Jorge Taborga

Abstract

Jorge Taborga

This essay examines conscious evolution through an integral lens. It presents a perspective on the dilemma of our times focusing on evolutionary responsibility. Evolution is examined from the dimensions of depth and complexity, or subjectivity and objectivity. Frameworks are explored encapsulating human evolution from both of these dimensions. The integral framework is presented as informed by integral theory. Wilber’s integral constructs of All-Quadrants, All-Levels and All-Lines (AQAL), levels and lines of development, states, and types are introduced. The author presents a holon for conscious evolution. This holon is explored for each of its quadrants, and their corresponding levels and lines of development are proposed in the context of conscious evolution. This proposal is presented both from a theoretical and an experiential basis. The author shares his own experiences in his journey toward conscious evolution.

Table of Contents

Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….1

The Dilemma of Our Time…………………………………………………………….. 5

Depth and Complexity………………………………………………………………….. 8

The Integral Framework………………………………………………………………. 20

Levels of Development………………………………………………………………… 25

Lines of Development………………………………………………………………….. 26

States………………………………………………………………………………………… 27

Types…………………………………………………………………………………………..28

The Conscious Evolution Holon…………………………………………………….. 28

Subjective Quadrant…………………………………………………………………….. 29

Subjective Levels of Development………………………………………………….. 31

Subjective Lines of Development……………………………………………………. 34

Behaviors Quadrant……………………………………………………………………… 37

Objectified Levels of Development………………………………………………….. 39

Objectified Lines of Development……………………………………………………. 43

Cultural Quadrant…………………………………………………………………………. 48

Intersubjective Levels of Development…………………………………………….. 50

Intersubjective Lines of Development………………………………………………. 54

Social Quadrant……………………………………………………………………………. 59

Interobjective Levels of Development………………………………………………. 60

Interobjective Lines of Development………………………………………………… 63

Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………. 71

References…………………………………………………………………………………… 74

Introduction

Evolution is a constant in the human experience, although we interpret it in different manners. To some, particularly science, evolution is an accidental progression that yielded the cosmos, our planet and life. To others, it is a process created by a supreme being as part of a master plan. Regardless of our beliefs, life in the universe evolves with new stars being born, galaxies forming, and life on planet Earth continuing in a constant state of flux.

According to scientific analysis, the evolution of the universe started with the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago and will continue for an indefinite period of time (Alles, 2010). We humans are as much a part of this cosmic evolution as any galaxy or star. Even with the increasing sophistication of scientific methods and tools, we cannot predict where evolution will take us. It is not clear if our degree of evolution on Earth is the most evolved in the universe and if it can continue further. What is certain is that we as a species are changing and that to a large degree, we have control of what happens to life on Earth (Banathy, 2000).

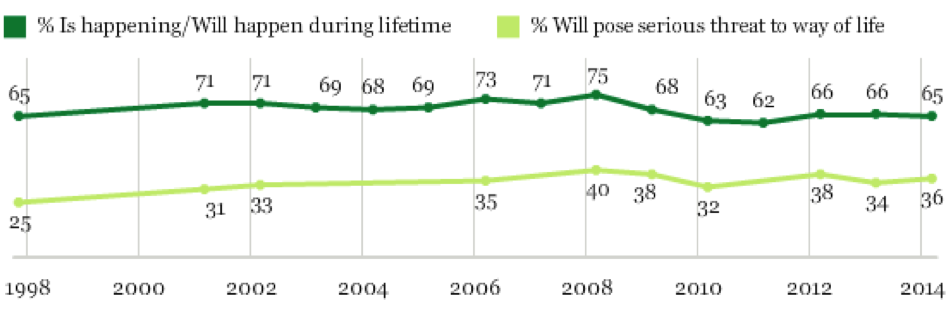

There is significant debate about the sustainability of our planet (Schor & Taylor, 2003). Driven by scientific evidence, some adhere to the notion that Earth is a planet in peril. Others deny this notion and sustain that life will continue its course and that humans do not need to worry. Global warming has been identified as one of the threats to sustainability (Letcher, 2009). Figure 1 shows the multi-year results of a survey about global warming. In it, only 36% of those surveyed currently believe that global warming is an issue we should worry about.

Figure 1. Gallup poll on global warming (Jones, 2014). The question asked in the survey was, “Do you think that global warming will pose a serious threat to you or your way of life in your lifetime?”

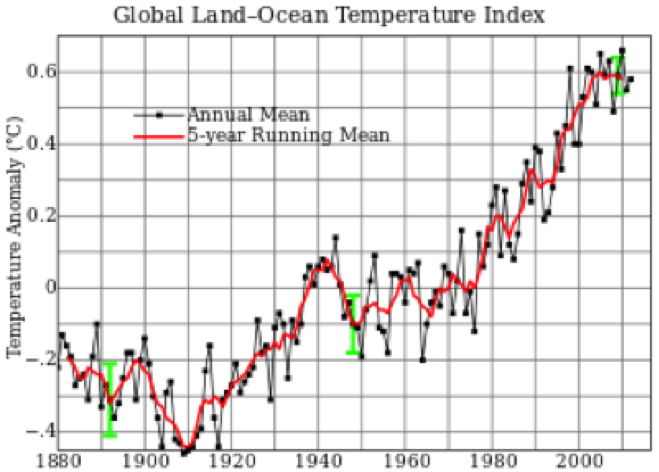

In contrast to the results of the survey in Figure 1, scientists are 95% to 100% certain that increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases produced by human activity such as the burning of fossil fuel and deforestation are contributing to global warming (Letcher, 2009). Figure 2 shows the increase in temperature on Earth since the 19th century.

Figure 2. Global Land-Ocean temperature index (Earth: The operator’s manual, 2014). This graph shows the increase in temperature by about one degree Celsius since the start of the 20th century.

Figure 2. Global Land-Ocean temperature index (Earth: The operator’s manual, 2014). This graph shows the increase in temperature by about one degree Celsius since the start of the 20th century.

Aside from global warning, there are other pressing issues related to our sustainability. Water and food shortages are becoming more prevalent due to increasing population (Hulme, 2013). Deforestation not only contributes to global warming but also to atmospheric and hydrological, soil erosion, and biodiversity loss. Along with impact to human life, we are also experiencing dramatic species extinction (Hulme, 2013). Over a thousand species have disappeared over the last 500 years (Center for Biological Diversity, 2014).

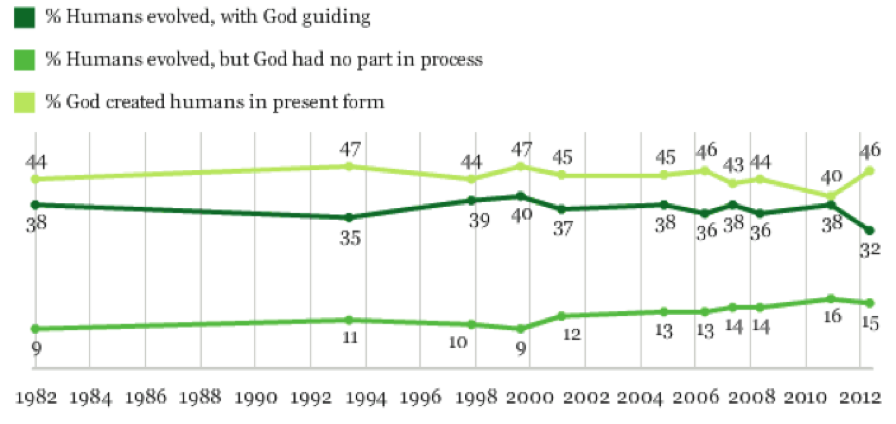

The large discrepancy between the facts of our planet being in peril and the response from Earth’s inhabitants to it point to significant differences in the understanding of evolution. It is hard to conceptualize that anyone who has internalized how life came to being in the 13.8‑billion-year cosmic journey would be apathetic to the sustainability challenges we are experiencing. Figure 3, also a Gallup survey, shows differences in cosmological understanding.

Figure 3. Gallup survey over the last 30 years showing the cosmology perspective of those surveyed in the United States (Evolution, Creationism, and Intelligent Design, 2014). The survey asked the following question: “Which of the following statements comes closest to your views on the origin and development of human beings: a) human beings have developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but guided this process; b) human beings have developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God had no part in this process, or c) God created human beings pretty much in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years or so?”

The graph in Figure 3 shows that 46% of those surveyed in the United States believe that God created humans in their present form in the last 10,000 years or so. That notion completely negates the main tenants of cosmic evolution. My first reaction to this data was that perhaps the 46% corresponded to mostly uneducated people. This notion was somewhat invalidated in conversations I had with highly educated individuals in my workplace who sustain that humans were created in their present form, and no more than 10,000 years ago.

This essay will make a case that a certain level of development (maturity) in terms of subjective and objective experiences is necessary for someone to connect with our evolutionary reality and have appreciation for it. This appreciation translates into not only the recognition of where evolution has brought us but what we need to do in order to actively participate in it. The solution to the problems of our planet may entirely rest in the hands of the individuals who have reached a level of maturity needed to connect with evolution itself.

Integral theory will be used as the lens to present the case. The integral theoretical framework places a person at the center of its subjective and objective experience both in individual and collective contexts. Given that the integral lens is completely experiential (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010), I will bring my own evolutionary experience into the core of the essay, understanding the risks of balancing academic research with subjectivity. In this fashion, this essay aims to build an intersubjective reality with the reader.

I submit that conscious evolution is a personal journey, and it is necessary to make meaning of it (internalize it) before it makes sense. Over the last 30 years, a meta-discipline has emerged on the subject of conscious evolution, which is the output of the personal evolutionary journey of a number of luminaries. Its main purpose is to identify and develop a path to a sustainable planetary future based on the concept that human evolution can be guided. The proponents and contributors to this meta-discipline—such as Bela H. Banathy, David Bohm, Eric Chaisson, Duane Elgin, Erich Jantsch, Ervin Laszlo, Brian Swimme, Ken Wilber, and Barbara Hubbard—define and describe a developmental path that we can deliberately establish, resulting in an consciousness shift similar to when we gained awareness of self over 50,000 years ago (Banathy, 2003b). Social scientist Bela Banathy summarized the intent of the conscious evolution meta-discipline with the following statements:

The right of people to guide their destiny; to take part directly in decisions affecting their lives; to create healthy, authentic, and nurturing evolutionary communities; and to control their resources and govern themselves is a most fundamental human right. If people learn how to exercise this right, then they have the power to create a civil society, a true democracy, in which they can design their own lives, participate in the evolutionary design of the systems in which they live and work, and organize their individual and collective lives in the service of the common goal. (Banathy, 2000, p. 2)

The Dilemma of Our Time

Our history is plagued with end-of-the-world scenarios. Our documented doomsday prophecies date as far back as 634 BCE, when many Romans believed that the city would be destroyed in the 120th anniversary of its founding (Vacker, 2012). The latest predictions about the end of the world were associated with the Mayan calendar that pointed at the year 2012 as the end of times (Vacker, 2012). I provide these references because I worry that our scientific predictions about climate change, water scarcity, and other modern complications may simply be more sophisticated “end-of-the-world” predictions backed by scientific observations that may be based on narrow perspectives.

In my mind, we should not embrace an evolutionary consciousness only because of the possibility of a large impact to life in our planet. We should do so because we understand the enormity of evolution itself and that at this point in our development we have influence in what happens next to our species, other species on Earth, and perhaps the planet itself.

To gain a deeper appreciation for where we are in our planet’s evolution, it is important to understand climate changes and levels of carbon dioxide. Both of these conditions significantly affect life (Letcher, 2009). Climate change has been part of our planet’s history. There have been five major ice ages in the 4.7 billion years since the formation of Earth (Woodward, 2014). We are currently in the Quaternary glaciation that started 2.58 million years ago. Within each ice age, we experience cycles of glaciation with ice sheets advancing and retreating on 40,000- and 100,000-year time scales called glacial and interglacial periods.

Earth is currently in an interglacial period (Woodward, 2014). The last glacial period ended about 10,000 years ago. All that remains of the continental ice sheets are Greenland and Antarctic and smaller glaciers such as the ones on Baffin Island (Woodward, 2014). Population development greatly advanced in the last 10,000 years from an estimated 1 million inhabitants to our current level of nearly 7 billion humans. This growth was made possible by many technological advances, but having a warmer planet was a significant condition.

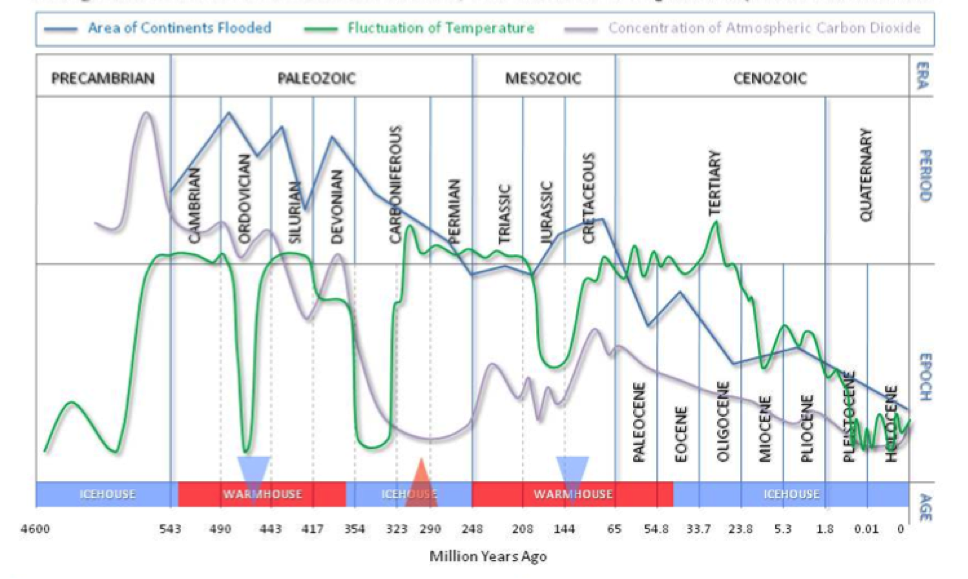

Figure 4 shows three superimposed graphs of the amount of flooding, the fluctuation in temperature, and the concentration of carbon dioxide in our planet across eras from the Precambrian to the current Cenozoic. In this figure, we can graphically appreciate that in our current epoch (Holocene), we have the greatest amount of inhabitable landmass, the least amount of temperature fluctuation, and the least concentration of carbon dioxide. These three conditions have not previously occurred in the history of Earth. We are living in a unique period of geological wonder. This alone makes our current life conditions miraculous regardless of any cosmological belief. Whether God architected the life conditions we now enjoy or had nothing to do with them, we live in very special times that have taken 4.7 billion years to reach.

Figure 4. Life condition markers across Earth’s eras (Nahle, 2007).

From the information in Figure 4, we can discern that the dilemma of our times is not so much temperature or carbon dioxide because both have widely varied and have been at unsustainable levels to support life before. I believe the dilemma we face has do to with providing dignified life conditions to our large population, the harmonious coexistence with the remaining species, and maintaining our natural environment with as much life-sustaining capability as possible for as long as we can. After all, we know from geology that at some point life conditions will drastically change as we return to another ice age (Woodward, 2014).

I do not believe we have the power to affect cosmic evolution, including what happens to our planet in the long run. Our own sun—a star—will cease to exist in approximately 6 billion years (Cain, 2012). This seems like an eternity to worry about in anyone’s lifetime. However, I go back to how precious life is in the present moment considering all that had to take place since the Big Bang for us to enjoy a cup of coffee at Starbucks. What is sad about our human evolution is that not everyone can enjoy that cup of coffee; and this is where the opportunity lies. We can consciously evolve as a species taking care of all humans, other species, and our home planet

Depth and Complexity

At the heart of evolution are depth and complexity. Depth refers to our subjective and intersubjective development, the degree of consciousness we exhibit individually and collectively (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). Complexity is associated with our physical reality, which has advanced from the moment two hydrogen atoms combined to form helium to our sophisticated technologies and social environments. This section explores the evolutionary aspects of our physicality (complexity) and our psychic and cultural evolution (depth).

Our evolutionary history starts with the Big Bang, estimated to have taken place 13.8 billion years ago (Alles, 2010). From the Big Bang, about 400 million years transpired before atomic structures necessary for the formation of stars manifested and about a billion years to the start of the first galaxies. Our current universe developed in the subsequent 13 billion years. About 4.6 billion years ago, our solar system was originated and, with it, our planet. Life on Earth started 3.8 billion years later, and our research shows that humanoids—our ancestors—surfaced around 7 million years ago (Banathy 2000; Banathy, 2003b; Alles, 2010).

As astrophysicist Eric Chaisson (2005a, 2005b) stated, evolution seems to be wired into the DNA of the universe. Chaisson posited that no matter what we do, the universe continues to expand and change. Seventy-two percent of the known universe is composed of dark energy (Alles, 2010). We understand very little what this dark energy does or where it comes from. What we do know is that it is the force responsible for the expansion of the universe. It acts as an anti-gravitational force that pushes the universe to seek new order in the formation of additional stellar structures.

We do not know where the cosmic evolutionary process is headed. There is even scientific evidence that our universe may not be the only one in existence (Chaisson, 2005a). What we do know is that evolution moves us into higher levels of complexity. Chaisson (2005b) studied this phenomenon particularly in relationship to entropy. This second law of thermodynamics tells us that disorder is the natural state of things, and it takes energy to create order. A planet requires more order than a star, and a star requires more order than a galaxy to exist. Consequently, evolution requires higher rates of energy to create and sustain newer structures.

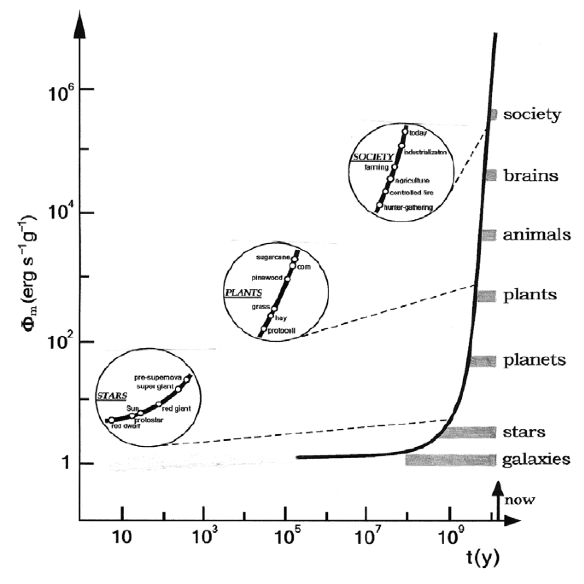

Chaisson (2005b, 2010) developed a measure of the rate of energy required to sustain higher levels of evolution. He conceived this measure in units or erg/second/gram and called it energy-rate-density. It measures the amount of energy flow through a given mass. Higher order structures like the human body require a much larger amount of energy-rate-density to keep it together than a star. Figure 5 shows Chaisson’s evolutionary timeline for complexity as measured by energy-rate-density.

Figure 5. Evolution timetable measured in energy-rate-density units of erg/second/gram (Chaisson, 2005a, 2005b). The evolution timeline is in increments of 10 million years. The evolution of life on Earth took place over the last one billion years with society originating about 50,000 years.

Figure 5 shows that the amount of energy-rate-density to hold a galaxy together has a value of “1” erg/second/gram in contrast with society that registers close to 1 million of the same units. This figure makes the case for the increasing levels of complexity as evolution moves into higher levels of structures and the requirement for more energy to keep it together.

Chaisson (2005b, 2010) divided our evolutionary history into three eras: Energy, Matter and Life. He stated that we are now entering the Life Era even though we have had life on Earth for the last 4 billion years. However, he posited that for the first time in our evolutionary history, life is more dominant than matter (Chaisson, 2005b). Chaisson (2005b) also pointed to the fact that we are evolving at a much higher rate than our natural environment. This astrophysicist surmised that we have to change our way of living and adapt to the natural Earth environment, or we have to build synthetic environments to sustain our way of living, including food. As Chaisson remarked, our role in the Life Era is one of co-creation.

Humans physically evolved into the homo-sapiens-sapiens (HSS) and started to advance culturally only in the last 50,000 years (Banathy, 2003b). Table 1 provides a summary of the cultural advancement characteristics defined by paleoanthropologist Rick Potts and covered in Banathy’s (2000) Guided Evolution of Society: A Systems View. This table was used by Banathy to describe the cultural evolution of the leading to the HSS.

Table 1: Cultural Advancement Definitions by Rick Potts Synthesized from Banathy (2000)

| Cultural Advancement | Definition |

| Transmission | Transfer of information between individuals. Higher level of transfer requires more social encounters. |

| Memory | Retain information to which the person was exposed. |

| Reiteration | Tendency to reproduce or imitate stored behaviors or transmitted information |

| Innovation | Capacity to alter transmitted information or generate new as a result of the development of new skills or variations |

| Selection | Process by which a social group blocks or filters certain innovations and maintains others |

| Symbolic Coding | Ability to develop and use language/communication that can be used by others |

| Institutions | Association containers with specific cultural functions |

Using the definitions in Table 1, we can construct an evolutionary lens into the cultural advancements of the precursors to the HSS. Table 2 shows how each major humanoid was limited in its advancement and required the next form to acquire higher cultural characteristics. For instance, the Archaics survived and gave birth to modern humans, the HSS. They were able to achieve symbolic coding given their longer larynx that enabled them to speak, in contrast to the shorter one of the Neanderthals that limited their ability to verbally communicate (Banathy, 2000). In addition, the Archaics were able to perform selection, improving their ability to adapt and use tools. In contrast, the Neanderthals left their tools behind when they relocated and had to rebuild them at the next location (Banathy, 2000). They could not “select” and change what their ancestors did before. The Neanderthals’ limited selection and absence of symbolic coding may have contributed to the disappearance of this humanoid species.

Table 2: Cultural Advancement for the Major Humanoid Species

| Cultural Advancement | Afrensis4M | Africanus3M | Habilis2.5M | Erectus2M | Neanderthal0.5M | Archaics1M | Human35K | |

| Transmission | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Memory | Limited | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Reiteration | Limited | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Innovation | Limited | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Selection | Limited | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Symbolic Coding | Limited | Yes | ||||||

| Institutions | Yes |

Note: This table is an adaptation and synthesis of the human evolution narrative in Banathy (2000) using the cultural advancement definition by Rick Potts.

Banathy (2000, 2003b) introduced the concept of four generations of modern humans. The first—the Cro-Magnon—is only 50,000 years old. The Cro-Magnons were the first humans to develop self-awareness. Their predecessors—humanoids, early homo-sapiens, and Neanderthals—did not have a consciousness distinct from their environment. During the 7 million years that the humanoid form graced this Earth, consciousness was a dreamlike state that was undifferentiated from nature. This dreamlike state of consciousness changed and acquired self-identification when the homo-sapiens-sapiens, or Cro-Magnon, burst into the evolutionary scene around the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic era (Banathy, 2000). Their consciousness model was magical, sensory based, capable of reflection, and focused on “today.” Cro-Magnons lived in tribes and manufactured a number of tools, primarily for hunting (Banathy, 2000). It took another 25,000 years or so for them to develop into the second generation of humans with the advent of agriculture.

The Agrarian Age emerged about 12,000 years ago (Alles, 2010). It started with agricultural villages developing into the big cities of the Hellenic period followed by the Byzantine and Roman empires. This Age ended with the decline of civilizations in the Dark Ages. At the start of the Agrarian Age, collective consciousness shifted from a magical to a mythical context. Also, the mostly sensory reflectivity developed into emotional. The “live-in-the-present” focus of the Cro-Magnons evolved into one of planning and preparation for future events, such as the harvest, storing food, and building edifices (Banathy, 2000). Language played a key role in the development of this second generation human. Spiritually, Mother Earth was the center of attention, and rituals correlated to the need for rain, crop, and protection from the elements.

The second generation of humans is responsible for building our ancient civilizations from Mesopotamia, to Greece, to Egypt, and to Rome, and the ones in Asia and South America (Banathy, 2000). A new myth emerged in these civilizations based on the separation of the sky and Earth. This precipitated the concept of heaven and a God that lives in the skies. Writing allowed these civilizations to perpetuate their knowledge and make it available to the next generations. Technology evolved allowing them to build and become more efficient in their work endeavors.

The third generation of humans entered the scene at the end of the Middle Ages (Banathy, 2003b). It was the Renaissance that gave birth to our current human generation. This era has been called The Age of Enlightenment, the Age of Reason, and the Age of Science and Technology. This age brought (a) a new level of consciousness: mental consciousness; (b) the printed word, which became a new mode of mass communication evolving into our connected social media; (c) scientific pursuits leading to today’s technological advances; (d) industrial/ machine technology; and (e) capitalism (Banathy, 2000). Nation states became the social structures for third-generation humans, and technological development exploded into a multitude of directions. The third-generation human gained—for the first time—control of life.

From a human complexity perspective, we are at the portal of what Banathy called the “fourth generation” human (2003b). According to Banathy, what distinguishes this fourth generation from its predecessors is evolutionary consciousness. He also posited that we are the first generation of humans that have access to concrete information regarding the human trajectory and the knowledge of where this trajectory can lead (Banathy, 2003b).

Table 3 recaps the cultural advancement of Banathy’s four generations of humans using the Rick Potts framework. Banathy placed the inception of the fourth generation in current time. The characteristics corresponding to this generation in Table 3 are to some degree speculative.

Table 3: The Cultural Advancement for the Four Human Generations

| Cultural Advancement | First GenerationCro-Magnons35K – 10K | Second GenerationAgriculture / Ancient Civilizations10K – 0.5K | Third GenerationScientific Industrial0.5K – today | Fourth GenerationEmergingToday – Future | |

| Consciousness | Magical, reflective, sensory | Mythical, reflective, emotional | Rational, reflective, mental | Reflective, spiritual, ethical | |

| Transmission | One-to-one | One-to-many | Many-to-many | Any-to-any | |

| Memory | Simple concepts | Simple to Complicated | Complicated to Complex | Complex | |

| Reiteration | Within tribe | Within community | Within nation to global | Global | |

| Innovation | Tools | Agriculture, metal | Industry, electricity, electronic communication | Sustainable technologies, renewable energy | |

| Selection | Family and Tribe | Community | Nations and some worldwide | Global community | |

| Symbolic Coding | Oral | Written | Print, Multi-media | Rich-media, social media | |

| Institutions | Tribes | Ancient civilizations | Nation states | Global Federation | |

Note: This table is an adaptation from the information in Banathy (2000, 2003b).

Banathy (2000, 2003a, 2003b) stated that we are at the threshold of the emergence of our next evolutionary event. This event, he said, is marked by “conscious evolution, the self-guided emergence of the fourth generation of homo-sapiens-sapiens” (Banathy, 2003b, p. 313). The social scientist specified a number of markers that point to this threshold based on the evolutionary events that have preceded our three generations of humans.

Undoubtedly, our universe, our planet, and we have evolved in complexity since the Big Bang. Human development has accelerated since the time of the Cro-Magnons 50,000 years ago. But how about our subjective development, our depth? How do we understand our internal development both individually and collectively? This is a challenge that Graves undertook with his research as primarily documented in Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change (Beck & Cowan, 1996) and The Never Ending Quest (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005).

Through his research, Graves developed the Emergent Cyclical Levels of Existence Theory (ECLET) from the data he initially collected from 1952 to 1959 regarding the personality of the mature adult in operation and his extensive follow-up with his subjects (Lee, 2009). His researched yielded the following evolutionary psychic patterns:

- Expressing self impulsively at any cost—changing to

- Denying/sacrificing self for reward later—changing to

- Expressing self in calculating fashion and at the expense of others—changing to

- Denying/sacrificing self now for getting acceptance now—changing to

- Expressing self as self desires but not at the expense of other

There was a sixth classification that Graves noted in the transitions as individuals evolved in depth. This group was another deny/sacrifice self that evolved from the last express-self group that focused entirely on existential realities. It is at this point and throughout the 1960s that Graves developed and matured ECLET. His conclusion was that his classifications represented the amalgamation of unique life conditions and mind capacities (internalities) that form part of human evolution. The life conditions present the collection of problems that individuals need to solve, while the mind conditions correspond to the problem-solving neurology (psychic abilities) currently active in each individual. The recorded evolution from one group to the next had to do not only with a change in life conditions (new problems) but an internal transformation that readied the individual to operate at the new level.

As Graves prepared his first set of essays on ECLET, he added two entry-level classifications that preceded the first one he found, express self impulsively (Lee, 2009). In ECLET, Graves theorized that humans evolved from primitive humans to contemporary beings not just physically but socially and psychologically through what he concluded were eight levels of human existence combining life conditions with mind capacities. In his theories, Graves posited that the first six levels of human evolution are fixated on issues of subsistence ranging from physiological survival to mastery of materialism. The last two systems, he viewed, function at a higher octave repeating the basic patterns of the first six but operating at a level of existence no longer preoccupied with subsistence but rather focused on the higher purposes of being human.

Graves utilized a simple notation to refer to the eight value systems in ECLET. He used the letters A through H to represent the life conditions and the letters N through U to denote mind capacities. The pairing of the two letter sequences identifies each of the eight value systems. These are: A-N, B-O, C-P, D-Q, E-R, F-S, G-T and H-U. Using D-Q as an example, this is the sacrifice self for reward later level which has “D” life conditions or problems and “Q” mind capacities to solve them.

Graves conceived that humans evolve from A-N to H-U and beyond. However, he also found in his research that given harsh life condition changes, humans could regress to a lower level (Lee, 2009). Additionally, humans could enter or exist in an environment that is different from their mind capacities. For instance, humans with “R” mind capacities could be in a system with “D” life conditions. ECLET conceives mind conditions to be nested or accumulative. A person with “R” mind capacities has the neurology and psychic ability to understand and operate in any system ranging from A through E. Graves theorized that most humans operate in a combination of a sacrifice and express-self mind conditions (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). His research showed that a small number of people operate in a single-mind condition system. He termed this rare mature adult in operation “nodal.”

According to ECLET, human beings transition from one system to the next when a number of conditions are met that result in a “higher level of neurological direction of behavior” (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008, p. 43). Graves identified six conditions necessary for the transition (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005). The first is the potential in the brain. Unless impaired, the potential for all systems exists in the human brain. Second, the individual should have resolved the existential problems in the current system. Third, a dissonance associated with the breakdown in the solutions at the current level must occur. Graves found that all individuals making a system transition do so after a period of crisis and actual regression. The fourth condition, and the one responsible for stopping the regressive process, is insight. This condition involves having insight into the new ways of solving problems. The next condition, the fifth, is overcoming barriers, including relationships and other constraints. Most relationships ground humans in one system and provide resistance for an individual to move on (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). Consolidation is the sixth and final condition. It involves the practice and affirmation of the new way of solving problems.

To make Graves’ levels of evolution more accessible to the general public, author Chris Cowan devised a color scheme to replace the A-H and N-U letter nomenclature (Cowan & Todorovic, 2008). The colors denote only the “nodal” state of a system, not its life condition/mind capacity pairing. Table 4 provides the key attributes of the eight value system in ECLET.

Table 4: The Eight Value systems in ECLET

| Value System | Spiral Dynamics | Thinking | Motivation | Means/End Values | Problem of Existence |

| A-N | Beige | Automatic | Physiological | Purely reactive | Maintaining physical stability |

| B-O | Purple | Autistic | Assurance | Traditionalism/safety | Achievement of relative safety |

| C-P | Red | Egocentric | Independence | Exploitation/power | Living with self-awareness |

| D-Q | Blue | Absolutistic | Peace of mind | Sacrifice/salvation | Achieving ever-lasting peace of mind |

| E-R | Orange | Multiplistic | Competency | Scientific/materialism | Conquering the physical universe |

| F-S | Green | Relativistic | Affiliation | Sociocentry/community | Living with all humans |

| G-T | Yellow | Systemic | Existence | Accepting/existence | Instilling sustainability in the planet |

| H-U | Turquoise | Differential | Experience | Experiencing/communion | Accepting existential dichotomies |

Note: This table adds the color correspondence introduced by Beck and Cowan in their book, Spiral Dynamics. The contents of this table are based on the article “Human Nature Prepares for a Momentous Leap” published by The Futurist in 1974 (pp. 72-87) and reprinted in Cowan and Todorovic (2008).

The ECLET framework in its popularized form of Spiral Dynamics is widely used to understand and work with social groups of all types, including nations. It is an evolutionary lens with the capability of assisting with our role of co-creators. Following the definitions of each level in ECLET, the Yellow value system has been identified as the most likely source of fourth generation humans (Wilber, 2000; McIntosh, 2007). The Yellow mind capacities seem to be in alignment with the notion of looking at life at a cosmic level and understanding all other mind capacities and life conditions without prejudice. It follows that the work of these Yellow-minded individuals collaborating with all other levels of consciousness would result in the unfolding of the Life Era with the consideration for all of life and the embodiment of our role as co-creators (Chaisson, 2010).

The Integral Framework

The word integral means comprehensive, inclusive, non-marginalizing, and embracing (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). An integral approach to any field aims to include as many perspectives, styles, and methodologies as possible within a coherent view of the topic (Wilber 2000, 2011). As mentioned in the introduction, I am using integral theory as the lens to describe my relationship with conscious evolution. Integral theory explores phenomena from subjective and objective perspectives, both at individual and collective contexts (Cacioppe & Edwards, 2005; Edwards 2005; Wilber 1997, 2000, 2011). As addressed in the previous section, the subjective experience corresponds to evolutionary depth and the objective to evolutionary complexity. This section introduces the integral framework and its connection to evolution.

Koestler (1990) introduced the term holon in his book titled The Ghost in the Machine. The word holon is derived from a combination of the Greek holos, meaning whole, and the suffix on, suggesting a particle or a part, as in proton or neutron. In this definition, a holon is both a whole and a part and can be described in terms of its holistic and independent nature, as well as its dependent and interconnected components. Koestler envisioned that holons exist in a nested hierarchy, which he called holarchy (Edwards 2005). A holarchy differs from the more common network hierarchy in that the holarchy is an encapsulating construct, not just relational, as is a network. Holons exist within holons, which in turn live inside larger holons.

Koestler’s (1990) work with holons was motivated by his desire to establish a bridge between the Newtonian, or mechanistic, worldview, which places importance in the parts of a system, and a holistic view, which downplays the parts in favor of the whole (Wilber 2000). He also recognized the importance of the evolutionary process in social systems. Koestler sought to define a framework to understand social systems, which provide a balance between the micro‑level of individuality and the macro-level of collectivity.

Philosopher Ken Wilber, building upon Koestler’s holonic construct that defined an individual and a collective reality, added the concept that a holon also has an interior or subjective reality, and an exterior or objective reality (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). Wilber further extended Koestler’s construct in the articulation of the evolutionary properties of a holon, defined as stages and lines of development. Further, he articulated the premise that a holon co‑evolves through stages of development via synergistic integration of its individual-collective and interior-exterior realities (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010; Edwards, 2005). Wilber’s stages of development synthesize the research of developmental psychologists including Piaget, Lovinger, Kegan, and Graves. For Wilber, lines of development are the capacities we need to master to solve the problems we face at each stage of development. This is consistent on how Graves conceptualized the stages in ECLET as a duple of life conditions and mind capacities (Merry, 2009).

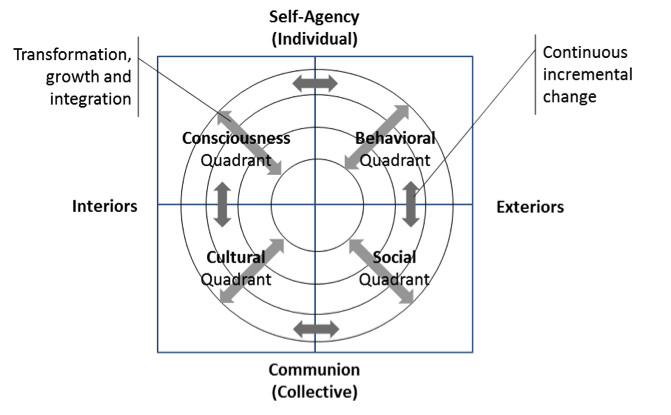

Wilber introduced the integral framework to articulate the “fundamental domains in which change and development occur” (Edwards, 2005, p. 272). Wilber’s integral theory proposed that social phenomenon requires the consideration of at least two dimensions of existence: (a) interior-exterior, and (b) individual-collective (Wilber, 2000). The interior-exterior dimension corresponds to the subjective/reflective experience in relationship to the objective or behavior-based reality. In the second dimension, the individual-collective refers to the relationship of the experience of self-agency and that of community. The All-Quadrants, All‑Levels framework is represented as a 2 x 2 matrix demarcated by these two dimensions. Figure 6 shows this framework, its dimensions, and the definition of the resulting four quadrants.

Figure 6. This framework, an adaptation of Edwards (2005), shows the four organizational quadrants formed by the two existence dimensions of interior-exterior and individual-collective. The shaded arrows correspond to the dynamics inside the dimensions. The short vertical and horizontal lines represent the continuous and incremental changes that take place in life. The diagonal arrows correspond to developmental levels that denote transformational changes, typically associated with growth and integration.

In the framework shown in Figure 6, the upper left quadrant corresponds to the consciousness of individuals. This reflects their level of awareness, how they make meaning of life, how they interact with others, their beliefs, values, and intentions (Wilber, 2000). This is the internal world of individuals. According to Wilber and others, across the millennia and particularly over the last 50,000 years, we have evolved from an archaic/animistic idea of self to one that is more holistic and integral to the whole of life (Wilber, 2000; Edwards, 2005, Lee, 2009).

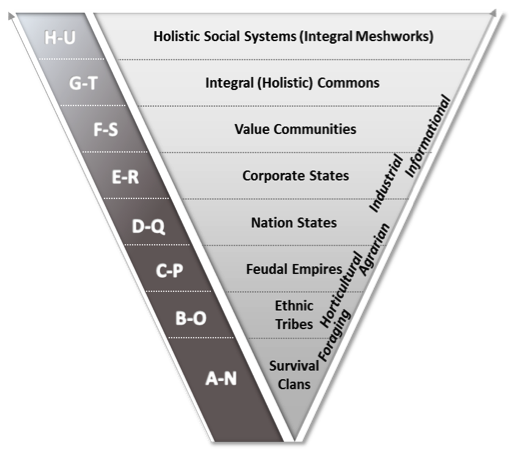

The cultural quadrant represents our evolution as a human collective (Edwards, 2005). Over 50,000 years ago, we did not have the idea of the “I” and the “you.” As these ideas came into being, the “we” was manifested, and with it we evolved into the sophisticated societies populating our planet today. We moved from clan life, to tribes, to power-controlled societies; then, we continued to evolve into absolutistic thinking, giving way to modernism, postmodernism, and now an integral way of relating (Lee, 2009).

The upper right quadrant corresponds to the behaviors, skills, and knowledge that form our daily lives. This quadrant evolved with our cells; bodies; brain; and cognitive functions leading to practices like leadership, systems thinking, design thinking, and emergence (Wilber, 2000). The evolutionary path in this quadrant has followed millions of years. Our social capabilities and sophistication in this quadrant have accelerated in the last hundred years. Technology has played a key role in this acceleration (Chaisson, 2010).

The final quadrant depicted in Figure 6 is associated with our social development, in particular, with our social systems (Edwards, 2005). Our foraging beginning as clans and tribes developed into horticulture and later agriculture as our collectives moved from tribes to more organized systems. These early systems gave way to technology and trade, making agriculture a vital part of our societies. Evolution continued into the industrial and later the information age with advances into every facet of our lives. Our social systems developed from simple tribal organizations to the sophisticated global entities we have today.

Integral theory posits that we cannot understand any of the realities depicted by any one quadrant through the lens of any of the others (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). All four quadrants are required to completely represent and understand any phenomenon. Unlike other approaches to meaning-making that may want to reduce phenomena to a purely subjective or objective reality, or a purely individual or collective experience, integral theory understands each quadrant as simultaneously arising (co-evolving). This is the connection that the integral framework has with depth and complexity development.

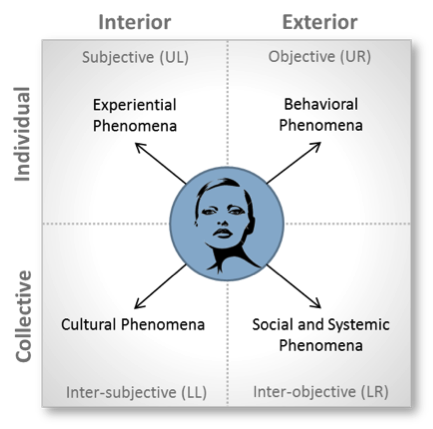

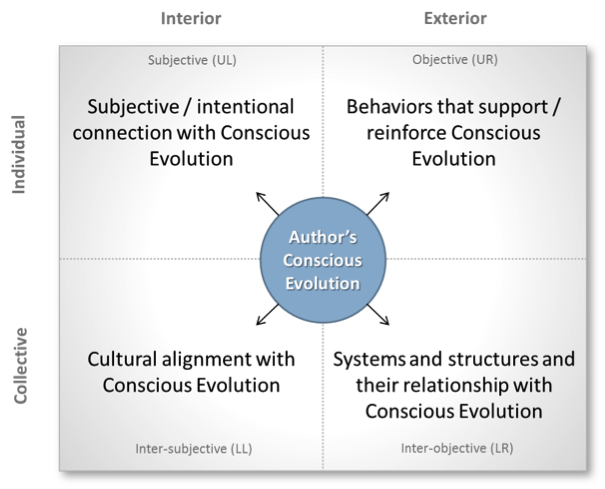

There are two approaches that integral theory provides to explore a phenomenon: quadratic and quadrivia (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010; Wilber, 2011). The first—the quadratic approach—depicts an individual situated in the center of the quadrants. The arrows point from the individual toward the various realities that he or she can perceive as a result of his or her own embodied awareness. Figure 7 illustrates the quadratic approach to meaning-making.

Figure 7. The quadrant representation for a quadratic inquiry to a given phenomenon (Esbjorn‑Hargens, 2010).

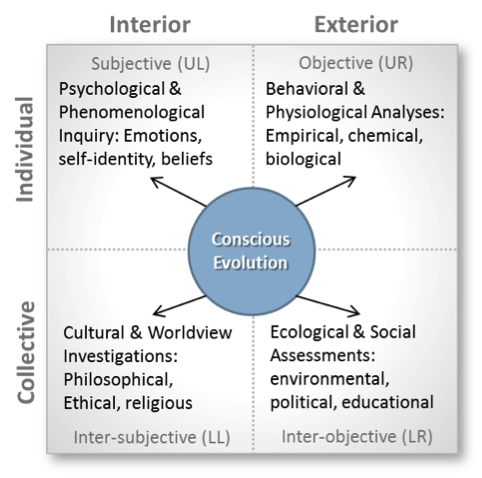

The second approach to pursue the understanding of a phenomenon is known as quadrivia. This approach refers to four distinct ways of meaning making (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). In quadrivia, the different perspectives associated with each quadrant are directed at a particular reality, which is placed at the center of the quadrants. Figure 8 shows the quadrant representation in the quadrivia approach. For this essay, I am embracing the quadratic form of inquiry on conscious evolution.

Figure 8. The quadrant representation for a quadrivia inquiry to a given phenomenon (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). This figure shows conscious evolution as the subject of the inquiry and four different methods of inquiry, one for each quadrant.

Aside from the quadrants, the integral framework as defined by Wilber consists of four additional constructs: (a) levels of development, (b) lines of development, (c) states, and (d) types.

Levels of Development

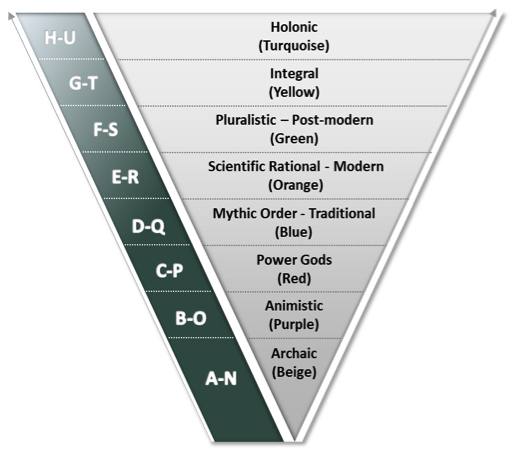

Within each quadrant there are levels of development that correspond to increasing depth and complexity (Wilber 2000). As stated previously, depth is associated with both individual and collective subjectivity, while complexity corresponds to the external reality, also at the individual and collective dimensions. Levels at each quadrant can be understood as waves of probability representing the dynamic nature of reality and how this reality is manifested under certain conditions (Wilber 2000, 2011). Graves defined levels (stages) as life conditions that have evolved as humans gained consciousness from the A-N stage (Beige) to the H-U stage (Turquoise).

The levels of each quadrant provide the map to the life conditions within it. These life conditions co-evolve (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). As an example, the cultural quadrant level of E-R (Orange) has led to entrepreneurship, which has produced advances in technology, a physical manifestation in both the upper-right and lower-right quadrants. As we interact with technology in those quadrants and apply it to social systems, our culture (intersubjective reality) is impacted and continues to evolve. Newer generations grow up in complete sociotechnical environments that co-evolve.

Levels in each quadrant demonstrate holarchy, which is a “kind of hierarchy wherein each new level transcends the limits of the previous levels” (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010, p. 41). In this type of holarchy, each level inherits the waves of the past and adds new ones of organization and capacity. As a result, each level of depth or complexity is “both a part of a larger structure and a whole structure in and of itself” (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010, p. 41). Levels are additive, and all of them are needed in each quadrant. For instance, the level D-Q (Blue) of structure is necessary for E-R (Orange) of entrepreneurship to operate properly.

Lines of Development

Lines of development describe the distinct capacities needed to address the life conditions (levels) at each quadrant (Cacioppe & Edwards, 2005; Merry, 2009). They are sequentially developed to address increasing levels of depth and complexity. Capacities can unfold in parallel and can continue their development across levels. For instance, in technology-driven societies, we need capacities to interact with them. Regardless of the cultural level of a society (e.g., Blue, Orange, or Green), its technology requires certain capacity from its members from understanding traffic lights to operating a nuclear reactor. As a society evolves from one level to another (e.g., from Orange to Green), technology requires different capacities, such as the ability to develop and maintain intentional communities completely in cyberspace.

Graves stated that an individual or society moves from one level to the next once the existential problems (life conditions) of the current have been solved (Lee, 2009). Lines of development are the capacities needed to solve the problems of a given level. Each level presents a set of problems, which the capacities solve. For instance, we are currently working on solving the overconsumption of natural resources brought by the Orange level. We are doing this through the sustainability capacities (lines of development) available in individuals who have shifted to the Green level. We still need the capacities of Orange to develop better and innovative life capabilities, but we need to temper the tendencies of Orange by paying attention to what it consumes. Orange can be more effective and longer lasting with the infusion of the Green lines of development.

States

States are temporary occurrences of aspects of reality (Wilber, 2011). They can last from a few seconds to months and even years. Weather is an example of a state that changes with the seasons and with atmospheric conditions. States are mutually exclusive and cannot occur concurrently (Wilber, 2011). An area cannot be windy and not be windy at the same time. Even though Wilber defined this construct as part of Integral, it does not have a direct impact to conscious evolution; however, it does relate to life conditions that may have a higher proclivity for evolution. Earlier in this essay, I pointed to the unique state of landmass, temperature stability, and carbon dioxide levels on planet Earth that present ideal conditions for our type of biology to procreate and evolve.

Types

Types are contexts that develop in nature (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). Unlike states, they can be present concurrently. From an integral perspective, types help with the understanding of phenomena manifested in any of the quadrants. As an example, the typology of the Myers‑Briggs’ Type Indicator (MBTI) guides us in the understanding of externalized individual behaviors in the upper-right quadrant. They also help us to see how social systems operate based on the MBTI of the individuals in the system. There are almost an infinite number of types in nature from the physical (e.g., blood type) to the psychological (e.g., personality types).

The Conscious Evolution Holon

This section explores my relationship with conscious evolution. As stated, I am using the quadratic approach of integral theory to frame and explore this understanding. The semantics I use in this section are founded in the literature of the conscious evolution meta-discipline introduced earlier in this essay. Figure 9 presents a holon I develop to focus the exploration into conscious evolution. It has the required four quadrants from integral theory, and I place my understanding at the middle of all quadrants consistent with the quadratic approach.

In this section, I will explore each quadrant starting with a definition and present levels and lines of development for each. In my understanding, these levels and lines correspond to the life conditions and capacities necessary to gain conscious evolution, the fourth generation human identified by Banathy (2000) that, in my estimation, corresponds to the Yellow stage defined by Graves. Wilber has written about the Yellow level of awareness but has not built a complete model for each quadrant. The rest of this essay introduces a complete model for each quadrant with levels and lines of development. There are no concrete and complete examples of holonic models in the integral theory I have surveyed. Consequently, there is no way to validate if the models I am presenting are accurate and faithful to integral theory. However, I believe that building these models has deepened my understanding of conscious evolution. Integral theory aims at a deeper understanding of reality through the interconnected lenses of the four quadrants (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2010). From this perspective, the models in this section have served their purpose.

Figure 9. The conscious evolution holon developed by the author. It is based on the principles of integral theory as addressed in Cacioppe and Edwards (2005); Edwards (2005); Esbjorn-Hargens (2010); and Wilber (1997, 2000, 2011).

Subjective Quadrant

This quadrant corresponds to the “I.” It is the subjective form of experience. This quadrant can only be accessed through the individual’s awareness. It is not visible or accessible to others. The subjective quadrant contains the memories and experiences of the individual. Personal values and morals are its foundation. The main activity in this quadrant is reflecting (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2009). In this subjective reality we learn through experiencing, collecting data, and then reflecting. The operating question for this quadrant is, “What is happening?” Edwards (2005) referred to it as the “illuminative strand” (p. 284).

From a conscious evolution perspective, the subjective quadrant reflects our individual relationship with evolution. It starts with an awareness of the evolutionary process and extends to the notion that we are an integral part of the evolution of the universe and actively participate as co-creators (Merry, 2009). I have to assume that there are even deeper levels of conscious evolution that are outside my own awareness and what is documented in the literature. Even though we understand the evolutionary process in different ways, the purpose of evolution is even more relative (McIntosh, 2012). To some, evolution is accidental, and its purpose is purely mechanical. For others, God controls evolution, and how and why it works remains a mystery. Yet others understand evolution as a grand design emanating from a great intelligence. The meaning of evolution in this manner of understanding comes from its coherence (McIntosh, 2012). A more mystical view of the purpose of evolution involves our own divinity and our journey to integrate with the source of creation. This is a metaphorical reverse “Big Bang” where we journey back to the source of creation, bringing with us the complete understanding of life and evolution.

My own understanding of evolution and its purpose is that all of the different perspectives are possible. At different times in my life, I embraced one philosophy or another. I have held the purely scientific view of evolution as I have embraced a deeply religious conception of why we exist. Through the practice of meditation and self-reflection, I am convinced that evolution also happens internally. Numerous mystics and evolutionary scientists have explored and documented the internality of the evolutionary process. McIntosh (2012) expressed that perhaps a richer set of internal universes are evolving within ourselves with every instant. I believe that I am constantly changing and adapting to new situations and realities. Over the course of my life, I have let go of single ways of knowing and seeking truths that needed to be absolute.

Subjective levels of development

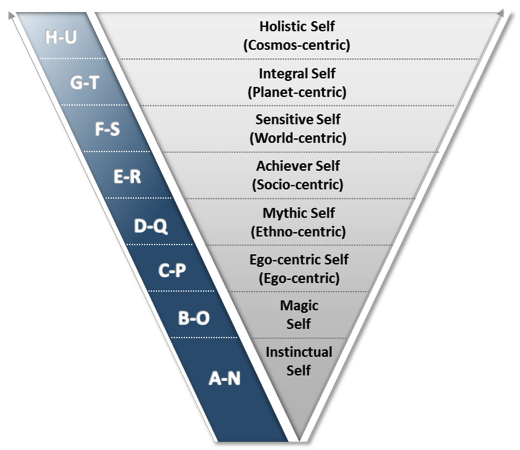

It can be controversial to suggest that we belong to different levels of subjective development. The implications of levels present the notion that a person may be better than another. Merry (2009) explained that developmental levels are more of an expression of directionality of evolution than a given direction. He stated, “Directionality is important because it gives us a sense of our context and the path we are walking” (Merry, 2009, Kindle location 675-678). Merry further suggested that no one can be forced to shift levels and that each of us has our own lessons and tasks in life. Graves’ core research and his eventual development of the ECLET framework were entirely focused on levels of development (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005). Aside from the empirical data he collected, Graves added anthropological details to round up how human consciousness (internality) developed over the last 50,000 years. This time demarcation is relevant because we have archeological evidence to point at an entry point in psychological and social development that our scientific community has followed and documented. Numerous social scientists have addressed levels of development with their own frameworks from Piaget to Lovinger, Kegan, and Graves.

Figure 10. Levels of individual internal development. Adapted from Beck and Cowan (1996).

Beck and Cowan (1996) documented Graves’ research attributing the evolution of self across eight known levels of development (Figure 10). According to these researchers, all humans start at the instinctual level at birth and move across multiple levels into maturity, experiencing the characteristics of each. Levels are part of a holarchy, meaning they are composites of the previous ones. For instance, the achiever self level encompasses the characteristics of the mythic, egocentric, magic, and instinctual selves. Graves found that adults settle on a given level and stay there for most of their lives (Beck & Cowan, 1996; Lee 2009). Levels cannot be skipped and are followed sequentially. Shifting from one level to another constitutes a major undertaking and requires a change in mindset and values (Cowan & Todorovic, 2005, 2008). For instance, a teenager in the egocentric self would require a series of life events and a fair amount of reflection to shift to the mythic self. Typically, with this shift, the teenager becomes a self-reliant young adult interested in a more organized lifestyle with responsibility for self and others.

Beck and Cowan (1996); Merry (2009); McKintosh (2007, 2012); Wilber (1997, 2000, 2011), and others associate the sensitive and integral selves as the state of consciousness needed to be aware of our evolutionary past and actively engaged in the stewardship of our planet. Wilber (2000) was critical of the sensitive self and believes it to be self-absorbed in relative righteousness. This level is post-modernistic and aims to accept diversity in all walks of life. It considers absolutistic thinking as limiting, and modernistic as exploitive. In contrast, the integral self is not concerned with the limitations of any of the levels but rather with the synergies that can be generated by all people at all levels of development. Wilber (2000, 2011) pointed out that true movement in our evolution towards a global community, and world peace and progress, would come when we achieve critical mass at the integral level of development.

My thinking and value system has been aligned with the notion that everything and everyone has a place in the universe. My main mentor in this mindset was my mother. She always had something positive to say about everyone, and I never heard her utter any negativity or even criticism about anyone. Even when challenged by life events and actions directed against her, my mother upheld the goodness in all people and their right to be who they are. She had no awareness of ECLET or any form of levels of evolution. She simply acted in the most considerate manner toward all forms of life. I admired this behavior, and even at an early age I saw it as different than my experience with others. I deeply appreciated my mother’s message of equality and her perspective that no one was in the wrong. I also saw how much empathy she had and how much pain she felt about the suffering of others. She never complained about her own life, just her feelings and hopes for the well-being of others.

I embraced, for the most part, what my mother taught me. I now see how much she operated in the integral way of being. I cannot say that she was concerned about how to make the world a better place but that she was concerned about making the world of those she knew a better one. This has become my primary purpose in life. I do not see any other purpose than to utilize who we are and what we have to make life better for everyone and everything, accepting and respecting all people regardless of their level of development. To me, levels of development are deep perspectives with directionality towards greater empathy and understanding.

Subjective lines of development

There are many potential choices for lines of development. Wilber and other integral theorists provided some guidance on the developmental lines in the subjective quadrant (McIntosh 2007; Wilber 2011). The lines Wilber identified as part of his integral framework include kinesthetic, cognitive, moral, emotional, spiritual, and aesthetic. McIntosh (2007) expanded on Wilber’s work and provided a framework with three broad lines of development: volition, cognition, and emotion. These developmental lines progress concurrently and are impacted by their relationship with the intersubjective reality given that individual growth occurs in the context of interaction with others. (Merry, 2009; McIntosh, 2007, 2011).

Table 5 introduces specific lines of development associated with conscious evolution. This is by no means an exhaustive set; however, it captures subjective attributes amply represented in the conscious evolution literature. It also corresponds to my developmental experience as I became aware of our evolutionary reality and worked to integrate this realization.

Table 5L Subjective Lines of Development for Evolutionary Consciousness

| Line | Definition |

| Evolutionary purpose / agency | Deep understanding of the evolutionary process and our role in it as part of our life’s purpose. |

| Interpersonal / Interconnectedness/communion/ | Knowing and feeling connected to all is brought into awareness and integrated into self |

| Contemplation / spirituality | Need for inner quietness, reflection and contemplation. Development of deeper states of mind. Connection to the global unconscious/the absolute. |

| Beauty, truth and goodness | The value triad that drives our development toward love, gratefulness, wisdom, compassion and empathy. |

McIntosh (2007) emphasized volition as the relationship of self with the universe from the perspective of free will. This agency establishes a relationship both cognitively and emotionally with the evolutionary purpose. Hubbard (2003) identified the purpose of conscious evolution as learning “to be responsible for the ethical guidance of evolution” (p. 360). Laszlo and Laszlo (“Evolutionary Consciousness”) support this notion, stating, “The development of an evolutionary consciousness implies becoming aware of the processes of evolution of which we are a part in order to becoming co-creators of evolutionary pathways” (para. 3). This consciousness strives to guide humanity toward a better future. It also involves the recognition that we are at a critical phase in Earth’s development “in which our old ways of doing things are proving inadequate to the challenges we are facing, and we are searching for more adequate ways of organizing [sic] ourselves that will fit better into our larger context” (Merry, 2009, Kindle locations 823-825).

Csikszentmihalyi (1993) reminded us that our current human life is not the product of planned effort. He posited that planning and designing our future is our central activity for the next millennium. This activity starts with a vision and a concerted direction for evolution. What we should be aiming for, then, “is to facilitate the emergence of a new system by listening to the feedback from the world around us, and from our own inner voices, and by experimenting with ways to adapt” (Merry, 2009, Kindle locations 503-504).

From the interpersonal perspective, Daloz (2000) made the point that we learn through our relationship with the “other.” This is the same concept of Buber’s (1970) “I-You” relationship. Daloz (2000) added that together we are “part of a rhythmic dance of differentiating and integrating” (p. 110), which is central to transformation. This theorist posited that we develop a synergistic consciousness as we gain the capacity to hold different consciousness as equals. He posited that through our own critical reflection on a larger sense of self we can identify “with all people and ultimately with all of life” (p. 105). There cannot be transformation without the presence and influence from the other.

The interpersonal and transpersonal levels are viewed by Buber (1970) as the realms of encounter. This is different than experience. In Buber’s mind, encounter is performed by the person, not the ego. These are also the realms of love and unconditional relating. In Buber’s interpersonal level, we connect to people as if they were ourselves. Love, explained Buber, is when we cannot tell the difference between ourselves and the other person, and we cannot see any fault in the other person. This is also the level of transformation. The “I-You” relationship enables both parties to learn from one another and thus transform. The transpersonal level is where Buber believes we encounter God. This level cannot be reached unless the individual has first learned how to access the “I-You” level through repeated encounters with other persons.

Regardless of religious and cosmological beliefs, spirituality is at the center of our subjective development. It specifies how we relate to the universe in abstract (Merry, 2009). Spirituality defines who we are in the context of evolution and establishes our meaning. Meaning-making of the concrete is learned through our external experiences. Meaning-making with the abstract relies on our inner experience. This experience comes from contemplation and reflection. Spirituality connects us to an absolute reality that cannot be explained, only experienced (Merry 2009).

McIntosh (2007) emphasized that “beauty, truth, and goodness, taken together and understood as an integrated system of primary values, represent a kind of ‘great attractor’ of evolutionary development” (p. 81). He explained that these values form a triad that has been transcendental in our evolutionary psyche. McIntosh further asserted, “The aesthetic, the rational, and the moral, constitute essential, irreducible dimensions of human experience that continually come to the forefront whenever we think about the world from philosophical and spiritual perspectives” (p. 84).

In my mind, beauty is the development of the heart, of our finer emotions. Through beauty, we come to appreciate the universe, evolution, and all of life. Truth is cognition, knowledge, and ultimately wisdom. We learn about our evolutionary reality cognitively, but ultimately we connect with its purpose. Goodness is reflected in all of our actions. At the evolutionary levels, it calls for planetary responsibility. Together, beauty, truth, and goodness are manifested in our compassion, suffering, and empathy (Merry, 2009). Ultimately, we feel and understand how life unfolds and how we connect to everyone and everything. This connection would be impossible without this value triad.

Behaviors Quadrant

The behaviors quadrant contains the objective reality we interact with on a daily basis. Unlike the subjective quadrant, behaviors are perceptible to our five senses, and we can process and make meaning of them. Wilber called it the “It” quadrant (Esbjorn-Hargens, 2009). From an integral theory perspective, the physicality of this quadrant ranges from atoms, to galaxies, suns, planets, life, species, humans, and human behavior. The premise of this quadrant is “acting” (Edwards, 2005). In this form of reality, we learn through physical action and involvement. We perform what is both expected and what we consider to be correct. Ethics are the foundation for our behavior. Edwards (2005) called this the “injunctive strand” (p. 284).

As it relates to conscious evolution, in the behavior quadrant, we practice what we consider to be our role in the evolutionary process. This can range from complete non‑engagement to full dedication to the co-creative process. The latter includes behaviors associated with Banathy’s (2000) fourth generation human. On the one hand, we can act with complete disregard to evolution and its interconnected nature with all of life. Our world’s environmental challenges are the direct result of behaviors disconnected from conscious evolution. As the awareness of the evolutionary process and our role as co-creators emerges and matures, our ethics and actions are in line with environmental conservation, social justice, and the practice of a holistic form or spirituality (Merry, 2009).

My behaviors associated with evolution changed and matured over time. Since early childhood, I remember embracing a deep sense of responsibility towards everything with which I interacted. This included toys, clothing, plants, insects, animals, and all humans. I could not conceive purposely hurting anything or anyone. I always had the sense that everything was alive, regardless of form. To me, even physical objects were relatable and deserved my care and attention. I could not understand why we humans could be so indolent to nature, animals, and each other. Multiple life experiences helped me understand behaviors that hurt others and also me. Making meaning of aggression in any form was difficult and painful. To this day, I react almost irrationally when I witness abuse of any kind.

I did not gain awareness of our planetary condition until I was in my 40s. Since this awareness entered my cognition, I have been an avid participant in social activities that promote environmental consciousness. I am also an activist within my workplace for providing the best working conditions for everyone, including eliminating abusive behavior wherever possible. I know that I can do more as my ethics embrace new life conditions where I can be impactful. I am joyful that through life events and opportunities for inspiring people, I have developed stronger evolutionary behaviors.

Objectified levels of development

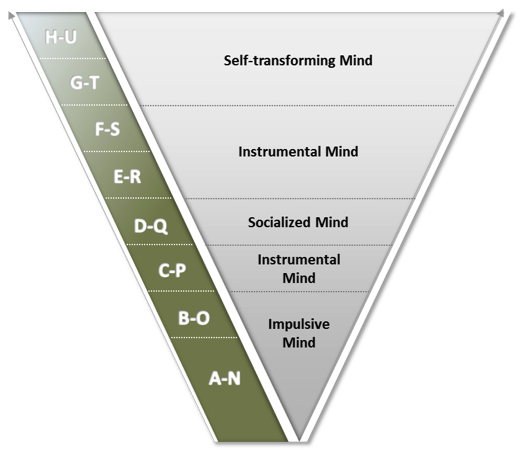

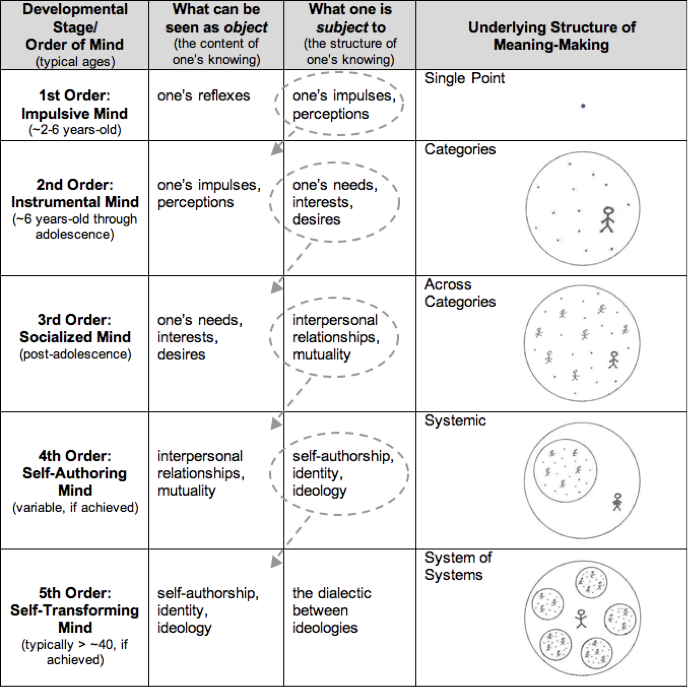

The integral theory literature does not offer levels of development for the behavioral quadrant. Wilber, Edwards, and other integral theorist referred to Wilber’s original documentation on this subject that provides physical levels of development from the atomic to the cognitive brain. It is curious that these theorists referred to this quadrant as the one holding the reality of behaviors. In investigating to develop a complete model for the evolutionary consciousness holon, I kept referring to Kegan’s evolutionary mind framework (Berger, Hasegawa, Hammerman, & Kegan, 2007; Eriksen, 2006; Kegan, 1982, 1994, 2000). Most of what Kegan documents in his framework deals with internal development, but what is attractive about Kegan’s work in this area is that his model has a dialectic correspondence between subject and object. At any level in our evolution, Kegan posited that we have an internal component that is evolving (subject) and one that has evolved (object). When we make the shift to the next level, the subject that we have mastered becomes object and a new subject emerges that needs to be learned (Berger et al., 2007). Figure 11 shows Kegan’s mind development framework.

Figure 11. Kegan’s levels of development adapted and correlated to the eight developmental levels in ECLET (Eriksen, 2006; Wilber, 2011).

In his constructive-developmental theories, Kegan (2000) identified five distinct levels or epistemologies that denote the stages of human internal development. In each level, the subject of the previous one becomes the object of the current. The first two levels deal with reflexes, impulsivity, and the realization of personal experiences. These epistemologies are primary and develop by the time the individual is 20 years old (Eriksen, 2006). The third level corresponds to the socialized mind. This is the level of traditionalism in which the object is concrete; comes from an established point of view; and follows enduring dispositions, needs, and preferences (Kegan, 2000). The fourth order epistemology belongs to the level of the self-authoring mind (Kegan, 2000). The object for this level contains abstractions, the principle of mutuality, interpersonal awareness, inner states, subjectivity, and self-consciousness. This is the level where self-reflection is primary. The fifth order is the level of the self-transforming mind. The object at this level includes abstract system ideology, institution, relationship-regulating forms, self‑authorship, self-regulation, and self-formation (Kegan, 2000). Wilber (2007) introduced an intermediate level between self-authoring and self-transforming that corresponds to the post‑modernistic consciousness that equates to the F-S (Green) level in ECLET.

Table 6: Kegan’s Five Levels of Development and the Correspondence of Object and Subject Relationships Note: Adapted from In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life (Kegan, 1994).

From an evolutionary perspective, Table 6 shows that at the third order of development our behaviors are still concerned with our own needs, personal interests, and desires. Internally, we are developing interpersonal relationship capabilities and the idea of interconnectedness (mutuality). It is at the fourth level—the self-authoring mind—where these mind capacities become objectified and drive our behaviors. The underlying meaning-making structure of the fourth level is systemic, which would be necessary to see how evolution connects everyone and everything. Wilber (2000) postulated a level between the fourth and fifth to place the post‑modern mindset. He believes that Kegan’s fifth order mind corresponds to the integral human who is capable of behaviors aligned with a global mindset that aims to unify and accept full co-creative responsibilities. Table 6 shows the transition to the fifth order mind where self‑authorship, identity, and ideology are in the objective plane and drive behaviors.

A key distinguishing factor in Kegan’s framework for the fifth order level is the conceptualization of all states of thinking as in “both/and” rather than “either/or” of the previous levels (Kegan. 2000). This is a multiframe perspective that is able to hold contradictions between competing belief systems and is capable of accepting the incompleteness of wholeness, that is, the presence of multiple levels of existence as part of a perfect evolutionary process.

Even though my values were based on acceptance and empathy towards everyone, my behaviors were not aligned with my internal development. I remember feeling uncomfortable around certain people and situations. Life events and various mentors were instrumental in shifting my adaptive subjectivity to my external reality. Mutuality-based behaviors took awhile to fully manifest, way into my 30s. I wrestled with what was truly my own interests and desires over the needs and the well-being of others.

It was not until I turned 50 that I felt the beginning of “both/and” thinking being externalized into my behaviors. I experienced the “both/and” thinking for awhile but could not find the language or the form to express it. Over the last several years, I have been more comfortable with behaviors that express a more holistic ideology without any form of dogma. Leaving my dogmas behind was a real struggle. I felt I was becoming empty. I remember a period of at least a year where the consideration of being alive was a real struggle. Then, my thinking became simpler, unencumbered by rules and expectations. My behaviors became more focused and I felt more in control, without trying to be in control. The effort I used to apply to be in control of situations went away, leaving a state of acceptance of everything that occurs as just being perfect.

Objectified lines of development

Integral theory, anchored in Wilber’s work, only offers physical lines of development for the objective quadrant, from the atom to the human brain. It is ironic that this quadrant is the “behavioral,” yet no behaviors along lines of development are provided by the literature. Although McIntosh (2007, 2012) did not provide nonphysical examples for levels and lines of development for the objective quadrant, he delivered an in-depth view on the evolution of the internality of humans, including culture and systems. He posited that science is well aligned and recognizes physical evolution from Lamarck and Darwin to now but that there is significant controversy delineating our nonphysical evolution.

From early age, I had the sense that there were differences in the internal development of individuals and that the person’s age, socioeconomic background, education, and IQ had little to do with how he or she interacted with life and, in particular, others. I was always puzzled by the actions of people in power, assuming that their position bestowed them great wisdom. It was not until I read Hawkins’ (1995) Power vs. Force: The Determinants of Human Behaviour that I became more certain that we humans are at different levels of development. This understanding was further validated and enhanced once I discovered the works of Graves, Kegan, and Wilber.

In selecting the lines of development for the objective quadrant, I chose capacities that are tangibly expressed as behaviors and skills and that are singled out by the leaders in the evolutionary consciousness literature as being relevant to this topic. Table 7 shows the lines of development associated with conscious evolution. It is an amalgamation of my understanding from the conscious evolution meta-discipline and also the behaviors and skills I experienced as I became aware of our evolutionary journey and started to embody its associated responsibilities.

Table 6: Objectified Lines of Development for Conscious Evolution

| Line | Definition |

| Evolutionary learning and competence | Full understanding of evolution, and our place/role in it. Development of evolutionary competencies. |

| Systems thinking | Competency of seeing systems and not just parts. Holistic (not reductionist) approach. |

| Design thinking | Design competency. Applying design principles to social benefit and development. |

| Global ethics | Living values harmonized with global wellbeing |

| Collaborative praxis | Practice collaboration in all aspects of interaction |

| Dialogical inquiry | Development and practice of “thinking together.” |

In her work, Hubbard (2003, 2012) addressed a community that has evolutionary awareness and urges them to learn the history of the universe. Banathy’s (2000) Guided Evolution of Society: A Systems View is a legacy on human and systems evolution and an excellent source for evolutionary learning. Laszlo and Laszlo (“Evolutionary Competence”) have written extensively about evolutionary learning leading to competence. They stated, “Evolutionary competence is about developing the abilities and sensitivities to act upon the awareness and understandings of the two previous stages [consciousness and learning]. The development of evolutionary competence involves self-empowerment as evolutionary systems designers” (Laszlo & Laszlo, “Evolutionary Competence”, para. 2).

To develop competency in any area of endeavor requires practice. Banathy (2000) and Laszlo and Laszlo (“Evolutionary Praxis”) focus competency development on evolutionary systems design. “Conscious competence corresponds to the evolutionary competence stage in which the focus is on gaining mastery of the techniques, skills, competencies, attitudes, and abilities that empower evolutionary systems designers” (Laszlo & Laszlo, “Evolutionary Praxis”). Merry (2009) expressed that “evolutionary leaders are expert learners, continually looking for ways to accelerate their learning and the further development of their consciousness, compassion, and competence to absorb complexity” (Kindle locations 2394-2398).