perspective as a perspective and tends to view much of their perspective as superior or correct. Within this orientation, a person may be willing to review and change some of his or her judgments and may be willing to examine cultural patterns as the basis for their own behaviour. The stretch goals for a person from this orientation is beginning to suspend their own judgments, refrain from stereotypical responses and ask from a stance of open curiosity questions to establish a deeper level of connection with another person.

The stretch goals also include a growing recognition that other cultures have different views and ways of communicating. As a stretch goal, a person in this orientation may begin to attempt to shift their own communication style in certain contexts with a focus on better understanding their own perspective and increasing their ability to notice other communication styles.

One of the key insights in developing the stretch goals was how, generally, in our training practice, we had been engaging our learners from our own developmental perspective. By making visible the stretch goals at each stage, we realized that we had to honor and meet our learners just in front of their stage, to align with their perspective and engage them just a little bit more, to elicit the beginning of a transformative learning experience. For this kind of developmental movement, changing behavior can be one way to enable transformative development with an underlying process of learning, reflection to make sense of experiments in behavioral change (Deardorff, 2006). I suggest that adding communication styles without a sense making, frame-shifting reflection process is more likely to result in a translative development, increasing the set of communication competencies without necessarily changing perspective-taking capacity overall.

Changing the Conversation to Co-Create Inclusion

We wanted to change the conversation so we could, together, construct the reality of inclusion at NorQuest College. We knew from IDI profile scores that a majority of our initial participants were situated in an orientation to differences and similarities that tends to prefer or privilege their own familiar perspective with a smaller number of staff clustered within ethno-relative stages and an even smaller cluster within the ethnocentric Polarization stage. The challenge: how to change the conversation to more fully accept the diversity of perspectives, to include them? How to situate these conversations acknowledging the existing cultures, communities, systems and actions of an organization? The value of inclusion has been held for over 40 years in the organization. We knew that providing customized intercultural competence training focused on inclusion was an appropriate and partial approach to changing the conversation for inclusion. We turned to Integral theory, by Ken Wilber and others, particularly the all quadrants component of the AQAL model, as a mapping and organizing tool for engaging with inclusion at NorQuest College.

Looking At Inclusion – A Quadrivia

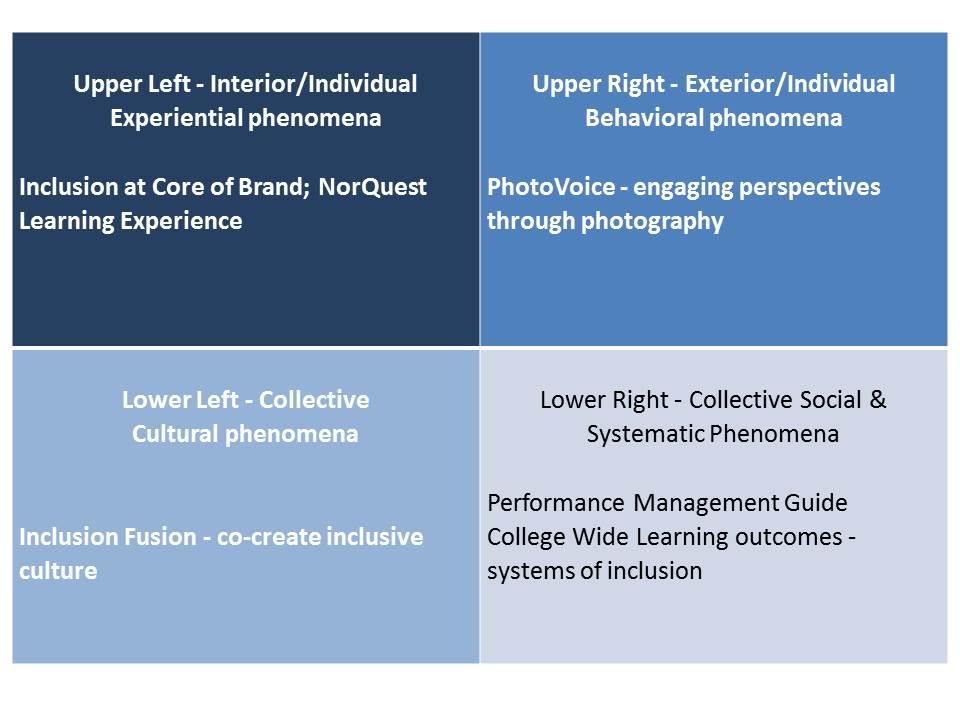

As a mapping tool for Inclusion in the College, we applied the quadrivia lens of the AQAL model. Quadrivia is using the four different perspectives (Singular: I/interior and it/exterior; we/collective interior and its/collective exterior) to contemplate a particular reality, in this case, the phenomenon of inclusion. By contemplating the existing and possible ways inclusion could become present and real at the College, each quadrant provided a lens to see both the presence of inclusion (and exclusion), possible developmental trajectories to grow inclusion and an organizer to choose the focus for action in creating a 5 year strategy to nurture inclusion at the College. “Looking At” inclusion in this way provided an elegant map to place initiatives, current and planned, to nurture inclusion overall at the College.

Mapping Inclusion – Looking At Inclusion

Figure 4. Quadrivia Map: Looking At Inclusion [3]

We agree with Susan Cook-Greuter and Sean Esbjörn-Hargens that this use of the four quadrants is practical and useful as a way to “honor the complexity of reality” such that we could approach the issue of inclusion in a more “skillful and nuanced way” (Cook-Greuter, 2005, p. 77; Esbjörn-Hargens, 2009, p. 7). Cook-Greuter notes, “AQ is powerful because we can choose any topic at any layer of depth in any quadrants and explore it from the other three quadrants to gain a fuller picture and appreciation of its interrelationships (Cook-Greuter, 2005, p. 87). At an organizational level, using a quadrivia view of inclusion, we could look at a co-created reality of inclusion.

Evolution of Inclusion at NorQuest by Quadrant

During the timeframe of the applied research project and in the year following, several activities emerged. Starting in the upper left quadrant, the internally held value of inclusion was re-affirmed and made visible by positioning inclusion as part of the core brand of the College during a re-branding activity led by the College president and the Marketing department. Inclusion is also expressed in the NorQuest Learning Experience policy document. Statements in these policy documents include phrases such as “We embrace diversity and honour inclusiveness” and “Your learning environment embodies diversity. Your uniqueness enriches our college. You will develop skills in cultural understanding to succeed in the global community.” The NorQuest Learning Experience is written from both a student perspective and a College perspective.

Moving to the upper right quadrant, an activity that started as a curricular project, PhotoVoice, became a popular activity that has been repeated by instructors in the years since the project and was added to inclusion training for staff. Briefly, in PhotoVoice, participants are asked to take pictures of inclusion and exclusion, articulating their perspective of what they see in the photo, in their environment, what they think, feel and how they make sense of their community within the College. Sharing their photos and perspectives creates a perspective seeking, intercultural space. Exhibits of these photos, visible artifacts of student generated perspectives have been included in College events like Inclusion Fusion and a permanent installation is housed in central and satellite campus libraries.

Moving to the lower left quadrant, an inclusion culture has been nurtured annually through Inclusion Fusion. The Inclusion Fusion event includes multiple engagement spaces including conversation cafes, the Art of Inclusion, banners to share statements committing to end racism and support inclusion as well as a PhotoVoice display. The event draws students, staff, faculty and community members to share perspectives and engage in community building.[4]

Moving to the lower right quadrant, two systems tools have been generated to support integration of inclusion in curriculum and in professional development. NorQuest uses a system of College wide learning outcomes to identify target learning outcomes for all students and staff. Inclusive Culture outcomes identify various competencies including statements such as “Develop intercultural competencies, including an appreciation for other ways of learning and knowing.” “Challenge personal culture–based assumptions.” “Appreciate how contributions from many people enrich the educational experience and the wider community.” “Demonstrate respect for self and others.” Outcomes at a program and course level are designed to map onto these over-arching outcomes creating linkages between learning activities and learning outcomes. Ongoing curricular development is guided by this outcomes framework.

The Performance Management Guide for Inclusion is structured using existing staff performance tools to suggest ways to embed an inclusion focus into professional development plans and a rubric to rate the level of engagement. Using a five point scale, a one rating relates to a professional learning engagement related to inclusion of a limited duration (e.g. less than 5 hours). Increased learning engagement (e.g. 10-15 hours) is linked to a higher rating (e.g. 3 out of 5). The highest ratings relate to both engaging in a learning activity and applying learning to change something in one’s job, department or functional area in the College to enhance inclusion for others.

The quadrivia view of inclusion supports ongoing monitoring and nurturing of disparate inclusion focused activities and processes. This view supports a connected organizational view linking them directly to institutional performance metrics in ways that address the frequency and duration of engagement as part of the performance metrics. Emerging inclusion initiatives can be added to the overall map of inclusion. From a Center for Intercultural Education perspective, we commit to steward the model to make inclusion more visible at the College, celebrating initiatives that emerge independently of the Center. As we pass through the second academic year since the beginning of the project, we continue to look for indications of emergence within the field of inclusion that is held.

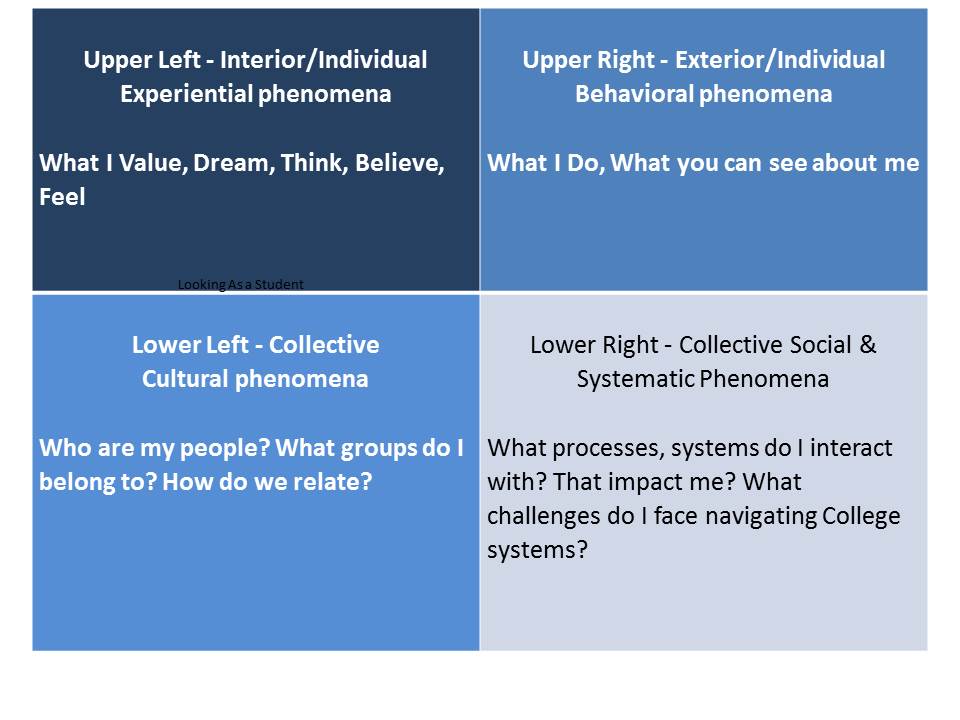

Looking AS: Perspective Seeking as a Doorway into Embodied Inclusion

The AQAL model is described as a framework to organize some of the “most basic repeating patterns of reality” (Esbjörn-Hargens, 2009, p. 2). The quadrants in the AQAL model is one way to depict dimensions or perspectives of reality. In the quadratic approach, the individual is placed at the center of the 4 quadrants, each one representing different aspects of his or her awareness.

Looking As – An Individual Perspective

Looking as a Student

Figure 5: The four quadrants of an individual – doorways into inclusion for a student [5]

Each of these quadrants represents dimensions of an individual’s awareness; this version of the quadrant maps the dimensions of awareness that can be “channels” to take in information from an experience (Esbjörn-Hargens, 2009, p. 7). All individual(s)…”have or possess four perspectives through which or with which they view or touch the world, and those are the quadrants (the view through)” (Wilber 2006, p. 34 cited in Divine, 2009 p. 36). Divine describes the use of quadrants or the view through an individual’s perspective as a way to “look as” the individual in the context of Integral Coaching™. This is an exercise, as much as is possible, to occupy the perspective of another person. In applying the quadrants to “Look As” a student in the context of a student service interaction, we can start to inquire into a student’s perspective of inclusion. As a student or staff member, can I share what I believe and think? Can I connect with others through my values/our values? Are there groups that operate in ways that make sense to me, that feel comfortable to belong to? Will my way of behaving be accepted? Will I get the results I expect when I interact with others? Will I be able to reach my goals as I use and navigate the systems and processes in the College? Can I be successful here and be me?

Intercultural Competence – Qualities to Embody Inclusion

When creating inclusion training or other engagement activities with perspective seeking intent, it became clear that the adoption of the 6 characteristics of intercultural competence used in the Stretch Goal framework were crucial qualities for facilitators of this inclusion engagement space. We needed to embody, to the extent that was possible, the attitudes of respect, openness, and curiosity, to know and learn about cultural self-awareness, and cultural worldviews and to skillfully use verbal and nonverbal communication. These characteristics support us as we hold the space for perspective seeking in a way that honours each individual participating from their unique perspective. We hold the container for participants to make the effort to try on other perspectives including the edges of where and when a person is most challenged by another perspective. Practice of these qualities supported us to hold open the doorway, to invite each person to engage perspective-seeking activities, learning more fully about their own perspective and the perspective of others. An article is under development to articulate more fully the experiences and insights arising from the development and implementation of inclusion training that will explore this approach to perspective-seeking in more depth than is possible here.

Mapping Inclusion as a Living Lens to View Inclusion

The Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model for action is an attempt to use an integrally informed frame to elicit and honor inclusion at NorQuest College at individual, group and organizational levels of analysis and engagement. The model brings together the AQAL model, particularly the all quadrants focus of the AQAL by Ken Wilber and the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity by Dr. Milton Bennett. In this model for action, inclusion is viewed as a perspectival phenomenon and suggests that a socially-constructed culture of inclusion is, in part, based on perspective seeking behaviors and spaces. Out of the applied research project that was used to generate the Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model, one of the products of this attempt was the creation of the Intercultural Competence Stretch Goals document. This document supported the project team to focus more precisely on the developmental edge for inclusion project participants to intentionally serve an organizational shift towards a more ethno-relative perspective of inclusion. As we continue annual activities, the lens provided by the Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model allows us to hold open the questions, What is inclusion? What can it look like? How can we continue to learn from perspectives of inclusion and exclusion? How are we doing? Do our systems and environments support or deter inclusion?

The inclusion interventions that have been implemented since the project have focused on creating opportunities for an embodied perspective-seeking to shift the conversation of inclusion at the College. These interventions have included annual inclusion training for NorQuest staff and faculty, a PhotoVoice curricular activity that allows students to explore inclusion and exclusion through photography and perspective seeking activities; permanent exhibits of the photographs and written perspectives of the student photographers is on display at both central and branch library locations. An annual Inclusion Fusion event held in collaboration with the NorQuest Student Association hosts a variety of perspective-seeking activities such as conversation cafes, the art of inclusion and a PhotoVoice exhibit. The embedding of inclusion as a core College brand has made the internally held value of inclusion visible at the front and center of the College’s public identity. The creating of college wide learning outcomes related to inclusive culture are a tool to integrate inclusion into all college programming as well as to guide faculty and staff professional development. An inclusion-focused performance management resource to support staff and their supervisors to identify both learning and change activities has been created to embed within the College performance management system. At time of writing, other initiatives are emerging such as a student navigator service to support students in navigating College systems.

The quadrivia and quadrant maps of the AQAL model are held as maps to ‘look at’ inclusion across the College and to ‘look as’ each other, to the extent that is possible. These maps allow the Centre for Intercultural Education to steward a living Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model that honors and seeks to understand the emergent inclusion initiatives generated by college community members. We have seen early examples of emergence reflecting only indirect contribution by the Centre for Intercultural Education – the inclusion curriculum outcomes, the Student services navigator initiative, the NorQuest Learning Experience. This author continues to hold open her curiosity and receptivity for what is emerging, checking for signs of both translative and transformational competence gains, through ongoing IDI profile data, and through the quality and frequency of engagement with diversity in the spirit of inclusion within the organization. On a personal note, as a veteran of organizational change initiatives within post-secondary education institutions, the Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model for action has dropped more deeply into the bones of NorQuest College than any of the change initiatives I have participated in or led in the past. Each day, riding the elevators in the College, surrounded by women and men from 87 countries of origin, from First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples, seeing visible physical challenges and sensing into less visible learning challenges, I am privileged to have the opportunity to focus on creating inclusive doorways for every learner, every one that comes to the College. Being included in that work is a good day for me.[6]

References

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2006). Intercultural knowledge and competence value rubric. Retrieved from http://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics/pdf/InterculturalKnowledge.pdf.

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.). Education for the intercultural experience (pp. 21-71). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2004). Making the case for a developmental perspective, Industrial and commercial training, 36(7), 1-9.

Cross, T., Bazron, B., Dennis, K., & Isaacs, M. (1989). Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care, Volume 1. Washington, DC: CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Center for Child Health and Mental Health Policy, Georgetown University Child Development Center.

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization at Institutions of higher education in the United States. Journal of studies in international education, 10(3), 241- 266.

Divine, L. (2009). Look at and looking as the client: The quadrants as a type structure lens. Journal of integral theory and practice, 4(1), 21-40.

Epley, N., & Caruso, E. M. (2009). Perspective taking: Misstepping into others’ shoes. In K. D. Markman, W. M. P. Klein, & J. A. Suhr (Eds.). Handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 295-309). New York: Psychology Press.

Epley, N. Caruso, E.M. & Bazerman, M.H. (2006). When perspective taking increases taking: Reactive egoism in social interaction, Journal of personality and social psychology, 91(5), 872-889.

Esbjörn-Hargens, S. (2009). An Overview of Integral Theory: A Content-Free Framework for the 21st Century. Resource Paper No. 1, Integral Institute.

Ford, J. D. (1999), Organizational change as shifting conversations, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(6), 480-500.

Fuhs, C. (2013). In favor of translation: Researching perspectival growth in organizational leaders. Retrieved from https://foundation.metaintegral.org/sites/default/files/Fuhs_ITC2013.pdf.

Hammer, M. R., Bennett, M. J., & Wiseman, R. (2003). Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27, 421-443.

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

King, P.M. & Baxter-Magolda, M.B. (2005). A developmental model of intercultural maturity. Journal of College Student Development, 46, 571-592.

Pope, R.L., Reynolds, A.L. & Mueller, J.A. (2004). Multicultural competence in student affairs. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

About the Author

Cheryl Whitelaw works as the Applied Research Manager at the NorQuest Center for Intercultural Education in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Growing intercultural competence as an instrument of peace in multicultural Canadian society has been her primary motivation in advancing the Center’s mission. She is a certified Integral Master Coach™ with Integral Coaching Canada and a Credentialed Evaluator with the Canadian Evaluation Society, combining these skills sets as principal of Dagu Integral Services. Cheryl has completed over 40 innovative projects in the field of education, specifically in the areas creating opportunities for learning through technology enhanced learning and intercultural education. She integrates her expertise and experience in service of a non-profit organization dedicated to bringing free learning opportunities to learners facing barriers. She trains in both Pilates and Aikido.

Email: Cheryl.whitelaw@daguintegral.com or Cheryl.whitelaw@norquest.ca Websites: www.daguintegral.com and www.norquest.ca/cie

[1] For the model development, I want to thank Kerry Louw, Center for Intercultural Education, NorQuest College and Meg Salter from MegaSpace Consulting for their willingness in the Inclusive Student Engagement project to grind through the work of combining two theoretical models to reach the simplicity of integration that comes on the other side of that complexity. For a complete listing of collaborators and participants, see the Acknowledgements page in the Inclusive Student Engagement Final Report at http://www.norquest.ca/NorquestCollege/media/pdf/centres/intercultural/ISE/ISEFinalReport_Nov2012.pdf.

[2] It is the author’s intention to write the results of the training program in a separate article with her colleague, Kerry Louw. A discussion of those results will not be included here.

[3] Adapted from Esbjörn-Hargens, 2009, p. 5.

[4] For more information on the activities emerging out of the Inclusion = Diversity + Engagement model, see the Inclusive Student Engagement website at http://www.norquest.ca/norquest-centres/centre-for-intercultural-education/projects/completed-projects/inclusive-student-engagement.aspx.

[5] Adapted from Esbjörn-Hargens, 2009, p. 5.

[6] Special thanks to Laura Divine and Joanne Hunt, co-founders of Integral Coaching Canada. My work has been made possible as a graduate of Integral Coaching Canada. My personal embodied sense of the AQAL as a living legacy of their inspired coaching school and a member of a global community of graduates is core to my commitment to reduce suffering in the name of inclusion at NorQuest College.

Hi Cheryl, I am truly inspired by reading your article on the ‘Inclusion Model’ and I am keenly interested to read more on developing a culture of inclusion in our world today. How to work toward consciously creating to cultivate intercultural competence. Where could I find more research articles and information. Thanks.